by Steve Holroyd (laxmavn@aol.com)

Notwithstanding old advertising campaigns that would have you think the sport was played by the likes of Ivan The Terrible and Genghis Kahn when they weren’t raiding and pillaging, it is pretty well established that the sport of box lacrosse—played within boards—was established in 1931. Since then, it has gone on to become one of Canada’s most beloved sports, and is just now starting to make more of a footprint in the United States.

Lacrosse played indoors, however, has been around for much longer. References to “indoor lacrosse” can be found in English newspapers as early as 1887, when London’s Pall Mall Gazette would advertise the game alongside indoor soccer and tug-of-war as being a featured part of national gymnastics competitions. Other references to “indoor lacrosse” can be found in Canadian papers in the 19th Century, but typically when describing winter practices being undertaken by field sides.

Nature abhors a vacuum, however, particularly in the world of sports—and winter in the northeast United States can become pretty tedious, especially in the dense urban areas. Indeed, it was this tedium that prompted a Canadian physical education professor working in Springfield to invent a form of “indoor rugby” in December, 1891 so his students would have something to do in the Massachusetts winter.

The previous winter, however, there was an attempt to make “indoor lacrosse” an established winter game—and, just as important, a spectator sport—in New York City.

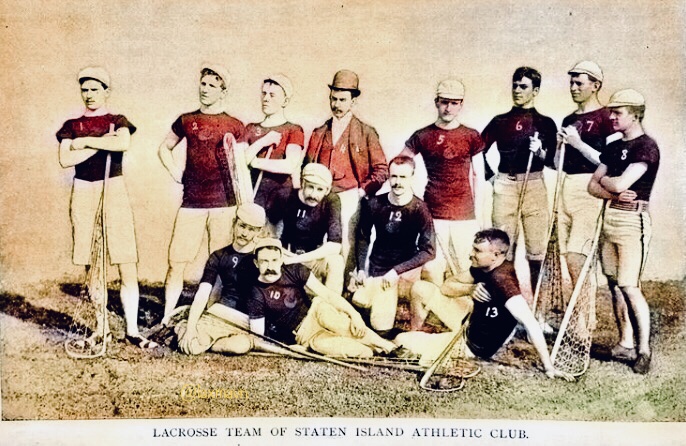

The idea of indoor lacrosse as a bona fide sporting event was pretty much stumbled upon by accident. In December 1890, the Staten Island (NY) Athletic Club hosted a “Great Midwinter Athletic Carnival,” held over three nights in Madison Square Garden. Boxing, wrestling, football, soccer, lawn tennis, and lacrosse were among the events held, and approximately 2,000 people attended the first day’s events, with another 3,500 coming on the second. For a number of reasons, only about 200 individuals attended the “grand matinee” on Saturday, however, and the event was not deemed a success. In particular, the circus atmosphere of the Carnival, with up to a half dozen events being contested simultaneously, was described as “too much Barnum” by the press.

The lone exception was the lacrosse matches, which proved to be very popular. As the New York Herald breathlessly described, in the purple prose of the era:

Talk about the excitement of football or the baby’s first tooth or a panic on the Exchange! They are tame, feeble, colorless events compared with the joyful uproar that lacrosse called out. The Staten Island Athletic Club deserve the thanks of us New Yorkers. They have invented a new winter pastime for our jaded appetites. Indoor lacrosse has come to stay. The club that tries to hold winter games without it in future had better hide itself.[1]

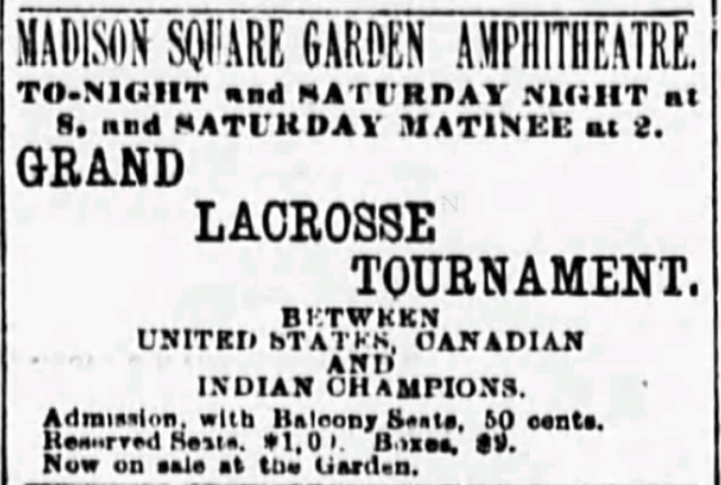

Where there is a buck to be made, strangers will leap in. Early in the New Year, an international lacrosse tournament was announced for January 9 and 10, 1891, again to be held at Madison Square Garden. A wire service report noted:

The lacrosse carnival is in response to a large number of requests. The old Indian sport of lacrosse excited more attention than even football at the recent athletic carnival… The game jumped into popular favor at once. The managers of the Garden have been fairly inundated with letters asking for indoor lacrosse games. No expense has or will be spared to get the best possible exponents of the old time Indian game to participate in the tournament, and entries have been invited from all clubs and players of acknowledged reputation.[2]

Ultimately, six teams were set for the tournament, described in newspaper reports as follows: Montreal (amateur champions of Canada); Caughanwaga Indians (professional champions of Canada); Staten Island A.C. (amateur champions of the United States); the Druids of Baltimore (1889 U.S. amateur champions); Brooklyn (1888 U.S. amateur champions); and Manhattan A.C. Besides the tournament of clubs, the event was to end with an “international” match between “the Canadian champions” and an all-star team made up of the U.S. teams. Given subsequent game reports, it appears Brooklyn and Manhattan were replaced by Jersey City A.C. and Corinthians of N.Y.

As far as the game being played, it clearly was not box lacrosse. Although the coverage of the 1891 tournament does not describe the rules used, it appears “indoor lacrosse” was not merely field lacrosse played under a roof. Game reports do indicate that this was “short-sided” lacrosse: goalie, point, cover point, first defense, center, first attack, outside home, and inside home were the positions, as opposed to a full team of twelve. Also, while no details concerning the Garden tournament were offered in articles about the games, it is pretty likely that the “indoor lacrosse” played in New York was similar to the version that would take hold in Rochester a few years later: regular-sized goals, but with a soft rubber ball instead of the usual solid ball (for the protection of spectators), and games played in 20 minute halves. In other words, “indoor lacrosse” was to the field game what futsal is to soccer today.

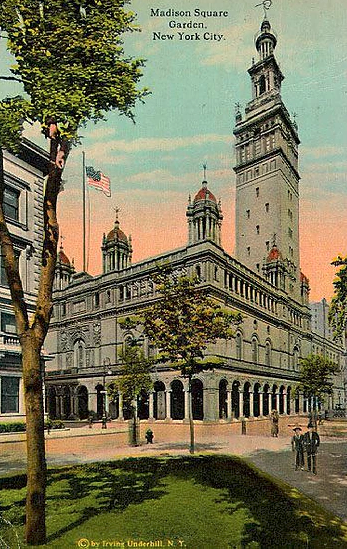

So given all of the excitement, why are we not still talking about the Great Winter Game of Indoor Lacrosse today? Probably because the tournament was a flop at the gate. Only about 800 fans rattled around the Garden—the second building to bear that name was the first to be an indoor facility, located at Eighth Avenue and 50th Street and not yet one year old—which was about a tenth of the seating available.

As far as the tournament, itself, it actually opened with the “international” match: Montreal defeated a U.S. All-Star team, 6-3. The U.S. All-Stars also played the Caughanwangas that day, winning 5-1; the Indians played a second game, losing to Montreal, 3-1.

The Caughanwanga team in 1876 (colorization by RetroLax)

More fans attended the second day, which found a number of exciting games between the participating sides, with the most watched being the game between the two current U.S. champions and the previous year’s title holders, Staten Island and the Druids, which found the Baltimore team winning easily, 7-3. Montreal defeated the Caughanwagas two more times that day, 5-2 and (in an unfinished game), 3-1. In the Indians’ defense, they were probably exhausted: besides playing two games a day, they were also giving snowshoe race exhibitions at halftime and in between the other matches.

Having gone undefeated through the two days, Montreal was declared champions of the tournament.

Unfortunately for those involved, the tournament was not just a financial failure. As playing for pay was still considered less-than-gentlemanly in most athletic circles, there was criticism of the event as a whole:

This tournament is given by the management of the Madison Square Garden Company, not in the interests of amateur sport, not for the pecuniary benefit of any of the athletic clubs, but solely and purely to put dollars into the treasury of the company.[3]

Because of these criticisms, tournament promoters strove to only pair amateur teams against one another; the “professional” Indians were only to be paired against Montreal. However, the Caughanwagas also played the U.S. “all-star” team, made up of amateur players. About a month after the tournament, the Amateur Athletic Union suspended the American players who participated in that game for having played against professionals. Ultimately, all of the offending players—among whom was an astute third year law student named Cy Miller—apologized and promised to abide by the amateur code in the future, and were then reinstated.[4] Between the disappointing gate and a disinterest in dealing with the issues of professionalism, any thought to making indoor lacrosse a permanent “new winter pastime” ended with the tournament. In about 11 months, Dr. James Naismith would invent basketball, and America would soon have a winter sport that could be both played and watched.

Which is not to

say “indoor lacrosse” was dead—a version of the game likely similar to that

played in New York would be played in Rochester in the 1900s, and versions of the

game could be found played in armories in Rochester and Buffalo throughout the

first decade of the 20th Century.

However, and it would be forty years after the Garden tournament before

the thought of staging an indoor lacrosse league—this time, using hockey

boards—would take root.

[1] Montreal Gazette, December 19, 1890 (reprinting New York Herald article)

[2] St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 6, 1891

[3] Fisher, Donald M., Lacrosse: A History of the Game (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), pp. 68-69

[4] Weyland, Alexander M. and Milton R. Roberts, The Lacrosse Story (H.&A. Herman, 1965), p.78

Miller would go on to be a very prominent figure in the development of field lacrosse in the United States, particularly at the collegiate level; in 1932, he was president of the American Box Lacrosse League, the first professional lacrosse league in America. He was inducted into the United States National Lacrosse Hall of Fame in 1957.