By Clark DeLeon

“Were you at the game?” asked the bearded man sitting in first class sipping a Bloody Mary on the plane back to Philadelphia from Worcester, Mass., where the homeboys had whupped the New England Blazers 17-9 the night before in the championship game of the Major Indoor Lacrosse League. “Of course, you were there, why else would you be here?” he said, answering his own question.

“I had some business up here Friday,” he continued, sounding like a button-down businessman, even though he was wearing blue jeans and a Philadelphia Wings T-shirt. “My business was to see the BLAZERS get their BUTTS kicked!!”

Meanwhile, back in coach, sat the coach. Victory is sweet, but Wings coach Dave Evans was already worrying about the future. “I hope I have enough money to get my car out of the airport parking lot,” Evans said, pulling a lonely $20 bill from his wallet. And that was only the beginning. “I hope my car starts.”

Evans drives a truly hideous maroon and gray junker of indiscriminate age and modelhood that he bartered from a guy he knows in exchange for six tickets to each Wings home game. It is for such perks that he has left his home and job in Vancouver for six months each of the last three years to coach the Wings, the top team in a league that pays its best players $250 per game and deducts the cost of the bus ride from the airport to the hotel from players’ paychecks.

Why would a man make such sacrifices to coach, let alone play, professional indoor lacrosse?

As with a lot of things in life, if you have to ask, you wouldn’t understand.

The Wings’ fans understand. Philadelphia fans are the most vocal and most supportive of any in the league, and it was really something to see a couple hundred Wings fans outcheer 11,000 Blazers fans at the Centrum in Worcester during the championship game.

When Big Bill Gabrielsen, father of Wings forward Scott Gabrielsen and human semaphore, stood in the aisle behind the Wings bench to form the letters W-I-N-G-S, the Philadelphia fans chanted each letter like it was a game at the Spectrum. In fact, when a New England fan stood up after Gabe’s performance and tried the same thing, the response was so weak you’d think the home crowd didn’t know how to spell Blazers.

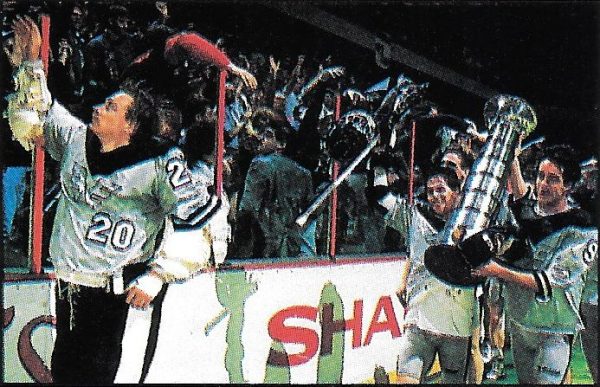

The fans know why. And the players appreciate it. After the Wings won their second league championship, and were presented with the goofy-looking multi-layered erstatz Stanley Cup trophy, the players ran over to a section of the crowd where Philadelphia fans were concentrated and dedicated their victory to them.

And despite the fact that they’re capable of selling out the Spectrum, the Wings remain Not Ready for Prime Time Media Coverage. Until I volunteered to cover the championship game, The Inquirer was prepared to have a stringer from New England report the game. Wings general manager Mike French was so appreciative of having a media entourage (does one man count as an entourage?) accompany the team that he presented me with an autographed team pennant designating my 3-week-old Molly as “the official kid of the 1990-1991 Wings.”

There’s a lot of “kid” in these Wings. I guess that’s why I like them so much. Their joy in being part of the game is so genuine. They are athletes in their prime and they are the best at what they do. So what if the pay stinks? They’d play this game for free, and they do.

In fact, when the plane arrived in Philadelphia there was only one Wings player on board, Chris Flynn, which made for a rather disappointing ”triumpant champions return” shot for the lone TV cameraman from Channel 6 who turned out to record the homecoming. The rest of the players had flown on to Baltimore because they were scheduled to play field lacrosse later that day for their amateur lacrosse clubs.

Flynn, the standout running back for Penn who is a Wings rookie, had the common sense to come home. That’s because his field lacrosse club had a 2 o’clock game at Shipley.

These guys remind me of rugby players. And they accept that as the compliment it is intended to be. They party like rugby players as well. Some of the descriptions of the after-game celebration would make fascinating reading if this weren’t a family newspaper. “How are you going to work the pterodactyl into the column?” Evans asked about a late-night encounter. ”I’ll find a way,” I said. “I’m just wondering how I can describe Delligatti’s bloomers.”

Evans offered to give me a lift home to West Philadelphia on the way to his apartment in Manayunk. It cost him $24 to get his car out of the airport garage (“There goes half my championship bonus”) and the broken hood on his junker bounced comically as he drove on the expressway. “It’s been a slice,” he said when he dropped me off. What the coach needed was some shuteye, but he was headed somewhere else first.

There was a 2 o’clock game at Shipley.

(Philadelphia Inquirer, April 16, 1990)