Lacrosse tries for the big time—as violent as ever but faster and with finesse. The Star Weekly’s Jack Batten was there to see them zap that ball, slam that body, load those stretchers, and to report from the front

Lacrosse didn’t die. It merely went into exile, hidden away in small musty centres with sturdy old-fashioned names like Fergus, Coquitlam and Brooklin, waiting for an atmosphere it found congenial to seep into Canadian towns and cities. And inevitably lacrosse’s new day has arrived. A year ago you could spot the cultural signs that heralded its rebirth. Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker cut down by a couple of hundred rounds in the last reel—whoopee! Greasers vs. hippies. The Dirty Dozen. Police brutality. “Burn, baby, burn!” Right, we’re deep in the Age of Violence, and, exactly on cue, the brand-new professional National Lacrosse Association, with teams in six Canadian and two U.S. cities, got under way late this spring, offering a generous sampling from its natural heritage of violent action.

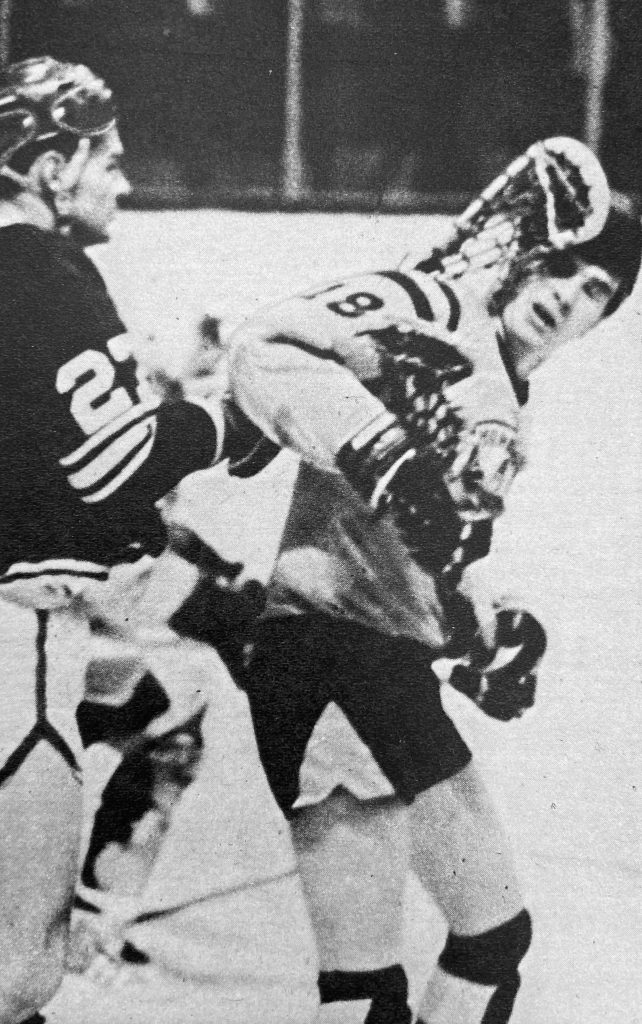

In the seventh league game of the season, one of the two games at Maple Leafe Gardens pictured on these pages, the Toronto Maple Leafs (blue and white uniforms) took on the Peterborough Lakers (green and gold—well, green and yellow) like Doc Holliday and Wyatt Earp up against the Clanton boys at OK Corral. The first period was a relatively sedate feeling-out interlude, marked only by lacrosse’s usual scythe-like stick checking, heavy body slamming and perilous 80-mile-an-hour zapping of the hard-rubber ball. But early in the second period, Peterborough’s Joe Todd was blindsided in front of the Toronto net. He pitched to the floor, both hands clutching his head. Play swept swiftly past his body to the Laker end: Either the referee didn’t spot the punishable rule violation or was adopting the referees’ customary boys-will-be-boys attitude to the game.

Immediately a fist fight broke out in front of the Peterborough goal. This was unusual: Lacrosse players normally hammer each other with their sticks. But fists are almost as effective since in lacrosse, unlike hockey, a player can get a good enough footing on the floor to launch a lethal blow. This thought must have galled one of the Peterborough-Toronto combatants, a large, menacing Laker defenceman named Jim Gooley, who couldn’t seem to nail his smaller, shiftier Toronto opponent. Gooley tried so hard and so long for the KO punch that the referee ejected him from the game, and he left at the same time as poor wounded Joe Todd was being hauled from the arena.

Play resumed with a faceoff to the right of the Peterborough net, and so did the action. The ball ricocheted into the corner. Toronto’s Florrie Tomchyshyn, a squat, bow-legged forward, was first in after it. Tim O’Grady of the Lakers was the second in. Bo-oo-om! O’Grady slammed Tomchyshyn into the boards with as check that almost straightened Tomchyshyn’s legs. He was still unconscious five minutes later when two elderly parties from St. John’s Ambulance wheeled him off on their stretcher. The referee penalized O’Grady two minutes for charging.

By game’s end, there had been 20 minor penalties, three majors, two misconducts, a game misconduct, two fights, half a dozen lesser skirmishes, a cracked jaw (Joe Todd’s) and one severe headache (Florrie Tomchyshyn’s). Just a typical night at the lacrosse matches and the crowd loved it. Oh yeah, for the scorekeepers, the game ended 14-9, Peterborough’s favor.

The men behind the National Lacrosse Association set out from the beginning to capitalize on lacrosse’s appeal to the slightly berserk side of sports fans’ natures. They made their intentions clear in the league prospectus, which they designed primarily to attract potential franchise holders in the United States. “We are living in an age where the public is displaying an uncommon appetite for violence and entertainment,” the prospectus noted correctly—then proceeded to demonstrate how lacrosse satisfied this craving.

But—hooray, or alas—the NLA also recognized that violence isn’t lacrosse’s whole story. “We knew we had the basic product, but we had to dress it up,” Morley Kells explained the other day. Kells is the energetic young coach and general manager of the Toronto team. “What that meant in practical terms was speeding up the game and modernizing it.”

Lacrosse is an ancient game; even in its contemporary trappings, played in air-conditioned palaces like Maple Leaf Gardens [CrosseCheck ed. note: this is incorrect, as the Gardens was not air-conditioned, a fact that would contribute to the demise of not just the NLA team, but also an NLL team six years later], it seems to belong to a world illustrated by C.W. Jeffreys. And in the 1940s it began to show its creaking age seriously. “It turned into a beer drinker’s game,” Morley Kells says, “and it was slow.” Kells conjures up images of portly players with bellies shaped in saloons moving gingerly around the floor flailing maniacally with their sticks. It was mayhem in slow motion. Lacrosse became the only sport whose national championship was won by the team best equipped to cope with a group hangover. One of British Columbia’s good teams of the past, a reasonably swift and graceful bunch, went to pieces whenever they came east for Mann Cup playoffs. How could anyone expect them to handle the double challenge of the championship matches and all those Toronto pubs where rounds of beer were, for these sporting guests, on the house?

To shake lacrosse out of its tipsy and lethargic ways, Kells and his NLA friends introduced a handful of ingenious rule changes calculated to emphasize speed and conditioning. They adapted a 45-second possession rule from a similar regulation in pro basketball—the attacking team must take a shot at its opponent’s net within 45 seconds or give up the ball. They abolished many faceoffs, which were invariably dull, time-consuming affairs, in favor of quicker basketball-style throw-ins. “What we were aiming for was glamor,” Kells says, “and I think we hit it.

The prospect of a glamor game attracted new franchises in Montreal, Detroit and Portland, and existing senior amateur teams in Toronto, Peterborough, New Westminster, Vancouver and Victoria stepped up—or sideways—to the professional level. Amateur teams from Coquitlam and Oshawa made up the nucleus of the Portland and Detroit squads, and the rest of the ranks were filled in a draft of the remaining senior lacrosse players.

Montreal Canadiens encountered the only serious problems in putting a team together. The Quebec Lacrosse Association fired off letter to all the players in the province threatening them with life suspensions from amateur lacrosse if they were caught dickering with the pros. The amateur game does turn-away box office in dozens of Quebec cities where it’s often the only show in town in the summer, and the QLA wasn’t about to abandon its share of the take. Fortunately for Montreal, Ontario took a more sympathetic position. “The professional league is the best thing that’s happened to lacrosse in years,” Brian Higgins, secretary of the OLA, announced. “It’ll give tremendous incentive to kids to play our game.” Ontario helped Montreal stock its team, but Quebec’s intransigence explains why lacrosse’s Canadiens, in untypical Montreal fashion, offer only a single French Canadian name—Michel Blanchard—on a roster notably dominated by Anglo-Saxons.

Montreal’s personnel problems aside, the NLA got off to a running start in April. Running hard and fast, as a matter of fact. “Players were used to working into condition, if they ever made it, in front of the crowds—in games,” Morley Kells says. “But with our new training programs, they were in better shape before the first game this year than they were after the last game in other years.”

The brand of lacrosse these tuned-up, sleeked-down teams are producing bears small resemblance to the old slow game—only the violence remains the same. The NLA has restored tactics, art and mystery to lacrosse. Clever stickhandling is back in vogue. Bullying rushes are out, a faking, feinting, dispydoodle attack is in. Well-drilled offensive teams, notably Peteborough’s, fall naturally into complex weaving patterns around the opponent’s net. Pass, pass, return pass—blink and you miss a move—fake at the goalie, pass off, two players crisscross in front of the net, flick! Score.

The floor has become less a stage for mob scenes, more a platform for consummate all-round performers like Gaylord Powless, the 21-year-old Mohawk Indian who plays, superbly, for the Detroit Olympics. To be sure, the pro game still features such legitimately rowdy lacrosse action as the mass storming of a goalie, the sort of manoeuvre that prompted one lacrosse critic to note in 1940, “Those who have never seen it are not likely to see anything like it, now that calvary charges have been discontinued.” But gradually the dazzling individual efforts of Powless and his peers are beginning to dominate the game.

Powless is a Stan Mikita type. He’s mastered every move—shooting, passing, stickhandling, checking—and he invariably controls the flow and direction of the game with his great sense of tactics. Powless learned his skills under his junior coach, Jim Bishop, in Oshawa, where the Green Gaels won five straight Canadian junior championships, and where Powless set an unmatchable record of 191 points in a single season. The Powless-Bishop team is together again in Detroit, as priceless a union as Rowan and Martin. They sent the Olympics off to the hottest start in the league, five wins before they lost a one-run game to Toronto.

Even the wooly game at Maple Leaf Gardens, the blood-and-thunder affair between Peterborough and Toronto, offered some stunning individual efforts. One of them proved the game’s turning point. Early in the second period with the Lakers hanging on a nervous one-goal lead, 6-5, their talented player-coach Bobby Allan led them down the floor. Allan is a 34-year old phys. ed. teacher who, with his sloping head of pure skin, looks like a younger Bob Stanfield. He handles a lacrosse ball the way Bob Cousy handles a basketball—like a pickpocket. In Toronto’s end, Allan set his team in a purposeful bit of offensive choreography, each man negotiating his own piece of the floor with some intricate footwork, Allan himself at the centre of the pattern. He passed off to his right wing, back to Allan, quick looper to the centre, return to Allan. The Maple Leafs defence, for all their hustling after an interception, grew mesmerized as Peterborough whipped the ball around the Toronto net. Then, precisely timed, in a neat and electrifying motion, Allan faked a pass to his rightwinger and, looking his check in the eye, shot the ball behind his own back in a perfect relay to his leftwinger. The men covering Allan and the left-winger hung like limp puppets. Toronto’s goalie was still watching Allan. The defence was immobilized. Zap. A two-goal lead for the Lakers, and they never lost the momentum Allan’s brilliant play gave them. It was easily the game’s most memorable moment—at least until someone blindsided poor Joe Todd.

(The Star Weekly Magazine, July 13, 1968)