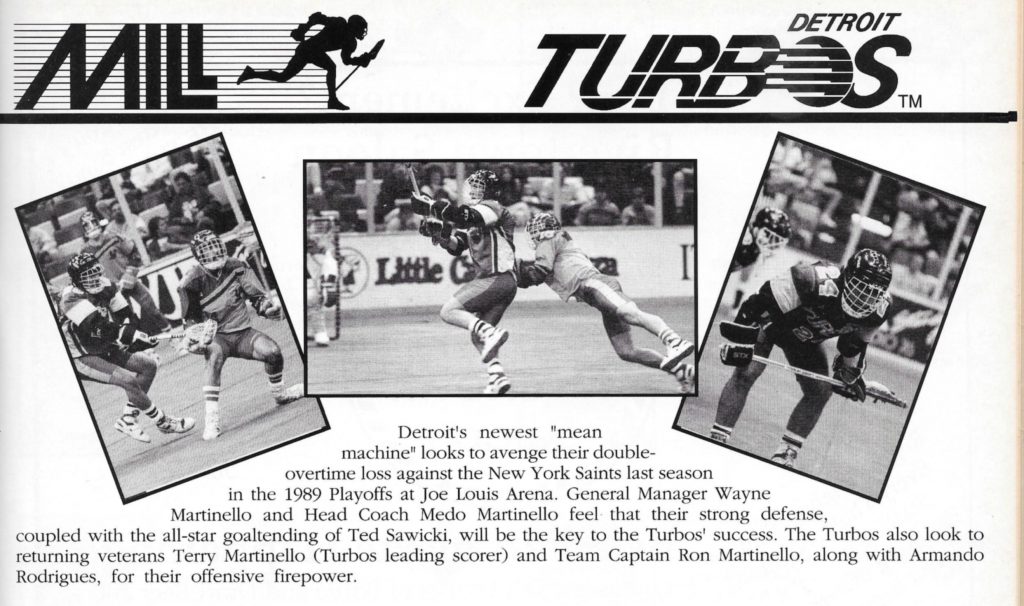

by Stephen Jones: Detroit Free Press Staff Writer, January 5th, 1989

Ask any member of the Detroit Turbos lacrosse team why grown men would let themselves be whacked with sticks for less than $200 a week, and you will get a simple answer.

“I love the game,” said Dan Christ, 23, who played for Birmingham Brother Rice, Michigan State and a Detroit area club team before trying out for Detroit’s newest professional team. “Everyone out here just loves playing the game.”

Passion is important when you’re playing a rugged sport few people recognize in a fledgling league in which player salaries rival the wages of a McDonald’s burger cook.

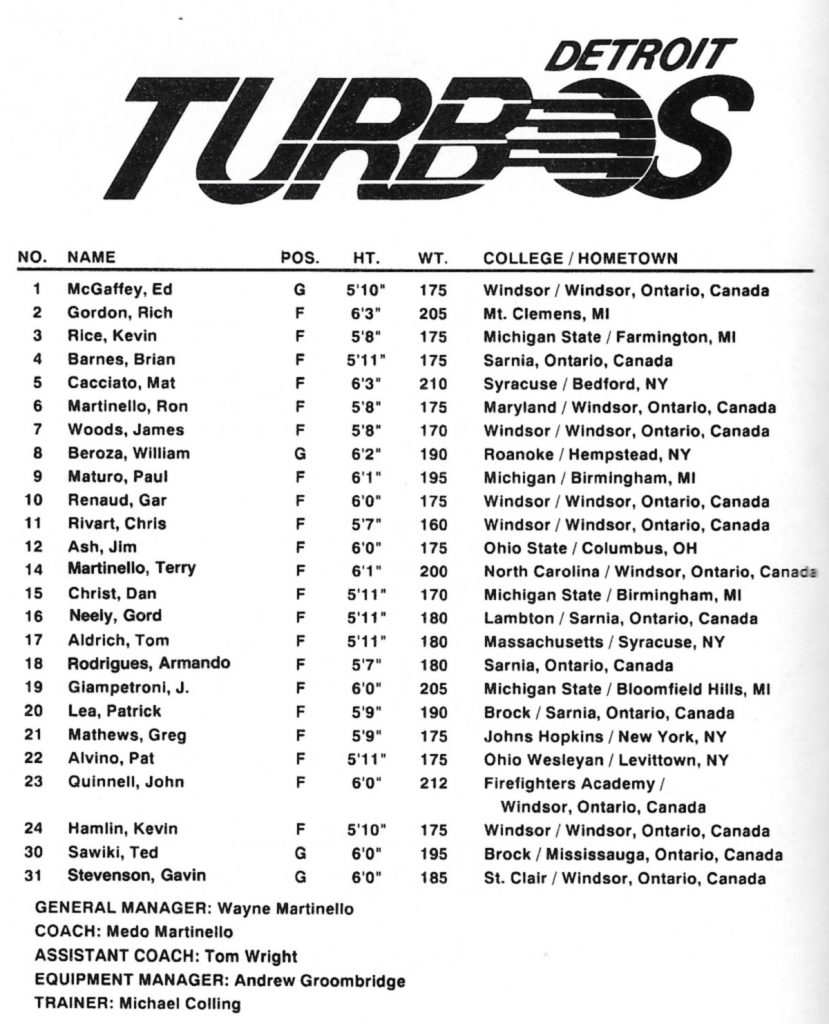

The Turbos open their first season in the Major Indoor Lacrosse League at 8 p.m. Saturday against the Washington Wave at Joe Louis Arena. It’s the third season for the league, which grew this year to six teams from four.

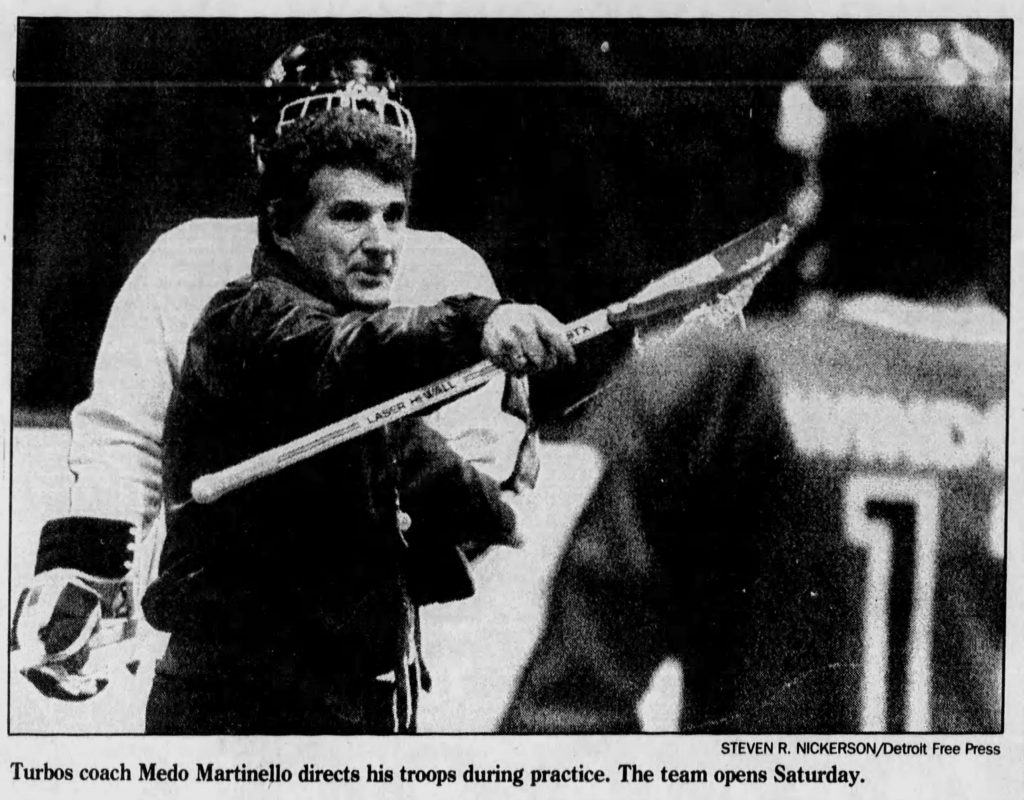

The season is short — four home games and four on the road — but coach Medo Martinello is confident the game will catch on in Detroit.

“I think an eight-game schedule is just enough to whet the people’s appetite so they’ll say, ‘We want it back,’ ” Martinello said. “The game entails the hitting of football, the finesse of basketball and the speed of hockey. Any real sports fan who comes out here and sees the game — they’re just going to take to it like crazy.”

But the sport will take some getting used to for the uninitiated.

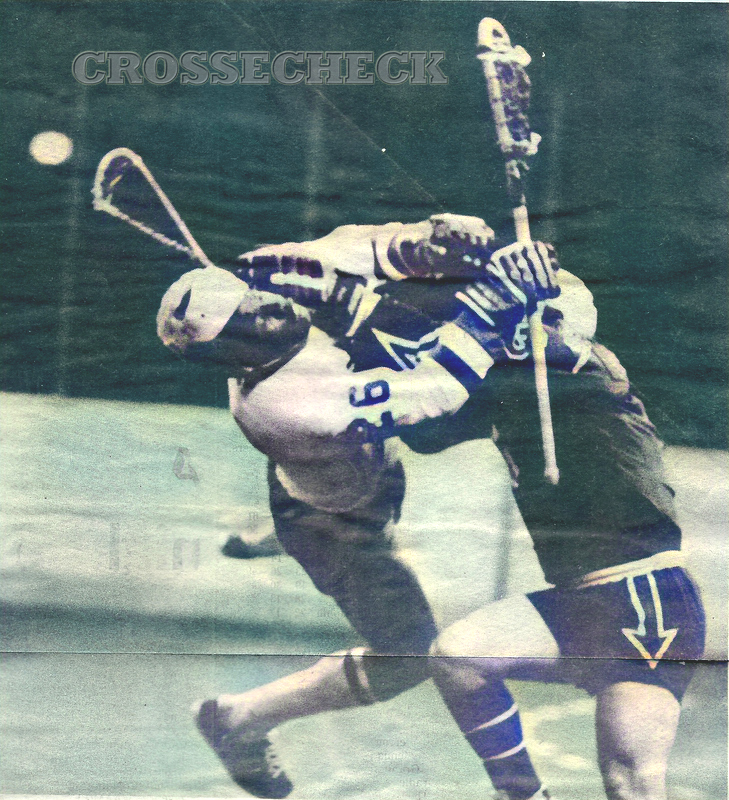

Indoor lacrosse is a fast, rough-and- tumble sport with a lot of body contact. It is most similar to hockey and is played on a hockey rink without the ice. Goals four feet high and four feet wide are set at either end, and each team consists of six players, including a goalie. Body checking and penalties also are similar to hockey, although there are no offsides calls to slow down play and scores are regularly in the teens.

But instead of sliding a puck along the ice, lacrosse players carry a hard- rubber ball in nylon-cord nets at the ends of their sticks. Those sticks give them much more control over the ball than hockey players have over the puck, enabling them to run a pick-and- feed offense that is similar to that in basketball.

“It really is a cross between hockey and basketball, which makes it really fast,” said Gavin Stevenson, a 23-year- old goalie from Windsor who played 12 years in Canadian youth leagues. “You can make a save at one end, pass the ball halfway down the floor and your guy scores. In a matter of five seconds, you’ve made a save and a goal has been scored at the other end. Even in hockey it’s hard to have that.”

Turbos officials are counting on the speed and physical action to turn on fans, and they have some reason to hope. There is a small but devoted audience for lacrosse already in the area. Michigan State and Michigan field outdoor teams, as do a handful of high schools in the suburbs.

An October exhibition between MSU and Johns Hopkins, a traditional NCAA powerhouse, drew 3,000 people to Spartan Stadium in East Lansing. And in Ontario, where the indoor version has long been popular, there are numerous youth lacrosse leagues that may provide fans and future players.

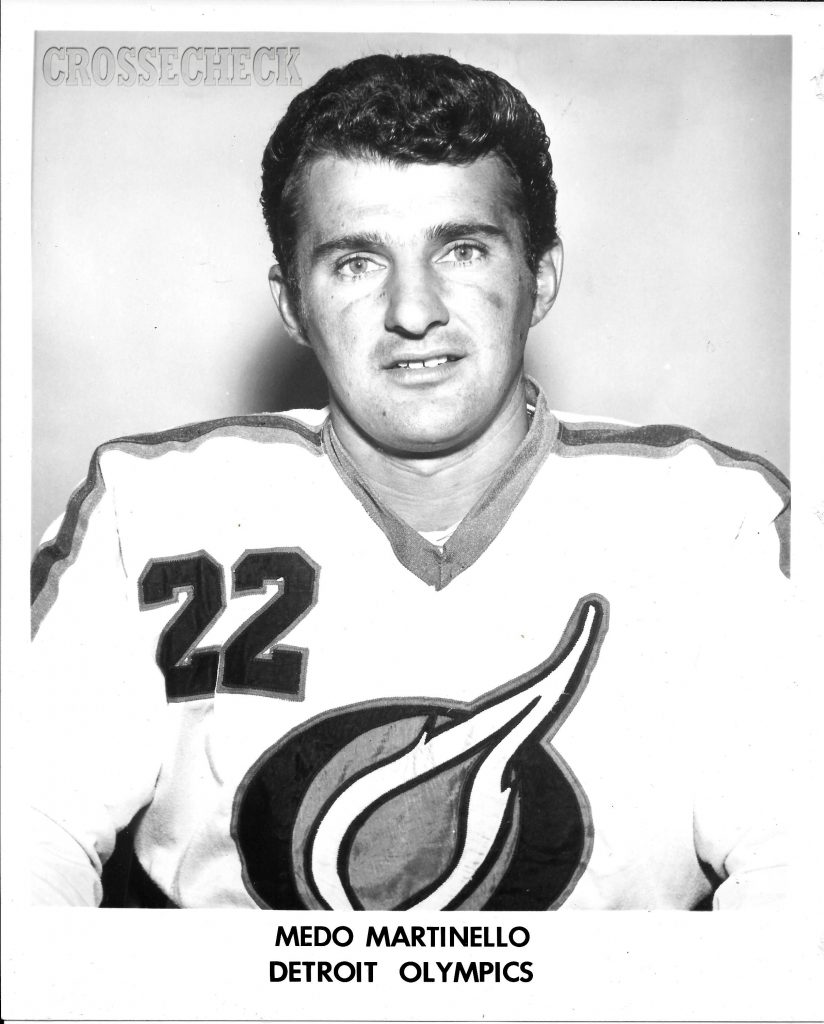

But professional lacrosse has failed once already in Detroit. The Detroit Olympics played one season in 1968 before their league folded. A mid-’70s league that included U.S. and Canadian teams — but none in Detroit — lasted just two years.

Martinello played for the Olympics and coached a Quebec team in the second league. He said the new league was working hard to avoid the mis-takes of the past, such as playing in the summer when fans weren’t interested in indoor sports or offering big salaries to players before the league was established.

Of course, avoiding the latter mistake means the Turbos players — drawn mainly from southeastern Michigan and Ontario — end up playing for little more than their love of the game. But they say that’s all right with them.

“I like the excitement,” said Rich Gordon, 20, of Mt. Clemens, who played at Mt. Clemens L’Anse Creuse. “It’s a good, hard-hitting game. … I just play for the game. I’m not in it for the money.”

And it’s a good thing, too, because life for the Turbos players is about as far as your imagination can take you from the big-bucks, high-profile world of the NBA or the NFL.