By Ray Didinger, Daily News Sports Writer

Philadelphia prides itself in being a tough sports town. A knowledgeable, no-nonsense kind of town.

A hard sell, in other words.

New leagues and new teams usually don’t make it here. Just count the tombstones around Broad and Pattison.

Remember the Philadelphia Bell of the World Football League?

How about the Philadelphia Patriots pro softball team?

Did you catch indoor soccer’s Philadelphia Fever? I didn’t think so.

So how do you explain the Philadelphia Wings?

The local entry in the 2-year-old Major Indoor Lacrosse League doesn’t have any name players, it cannot claim a winning tradition (8-11 overall since 1987), yet the team pulls in big crowds and big bucks whenever it plays at the Spectrum.

Fact: The Wings drew 16,269 (a league record) for their last home game, Jan. 14 against New England.

Fact: They are expecting another big turnout – 13,000 or more, paid – for Sunday’s 1 p.m. matinee with Baltimore.

Fact: They have drawn 110,830 fans in nine home games since 1987. That’s an average of 12,314 per game, double the attendance in the other MILL charter cities: Baltimore, Washington and New York.

The obvious question: Why?

Why has a faceless sport with virtually no Philadelphia roots succeeded where team tennis, women’s pro basketball, minor league hockey, etc., all withered and died?

And why does the MILL thrive here but not in Baltimore and Washington, where college lacrosse is enormously popular? (Almost half of the league’s 120 players come from the Maryland-Virginia breeding ground.)

Two reasons: aggressive action and aggressive marketing by the league, with an emphasis on the latter.

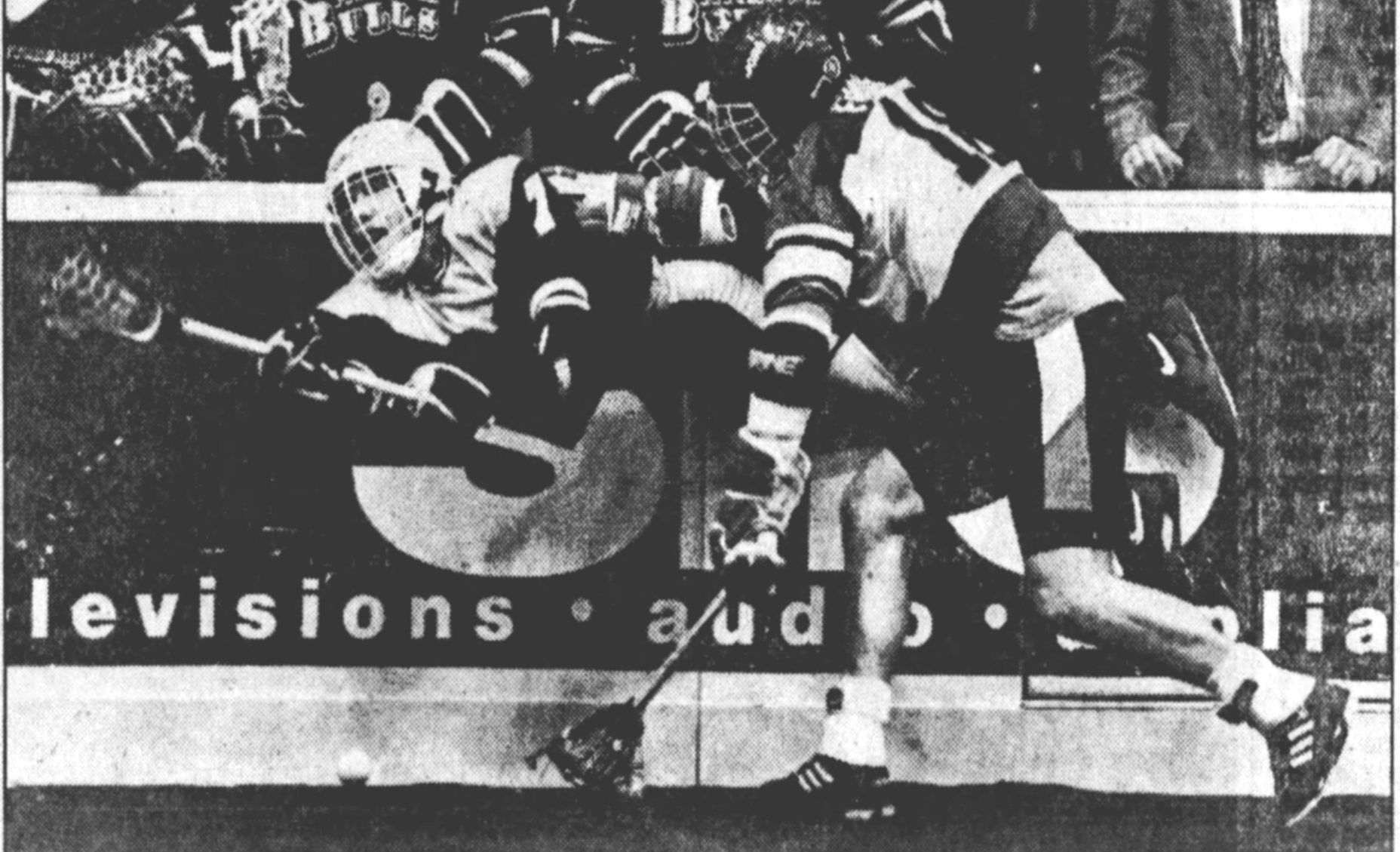

You have seen the Wings’ TV commercials. They sell blood and guts. Slashing, high sticking, crosschecking, bodies crashing against the boards. It is all wham, bam, pow.

The lacrosse people hate it – “It makes the game look like roller derby,” Wings general manager Mike French said – but it sells, especially in Philadelphia.

“As promoters, we have to sell the sizzle,” said Mary Havel, director of administration at MILL headquarters in Kansas City, Mo. “We get some grief from the (lacrosse) purists, but if we had to depend on the purists for support, the league would not have lasted a year. There aren’t enough of them.”

It doesn’t work in every market. The so-called “purists” in Baltimore and Washington are so turned off by the MILL’s rough-and-tumble image that they have stayed away from the indoor game in droves.

The Washington Wave had the league’s best record last season (6-2), but its average attendance at the Capital Centre was a disappointing 7,316. The Baltimore Thunder have fared even worse at the Baltimore Arena.

But in Philadelphia, the MILL successfully has tapped into the same young, predominantly white audience that has grown up following the Flyers.

One theory is that most Wings fans really are hockey fans who can’t afford Flyers tickets. The Wings – with just four home games and season tickets starting at $40 – function as an alternative bandwagon for teenagers and the blue-collar crowd.

But it goes deeper than that. The Wings’ Fan Club has more than 500 members, and it is a real cross section: doctors, salesmen, Cub Scouts, construction workers and housewives. The club filled six chartered buses for the Wings’ Jan. 21 game in Baltimore.

Why such devotion?

“This isn’t like other (pro) sports,” said club president Pat Innamarato, 28, of Rhawnhurst. “These guys play for the love of the game. They give 110 percent all the time.

“It’s so refreshing to see that (effort) in this day and age. I think fans are fed up with these $1 million prima donnas who go through the motions night after night.

“When the game ends, the players sign autographs and pose for pictures. They’re just regular guys with jobs like ours. As a fan, you can relate to them easier than you can a baseball or football player.”

Example: After the Wings’ last home game, captain John Tucker stayed on the floor for 20 minutes, shaking hands. Forward Lou Delligatti, still dripping perspiration, signed autographs and actually thanked the people for asking.

That’s part of the MILL charm. Of course, the fact that the Wings won the game, 19-8, and Tucker splattered several New England forwards against the boards didn’t hurt, either.

The MILL isn’t like the other professional sports leagues. All six teams are owned by Chris Fritz and Russ Cline, Kansas City business partners who promote rock concerts and trade shows when they are not dabbling in lacrosse.

Since all the teams are owned by one corporation rather than individuals, the emphasis is on the overall health of the league. In other words, it doesn’t matter to the home office which team wins the championship. It is more important that all the bills are paid.

That’s both good and bad.

It’s good for the MILL because it does not have to worry about six different owners getting into bidding wars over players. The pay scale is set by the league, along with the travel budget and operating expenses. All revenues go into one pot. One club’s profit wipes out another club’s losses.

“It’s a team effort all the way,” Fritz said.

That’s fine for the owners, but not all the players like it. Several Wings feel the MILL pay scale – $100 a game for a rookie, $150 for a second-year pro, $200 for a third-year pro – is low, ridiculously low.

“These guys (Fritz and Cline) are using us,” Tucker said. “We’re just pieces of meat as far as they’re concerned. We play because we love the game, but there comes a point where you say, ‘Why am I doing this?’ “

Tucker’s frustration is understandable. The last time the Wings played at the Spectrum, the live gate was roughly $190,000. Toss in extras such as program sales, novelties, etc., and it represents a major league haul. The players know that.

So you can imagine how the Wings felt two weeks later when each man had to chip in $30 to pay for the team bus to New York.

The players also pay all their own expenses commuting to and from the weekly practices in suburban Baltimore. (Half the Wings live and work in the Philadelphia area. The others reside in Maryland.)

“The fact is, no one is getting rich off the MILL, and that includes my partner and I,” said Fritz, the league president. “We don’t take a salary. All we’ve done for two years is put out money to get this thing off the ground.

“We lost $300,000 last year. This year, we might break even. The new franchises (Detroit and New England) have done well. Moving the Jersey team from the Meadowlands to Nassau Coliseum was a plus. Of course, Philly has been strong since Day 1.

“What’s happened is the Philly players look at their franchise and think it’s like that everywhere. It’s not. When we were making money in Philly last season, we were losing it in Baltimore and Jersey. We had overhead ($3 million) for insurance, marketing, building costs and operating expenses.

“We’d love to do more for the players,” Fritz said, “but if we go broke, we can’t do anything for them. Right now, we are trying to run the league as sensibly as we can.”

With that in mind, why do the Wings play so hard? Why do they care so much about the game and its fans?

You have to understand these guys aren’t like baseball players; they never looked upon lacrosse as a way to get rich. It was simply a game they enjoyed and played well. Most still play in various outdoor leagues during the summer – for no money and with no one watching.

So the chance to play eight games for $1,600 in front of big, noisy crowds isn’t such a bad deal.

Besides, several Wings use their lacrosse careers to help them in business.

Winger Gary Martin works as a marketing representative for UNISYS in King of Prussia. He has six tickets to every home game and he gives them to prospective clients.

“My biggest customer had never seen a lacrosse game,” said Martin, 27, a former two-time All-America at Penn State. “He had only seen the (TV) ads. He said, ‘You must be crazy.’ I said, ‘Look, just come to one game.’

“He came and loved it. Now he wants tickets for every game and he’s telling other people, ‘Hey, you’ve got to see this.’ It’s a little edge (in business), and every little bit helps.”

The Wings admit it is a struggle. Dave Evans actually loses money by coaching the team. He takes a leave of absence from his regular job – he is a greenskeeper at a golf club near Vancouver – to spend four months in Philadelphia. Evans’s lacrosse salary isn’t much, and his living expenses here whittle it down to almost nothing.

“I’d do better if I stayed home and collected unemployment,” Evans said.

So why does he do it?

“I love the game,” he said, repeating a familiar refrain. “I played it most of my life and I feel like I should give something back.

“My friends think I’m crazy. The first year I did this, they thought it was a novelty. But when I agreed to do it again this year, they said, ‘You must be nuts.’ Maybe I am, I don’t know.”

No one ever accused Mike French of being nuts. The Wings’ GM earned undergraduate and master’s degrees from Cornell. Today, he is a principal partner for the Laventhol and Horwath consulting firm in Philadelphia. Your classic, thirtysomething yuppie.

The only difference is, French’s passion is not BMWs but lacrosse. He was a three-time All-America at Cornell and captained the 1976 squad to the NCAA championship. He played for the Wings in their first MILL season and assumed the management role the following year.

Today, French puts in 16-hour days, juggling his workload at Laventhol and Horwath with his worries about whether the Astroturf carpet will arrive in time for each Wings home game. (The MILL has three carpets and they are shipped from city to city.)

“I just wish I could make more people realize – and appreciate – what’s involved in this league,” French said. “I really get ticked off when people who don’t know anything about us treat us like we’re a circus act.

“To me, the real story of this league is the commitment of the athletes. We’ve got guys who are world-class in their sport, Phi Beta Kappas, car- pooling two hours each way to practice, paying their own tolls. I’ll put their dedication up against any pro in any other sport.

“I think more people are getting the message, at least here,” French said. “I’ve seen our crowds change over the last three years. We’ve got fewer of the beer-guzzling lunatics and more sophisticated fans who appreciate a good game.

“I walk around the (Spectrum) concourse and listen to the conversation. The last game, I heard some fans say, ‘Hey, you know these guys can really play. Did you see that pass? Did you see that shot?’

“I thought to myself, ‘We’re on the right track.’ “

(Philadelphia Daily News, February 9, 1989)