by Steve Holroyd (laxmavn@aol.com)

In 1988, the Major Indoor Lacrosse League was finishing its second season, and was well on its way to a third—instantly making it the most successful professional box lacrosse league in American history. Its success was due in no small part to its “single entity” ownership model—instead of franchises being owned individually, the league owned all the teams. Among other things, this helped keep costs down.

Two people were paying attention and decided that, if box lacrosse could do it, why not have a professional field lacrosse league. Terry Wallace and Bruce Meierdiercks were lacrosse teammates at Adelphi University in 1972, and announced the formation of the American Lacrosse League in early 1988.

“Terry and I were All-Americans,” said Meierdiercks, “and we love lacrosse. We’re not doing this for the money. We’re financially sound and in a position to do this for two years,” he added. “Then we plan to sell the franchises to the GMs—at least give them the first right of refusal. Then Terry and I will probably take over an expansion franchise in Philadelphia or Los Angeles or San Francisco.”[i]

Meierdiercks, a New York businessman who sold restaurants in San Francisco, stated that he had thought about establishing a professional lacrosse league since he graduated college, but did not begin to pursue the dream until his father’s passing in 1983. “My father’s death made me realize how mortal we all are. I decided then that I wanted to do all the things that I’ve always thought about doing.”[ii] To that end, Meierdiercks claimed he and Wallace invested $2 million in the league by “pre-paying” two years of expenses. [iii]

Building the league

“This is a pure sport, not a mutation,” crowed Meierdiericks, in a not-so-subtle shot across the MILL’s bow. “Our overhead is very low. We’re leasing small stadiums in suburban neighborhoods and emphasizing family entertainment on Sunday afternoons. We want to get the youth involved through two fan appreciation days, when the players will meet the fans.”[iv]

In a further attempt to get away from the pro wrestling atmosphere that, even then, was permeating box lacrosse games, the ALL stated its games would be played in a family atmosphere. To that end, it decreed that no alcoholic beverages would be sold at games, and that all players would be drug tested. The league said it would need to average 2,500 per game to break even.[v] In keeping with the goal of attracting families, tickets were affordably priced; in Baltimore, for instance, a single game ticket was $8, while a season ticket could be purchased for $56.

The ALL also announced a 10-game cable television package with the FNN/Score Madison Square Garden network, which reached 32 million homes.[vi]

Players were signed to two year contracts, earning $4,000 the first year and $6,000 the second—well in excess of the $100 per game most MILL players were getting at the time. Teams could carry up to 23 players. Riding the “Just Say No” zeitgeist of the era, there were mandatory drug-testing clauses in the standard player contract.[vii]

The first player signed by the league was Greg Fisk, an All-American midfielder from the University of Massachusetts who was assigned to play with the Boston team.[viii]

Notwithstanding the “pure lacrosse” claim, some tweaks to the rules was instituted by the league. A 25-second shot clock was instituted, and only three long poles were permitted (as opposed to the five allowed in college at the time), both rules intended to generate more offense. On-the-fly substitution was also permitted; college rules at the time only allowed substitutions after a whistle. In addition, fast breaks could not be stopped with a penalty; in college, delayed calls were used only in the offensive end of the field.[ix]

The league envisioned a 15-game per team schedule, played on Sundays from April through August. The six teams were: Baltimore Tribe, Boston Militia, New Jersey Arrows, Syracuse Spirit, Long Island Sachems, and Denver Rifles. All but Denver represented traditional lacrosse hotbeds.

Meierdiericks was bullish, and claimed interest in the league was high. In particular, he said he had offers as high as $2 million for franchises, but turned them down because he “didn’t like the people.”[x]

Others also held high hopes for the circuit. Taking note that more than 80 percent of the ALL’s 138 players were All-Americans in college, Baltimore attackman Brooks Sweet gushed “Every game is going to be like Johns Hopkins against Johns Hopkins. I was skeptical at first, but when I saw the caliber of players in the league, I was impressed.”[xi](

The season

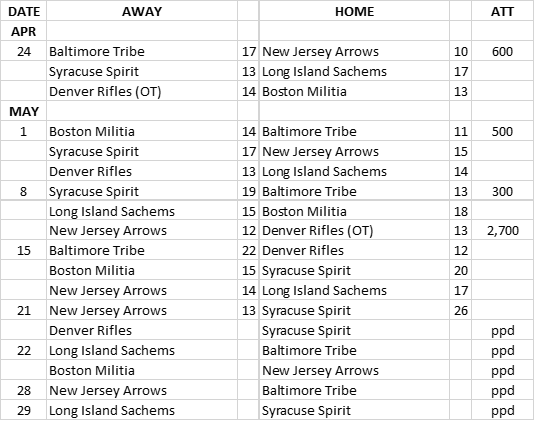

On April 24, 1988, the season opened with all teams participating: Syracuse visited Long Island, Baltimore played in New Jersey, and Boston hosted Denver.

While the quality of play on the field was quite good, the crowds were not: only 600 attended the New Jersey game, and the following week found only 500 attending the first Tribe home game in Baltimore, with the second home game drawing only 300 patrons.

Denver, on the other hand, proved a surprise, with 2,700 seeing the Rifles pull out a 13-12 overtime thriller over New Jersey. Unfortunately for the new league, having a western franchise—no matter how popular—was simply not cost effective, even if, as Wallace claimed, the airline costs to Denver had already been paid in advance.[xii]

By May 19, teams had played four games. However, it was rapidly becoming apparent that Wallace and Meierdiericks had grossly misstated the amount of capital they has invested in the league. Baltimore player checks had bounced on May 16, and the Tribe’s general manager abruptly quit.[xiii] Games were postponed the following weekend, ostensibly to avoid conflicts with NCAA matches. And the Denver Rifles suspended operations, as the team was now accounting for 40% of the league budget, while having sold only six season tickets. “Basically, the financial drain of Denver was such that we had to cut off a finger to save a hand,” Wallace said.[xiv]

That may have been the plan, but gangrene set in shortly thereafter. The slate of games for May 28 was cancelled—ironically, on the eve of the NCAA’s Final Four weekend, the biggest event on the national lacrosse calendar. So sorry was the state of the league at that point that the original plan was to play at least one game in Syracuse, the site of the NCAA final, in the hope of using the money to earn some good will with the players. “If they can draw a decent crowd at Syracuse, they could let the players take the money from the gate,” said Baltimore Tribe coach Frank Mezzanotte. “That would end it [the season] on a positive note, and the league could re-establish itself next year under different management.” Mezzanotte also offered it would take “a miracle, like someone coming forth with $80,000,” to keep the season going.[xv] As it is, even the “charity game” proved to be too much for the league to pull off; on May 27, the plug was pulled on the American Lacrosse League.

Mark Glagola, the second GM in Baltimore’s brief history, summed up the league’s issues:

It was a way [for Wallace and Meierdiericks] to make a buck. I’ll give them credit, they’re great mechanics and set up a beautiful engine. But they lied when they said they had the fuel to run it. They weren’t up front and honest with their financing. They said they had $2 million to carry the league for two years. They don’t. Or else they refuse to put it up.[xvi]

Less charitable was Boston Militia general manager Chris Harvey: “Those guys [Wallace and Meierdiericks] were undercapitalized and blatantly lied to everyone. They claimed they had money to run the league for two years without any fans in the stands. They were unethical and unprofessional.”[xvii]

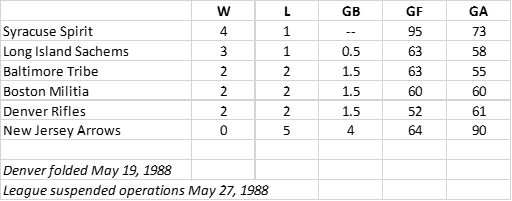

“There’s a lot of disappointment,” said Syracuse Spirit star Jeff Long. “We were really into it.”[xviii] Syracuse was on top of the league at the time the ALL folded, with a 4-1 record. Long Island was in second at 3-1, and Baltimore, Boston and Denver all stood at 2-2. New Jersey brought up the rear at 0-4, including a 26-13 annihilation at the hands of Syracuse on May 21, the last game in league history.

Thus ended field lacrosse’s contribution to the series of “one month wonder” professional leagues that had littered the sport’s landscape since the 1930s.

Although the league is barely remembered today, it did provide a template for Major League Lacrosse to follow 13 years later. In particular, the ALL’s rule changes to generate offense were effective—no team ever scored less than 10 goals in a game—and MLL was quick to incorporate a shot clock and limit the number of long poles when it began play in 2001.

FINAL STANDINGS

FINAL RESULTS

(note:

May 21 game

(the only Saturday match played) apparently cobbled together because NJ had to

postpone 5/22 due to Montclair University commencement ceremonies and Denver’s

ceasing operations)

[i] Tanton, Bill, “Get ready, Baltimore: Here comes another sports team,” Baltimore Evening Sun, April 20, 1988

In 1972, Meierdiericks was a first-team Little All-America defenseman; Wallace was a second-team Little All-America attackman.

[ii] Florida Today, April 22, 1988

[iii] Free, Bill, “’Pure sport’ turning pro with new outdoor league,” Baltimore Sun, April 20, 1988

[iv] Id.

[v] Tanton

[vi] Id.

[vii] Free, “’Pure sport’…”

[viii] Harber, Paul, “Militia march into debut,” Boston Globe, April 22, 1988

[ix] “Professional lacrosse debuts in Syracuse,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, May 15, 1988

[x] Tanton

[xi] Free, Bill, “Tribe takes on New Jersey as pro league starts,” Baltimore Sun, April 24, 1988

[xii] Free, Bill, “Troubles pile up for new pro league,” Baltimore Sun, May 20, 1988

[xiii] Brown, Doug, “Barely a month old, the American Lacrosse League already shows signs of wear,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 20, 1988

[xiv] Burlington Free Press, May 22, 1988 (wire report)

[xv] Brown, Doug, “Signs point to demise of ALL,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 27, 1988

[xvi] Id.

[xvii] Glauber, Bill, “Tribe, rest of league suspend operations,” Baltimore Sun, May 28, 1988

[xviii] “Pro lacrosse league folds,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, June 1, 1988