By JOHN BARKHAM

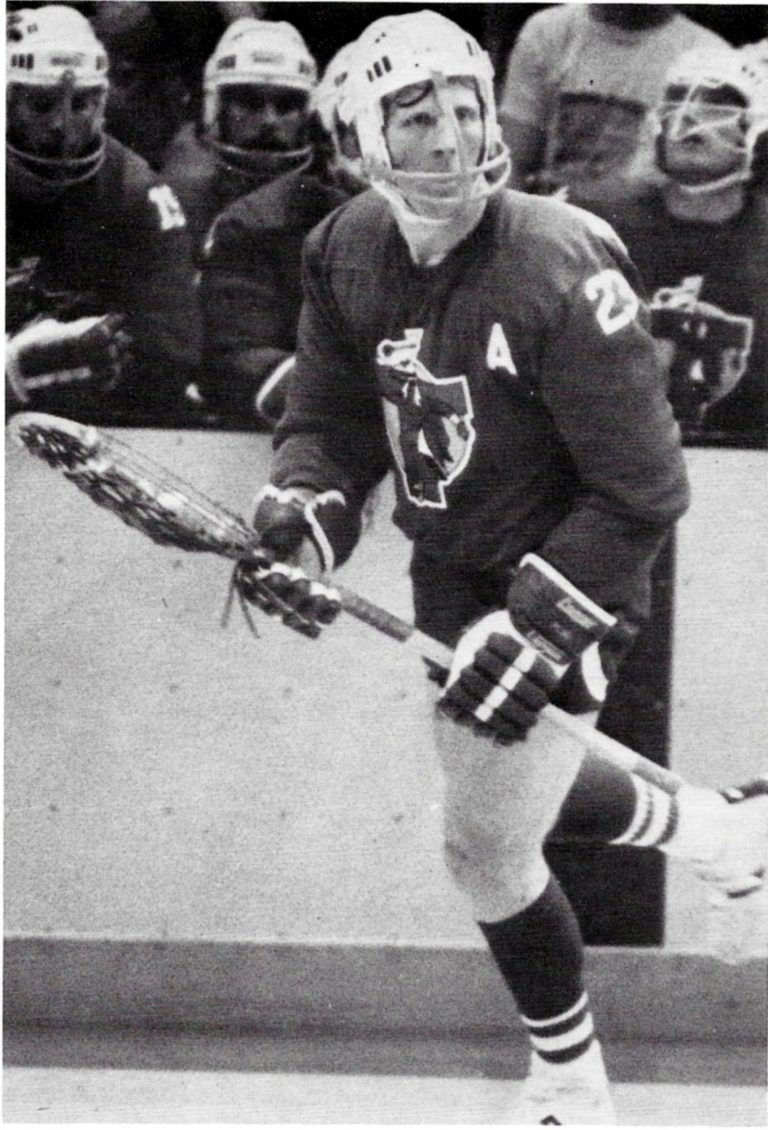

Al Lewthwaite scoring his first goal for the Boston Bolts, against the Quebec Caribous, from 1975

NEW YORK—Box lacrosse is here, offering bits and pieces of hockey, basketball and boxing in a rugged game that stands on the verge of capturing the imagination of sports fans throughout the nation.

In its first few games of the season, the National Lacrosse League has drawn surprisingly strong crowds (including 7,238 on opening night in New York) and is laying claim to the title of roughest sport in the world.

In Maryland, a cartoon character called Attilla the Hun announces from a billboard: “Box lacrosse is the meanest sport in the world.”

Attilla may be right.

Slashing, pushing, tripping, cross-checking and fighting are standard fare in this Canadian summer version of hockey.

Box lacrosse is played in a hockey rink without ice, by six men on a side. The object is to throw a hard rubber ball into the opponent’s net, using sticks with baskets at the end to pass the ball and shoot.

The league itself was born last year in six cities, and currently has franchises in New York, Boston, Montreal, Maryland, Philadelphia and Quebec City.

There is a 30-second shooting clock as in basketball, tackling as in football, and penalties as in hockey. All told, it is an exciting, fastmoving game that is even more violent than hockey.

“But this isn’t hockey,” says John Allen, a 31-year-old forward for the Boston Bolts. “You’re not on skates. You have traction. If a 6-foot-3 guy hits you, you’re going to go down.”

There are penalties, but they are called rarely, seemingly at the whim of the referee.

It is a bruising, demanding and punishing game that developed from Indian roots and was adopted in Canada as a summer substitute for hockey.

Most lacrosse players are Canadian, and they handle their sticks with the skill of a Bobby Orr or a Gil Perrault.

As for strategy, most of it is comparable to basketball, with pick-and-roll, back-door plays and fast breaks figuring as fundamental techniques.

The NLL saw a good thing coming with the hockey boom and decided to capitalize on it with this old Indian game that has never caught the gleam of the public eye.

One of the first things the league did was eliminate most penalty situations to increase the pace of the game,

Fights break out often, and there are regular visitors to the penalty box. One of them is Kevin Parsons, the Long Island Tomahawks answer to Dave Schultz. He says:

“It’s more of a real fight in box lacrosse. You wouldn’t believe how rough it can get, and you’re more liable to get hurt because it’s like street fighting—only a little rougher.”

In Philadelphia, where the rabid fans of the Broad Street Bullies embraced the game in its inaugural season last year, one fan said: “It’s just like hockey, except every team is the Flyers.”

But the violence of the game is controversial not only among parlor sports fans but among the players themselves.

Brian Thompson, a 28-year-old forward for the Boston Bolts doesn’t like the way the league has packaged and promoted the game.

“I hate the way they’re trying to sell box lacrosse to the public,” says Brian, a long-time player. “They’re reducing it to the roller-derby – professional wrestling level when the sport really isn’t that way at all.

“The big slash, crosschecking a guy from behind, piling him into the boards are things that were made illegal 10 years ago in this game because they were very dangerous.

“Last year, they were suddenly legal again.”

Morley Kells, co-founder of the league and coach of the Long Island franchise adds: “It’s a mistake to sell this game totally for its organized war. “Actually, there’s a lot more skill and stamina involved than violence.”

The players, all long-time addicts who have played the game since their youth, are streaming in from even the far-flung Canadian provinces to take a crack at playing the game of their lives professionally.

.

“I’ve been playing this game for 23 years,” explains Davey Wilfong, the Tomahawks’ 27-year-old co-captain.

“Being a professional lacrosse player is something I dreamed about as a kid and now l’m doing it.”

Last year, Wilfong played semi-pro lacrosse and commuted 185 miles to his job as a cop outside Toronto because of it. He made only $85 a game, but he loved every minute of it.

“It was an exhausting grind,” he recalls. “I’d get off the plane at midnight and go work the late shift.

“Sometimes when I couldn’t make it. I’d have to pay guys to work a couple of extra hours for me.”

So the players are dedicated and skilled men who have waited a lifetime for the NLL to come to life.

Many of them quit secure jobs to take a crack at the game, making anywhere between $6,000 and $15,000 a year and waiting for the public to catch on.