by Steve Holroyd (laxmavn@aol.com)

In 1931, the sport of box lacrosse was invented, and was created primarily to fill a specific need: that of hockey arena owners to have a reason to sell tickets after hockey season was over. The International Professional Lacrosse League (“IPLL”), featuring four teams in the cities of Montreal, Toronto, and Cornwall, was largely a failure, and the league collapsed halfway through its second season.

Although all of the IPLL’s teams were from Canada, there was a reason why the league had “International” in its title. Originally, the league was going to include teams from New York and Boston, with the New York team owned by the Yankees baseball owners. Ultimately, the American teams took a pass on the IPLL, and the league was an all-Canadian venture its first season.

It retained the “International” moniker, however, and it hoped that American cities would renew interest in the league in the following year.

Plans for a Canadian-American Loop

On January 7, 1932, plans for the IPLL to expand into the United States were announced by Louis Giffels, manager of the Detroit Olympia. Specifically, it was stated that negotiations were in play to transfer the Cornwall franchise to Boston,[1] while new franchises were planned for Buffalo, Cleveland, Chicago and Detroit. The Olympia and Chicago Stadium were said to be involved in the proposals, but Giffels said that only private interests would back a team in Detroit.[2]

More American cities were reported to have thrown their hats into the ring for the second IPLL season as the New Year progressed: Baltimore, Brooklyn, New York, Philadelphia, Syracuse, and Washington.

Ultimately, however, the IPLL announced on January 30 that only New York and Boston would be added to the three teams that survived the inaugural season (Montreal Canadiens, Montreal Maroons, and Toronto Maple Leafs), along with a second Toronto team (Toronto Tecumsehs). While flattered by the interest, the league determined not to expand too quickly, as “there are said to be not enough A-1 players of the red blooded and redskin game to supply such a demand for teams.”[3]

If the IPLL determined that there was only enough talent to supply two more teams, it made sure to cast its lot with two particularly well-heeled owners. The New York franchise was awarded to Colonel John S. Hammond, President of the New York Rangers of the National Hockey League, and would play in Madison Square Garden. The Boston franchise was awarded to the Madison Square Garden of Boston—later known simply as “Boston Garden”—and would be managed by George Fink. The Cornwall players owned by the league would be distributed to the two teams.[4]

While the franchises were awarded to New York and Boston, it appears that the two cities still had to decide whether they wanted to accept them. It was reported that Hammond and Funk were going to Montreal in early February to make a “first hand study of the game,” and that, “[i]f Col. Hammond’s report is favorable, box lacrosse will make its bow in New York as a spring and fall attraction.”[5]

Apparently, the two Americans were satisfied with what they had learned, as New York and Boston were “definitely accorded franchises” at a special league meeting on February 4.[6] Nevertheless, Hammond and Fink must have had some reservations, as it was reported that:

From early morning until well into the afternoon, terms under which New York and Boston would join [the cities of] Montreal and Toronto in the box lacrosse league were discussed and drawn up. These will be brought before the directories of the United States interests for ratification after which the six-club league will officially come into being.[7]

Interestingly, representatives from Chicago and Buffalo were also at the meeting, perhaps as options if the negotiations with New York and Boston did not bear fruit. By the end of the meeting, however, it was determined that their applications (as well as one from Detroit) were left in abeyance with assurances that they would be given priority consideration in 1933.[8]

In the end, all of the machinations were for naught; the agreements were not ratified by the directors of the two Gardens, and New York and Boston withdrew before the start of the season.[9]

This did not mean that professional box lacrosse would once again not take place in the United States, however. Instead, an entirely separate venture—driven, in part, by some of the men who left the IPLL in the lurch in 1931—would appear south of the Canadian—American border: the American Box Lacrosse League.[10]

Take Me Out To The Box Game

The formation of the IBLL—and, indeed, the creation of box lacrosse itself—was largely driven by owners of arenas, looking to fill the stands during hockey’s off-season; while hockey seasons may end, the requirement to pay rent or mortgages continued all year long. Revenue streams were desired.

Similar motives prompted the owners of five East Coast baseball teams to also consider the viability of professional box lacrosse—but as an outdoor game, played at night and in baseball stadiums.

It should be noted that this would not be the first time that baseball owners ventured into another sporting arena in a desire to fill grandstands that would otherwise sit empty in the off-season. In 1894, six National League teams formed the American League of Professional Football, the first professional soccer league to have formed outside of Great Britain.[11] This was not a successful venture, collapsing about two weeks into the season.[12] In 1901, some individuals involved with the newly-major American League also attempted to establish a professional soccer circuit, but this attempt collapsed before a single game was played.[13]

Even assuming the individuals involved in the ABLL were aware of those earlier failures, they remained undeterred in their intent to bring professional box lacrosse to the United States. While it is easy to understand the desire to do so—money is money—the timing of the venture is nevertheless curious.

For instance, unlike in 1894 and 1901, the owners of these baseball stadiums had off-season options for keeping them in use—namely, professional football.[14] With box lacrosse, these owners hoped to fill stadiums during the only other period they were being underused–in the evenings.

If the desire to squeeze every possible bit of revenue out of these facilities seems a bit piggish, it must be recalled that this venture was starting up in 1932—at the peak of the Great Depression in the United States, with an administration (led by President Herbert Hoover) at a loss as to how to effectively combat it. By that time, attendance for major league baseball games had dropped by 70% from pre-Depression levels.[15] As a result, any additional revenue that could be gleaned from stadiums that were otherwise sitting vacant was welcome.

On March 18, ABLL Vice President Victor K. Ross spoke before a group of interested coaches, officials, and players at the Association of Commerce in Baltimore to unfold plans for the new league. As the box game was still virtually unknown in the Baltimore area, Ross explained that the game called for six men on a team, and “a playing field of approximately 200 by 100 feet, inclosed [sic] by boards four feet high, with a wire screen extending eight feet higher.”[16] Ross further explained that the game was much faster than field lacrosse, as there were no time outs for any cause except serious injury, and the smaller size of the playing field would lead to more frequent body contact. He also stated that games would be played at night, with a schedule of two home games and two away games per week.[17] Another rule change found the traditional draw eliminated, and replaced with the ball being dropped between two facing opponents, similar to ice hockey.[18]

Of more interest was the structure of the league. Ross indicated that the new league was taking advantage of the experience its owners had gathered in professional baseball, and would have players signed by the league and then distributed to teams in such a way as to ensure that no one or two teams would become too dominant. In addition, a salary limit of $20 per game for each player would be imposed.[19]

Much like the IPLL, the American league was not formed because a sporting public was clamoring for box lacrosse; also like the Canadian league, the primary impetus for the ABLL was the desire of its teams’ owners to not have vacant dates on the schedules of arenas they owned. Unlike the first league, however, the ABLL games would be played outdoors, in baseball stadiums, in portable boxes.[20]

The decision to play in baseball stadiums was not just driven by a desire to fill the stands when they might otherwise be empty because the baseball team was not playing. In 1931, IBLL crowds were below expectations, in part because of the miserable conditions fans encountered when sitting in hockey arenas in the summer. Newspapers referred to Toronto’s Arena Gardens and the Montreal Forum as “sticky,” “humid,” and “sweltering.”[21] Thus, it was hoped playing games outdoors would provide for a better fan experience.

In addition, games would be played in the evening. As major league baseball did not play night games until 1935, the decision to have box lacrosse played under the lights is a curious one.[22] Given that lacrosse involves a small, white ball being thrown about at high speeds, it is tempting to surmise that the owners of the ABLL were not just using the league as a revenue stream for their stadiums, but also as a testing ground for the viability of night baseball—in other words, if lacrosse players did not kill themselves while playing under the lights, maybe baseball players would not, either.

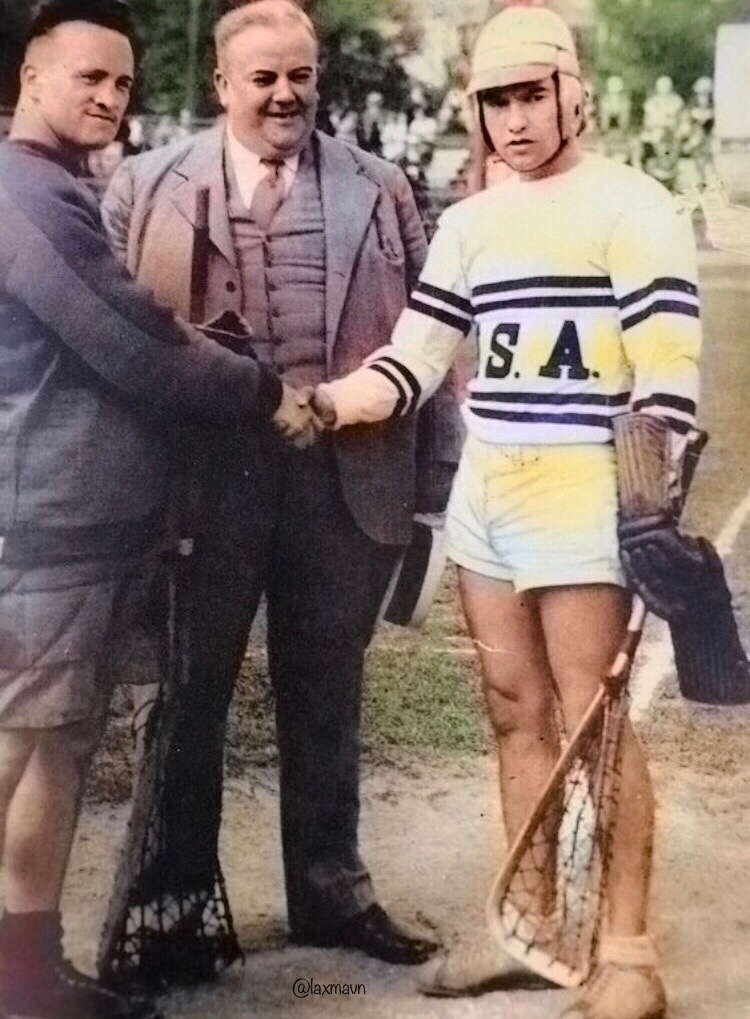

Although the league was primarily driven by individuals who could be fairly described as “baseball men,” there were still some folks well-versed in field lacrosse involved in the venture. One of the biggest proponents of the league was Tommy Burns, operator of the New York Yankees lacrosse team. A native of Hanover, Ontario, Burns (born Noah Brusso) was well-known as a former heavyweight boxing champion, having worn the belt from 1906 to 1908.[23] In his youth, he was a physical field lacrosse player, playing with Galt, Woodstock, and Mount Forest. “Ever since I retired from the ring, I have been yearning to get back into lacrosse,” Burns offered in one interview. “I don’t propose to don a uniform. I think, however, I can show the youngsters a lot of inside stuff that won games back in my days.”[24]

“I think professional lacrosse will make an instant hit,” Burns also said, “because it is always full of action and there is not the exasperating whistle blowing by referees as in ice hockey. Moreover, it is perfectly adapted for play at night under electric lights.”[25]

Burns’ partner with the Yankees—former sportswriter James A. McDonald—was just as enthusiastic, predicting that the new league would be playing to crowds of 30,000 within a year.[26]

The league was formally announced to the public on May 2, 1932, after an organization meeting held at the Hotel Paramount in New York. Officers of the league were introduced: Cyrus C. Miller of the New York Giants, President; Charles R. Bowman of Baltimore, Vice President; James A McDonald of the New York Yankees, Secretary; and Charles F. Aufderhar of the New York Giants, Treasurer. The board of governors was Aufderhar, Miller, Thomas Burns (Yankees), Irving B. Lydecker (Boston), Victor K. Ross (Brooklyn), John R. Norris (Toronto), and Isidor Goldstrom (Baltimore). In addition, it was announced that each team would play 32 home games during the season, while would extend to the middle of September. At the conclusion of the regular season it was planned to stage “a world’s series between the leader of the American Lacrosse League and the outstanding team in England.”[27]

The men who would actually be in charge of the product on the field also began to take shape. In Baltimore, George Bratt, Jr. was named general manager of the Baltimore team.[28]

Baltimore—the lone American city in the league with a deep tradition in field lacrosse—was an important sell for the league:

It took a lot of straining, but it seems that the parties behind the new lacrosse league have sold it to Baltimore.

Reports we get from those familiar [with box lacrosse] have it that it is a pastime filled with action-plus.

Just how it will intrigue the fancy of the customers here is, of course, a question open to debate. However, we are glad that Baltimore is to be included in the American circuit. It sounds like major-league stuff.

Since it will be a nocturnal pastime, it is sincerely hoped they have plenty of paint handy to keep the balls nice and white. It is aplenty hard for the average onlooker to keep track of the ball in lacrosse in the daytime. The box game is far faster.[29]

An Appetizer

Although plans for the league were already on their way, ABLL backers got an early opportunity to gauge interest in the game among New Yorkers; as half the league was based in the Big Apple, enthusiasm among its denizens was key to the circuit’s success. This opportunity came when the New York Institute for the Crippled and Disabled, along with the Cardiac Clinic of New York University announced that a charity box lacrosse exhibition would be played at Madison Square Garden on May 10, between the 1931 IBLL playoff champion Montreal Canadiens and the regular season winner, the Toronto Maple Leafs.

There was genuine interest in this new sport, and it was the topic of a number of opinion pieces by sportswriters. Two common themes quickly emerged—questioning the need to create such a game at all and its exceedingly violent nature. Harold F. Parrott offered an especially cynical view. In a piece entitled “Athletes Must Be ‘Caged’ Now To Get Wild-Eyed Fans’ Fancy,” he wrote:

Box lacrosse will be delivered Tuesday, and the public is expected to tear the lid off with something akin to childish curiosity on Christmas morn, even though the tag reads C.O.D.

Being totally unknown hereabouts, this new “box” game offers nimble-minded press agents the same imaginative possibilities that an unopened parcel at an auction sale would, and many a fancy finger has been wielded on typewriter keys already.

Thus we read on stereotyped sheets: “The new game of box lacrosse had transformed a once lethargic sport that had almost died into a seething cauldron of action. It has become the hardest, fastest, and most thrilling game in the world…”

Uninterrupted action seems to be the sport’s promoter’s dream and the public’s fancy. The fan’s howl and the magnates make wry faces whenever a whistle blows, whether it’s in hockey or basketball.

As a result, the men who are trying to fit lacrosse into a niche in the scheme of big-time sports have taken it off the open field and put it into a net, where the action will be ceaseless because the ball cannot go out of bounds.

Therein lies hockey’s charm—because the dasher around the rink keeps the puck in almost constant circulation.

Therein lies basketball’s biggest woe—too many outside balls. When interest in the court began to wane a few years ago the professionals put the game into a net, where there were no outside balls and the action was continuous. A murderous melee resulted, and they say it isn’t safe to sit in the first three rows around the net when they play this condensed sort of game in Pennsylvania now.

Canada gave hockey to United States fandom and is still crying because it can’t get it back. Canadians scowl and call the popularized version of hockey a desecration of the real game.

Maybe it will be even more so with lacrosse, which is a highly developed game in Canada, though promoters will doubtless often remind a patriotic public in the United States that the game is Indian and American in origin. The box lacrosse bosses have condensed the game in other ways besides putting it in a new and putting a muzzle on the referees. Only seven men play on each team now instead of 12.

Will box lacrosse prove to be the “goods” or only a disappointing parcel? Tuesday will tell.[30]

Also, syndicated columnist Henry McLemore stated in a piece that was distributed nationwide via United Press:

There seems to be a definite trend these days towards bringing all sports indoors where the customers, safe from the elements, may view the proceedings from the comfort of an armchair.

Football, tennis, polo, golf and track, to mention a few, already have been brought in from out of the cold and heat and placed under a roof. And now lacrosse has been placed under shelter. New York will get its first glimpse at box-lacrosse, as the inside game is known, in Madison Square Garden tonight.

With the possible exception of yachting and free ballooning, lacrosse, of all the sports, is the hardest to picture indoors. For this old Indian game of modified murder is normally played on a field about the size of the state of Rhode Island. You need only to see lacrosse as she is played once, to understand perfectly why space, and lots of it, is needed.

When 24 men start swinging hickory-handled butterfly nets around their heads, caring not one whit where the chips may fly, room is a downright necessity. And then, too, it’s sorta nice to have plenty of space so the wounded can crawl off about a mile or two on the side and lick their wounds.

Those who know tell me that box-lacrosse is just like plain old-fashioned lacrosse, only more so. If that’s true it’s plain to see how that box part crept in; the players stand a swell chance of leaving the field of action in one. As in outdoor lacrosse there is a net or cage, and a ball to toss into it for a score. The winner is determined by the number of goals scored. But I am told that those teams which concentrate on knocking opponents and the ball for goals, are rated the highest in public esteem. The perfect box-lacrosser, of course, is one who can knock the ball and an adversary for a goal at the same time.

The game, I understand, is almost as pleasant to listen to as to watch. It seems that the whistling of the racquets through the air (the strings), the cries of the players (the wood winds) and the poom-poom given off by noggins when rapped smartly by the sticks (the drums), create an effect similar to that of a symphony orchestra in full blast.

Incidental noises are furnished by the clang-clang of ambulance bells, the rrr-iii-ppp of antiseptic bandage and the low moans of friends and relatives of the contestants, like a Greek tragic chorus.

Local promoters have reserved several boxes from which to view the game. If it is rough enough there is a good chance that New York will find itself represented in a box-lacrosse league. It is rumored that the promoters, unwilling to trust their own eyesight, have rigged up several devices to record in black and white just how strenuous is the game. One of the devices is a clever little thing that will show the mean average bloodshed per quarter. Another is a sound contraption to record all cries of anguish. And still another photographs and measures the bumps as fast as they appear on the players’ skulls.[31]

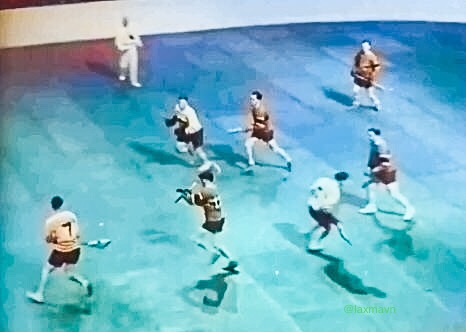

All this build up ultimately drew over 8,000 interested fans to Madison Square Garden, and they were not disappointed. Toronto jumped out to a 3-1 lead after 6 minutes, and held a 4-3 lead after the first 20 minute period. The score was tied 6-6- after two periods, but Montreal pulled away in the third, for a 9-7 win. For all of the hype, there was only one actual fight—early in the game, Joe Smithson of Montreal and Toots White of Toronto went at it after the latter took a swing at the Montreal player with his stick.[32] However, violent contact by way of body checking was in abundance, “causing the crowd to gasp and cheer alternatively.”[33]

American Fans’ Responses to the New Game

ABLL owners were thrilled by the interest in the game.

Casual fans were a bit more skeptical.

Some who attended the game at Madison Square Garden found the sport so violent as to be fake. McLemore, writing for a wire service, indicated he was “a trifle suspicious” of the sport’s roughness, because “no man, living or dead, could have stood up under the pounding some of the boys took.” McLemore also predicted that the league would fold within a month…“in its own blood,” a facetious reference to the supposed violence.[34]

League magnates were not deterred, announcing a 150-game schedule running from June to September.

Building the Teams

While the Canadiens and Maple Leafs had put on a good show, the fact remained that the six teams in the new American league were still starting from scratch.

As the sport of box lacrosse itself was only about a year old, one would have expected the ABLL teams to just get field lacrosse players from wherever to fill rosters. For some reason, however, Canadians were deemed “choice” players and coaches, even with only a one year head start on American players.

Accordingly, in early May there was a flurry or hirings and acquisitions, most from north of the border. The New York Giants announced that Jack Filman had been hired as team manager; the Hamilton, Ontario native had previously coached at Yale. New York Yankees General Manager Joe Boynton announced that his team had hired Andy Russell, from Calgary, to be coach. Baltimore tapped Clem Springs to serve as coach; Springs was familiar to the club because of his role as a coach at the U.S. Naval Academy, but he was probably more attractive to the team by virtue of the fact he had played with Cornwall in the IBLL the previous summer. Boston Shamrocks inked Princeton University head coach Al Neis to lead their side, and Brooklyn was reported to be seeking Percy LeSueur—former Hamilton lacrosse star and NHL goaltender—as its first coach.[35]

Under league rules, players could not be signed until May 19—about one month before the circuit’s opening day on June 17.[36]

The League Debuts

The ABLL began play in June 1932 with six teams: New York Yankees, playing at Yankee Stadium; New York Giants, playing at the Polo Grounds; Brooklyn Dodgers, playing at Ebbets Field; Boston Shamrocks, holding games at Fenway Park; Toronto Maple Leafs, playing at Maple Leaf Stadium;[37] and Baltimore Rough Riders, playing at Oriole Park. As was the plan from the start, all games were played in the evening, under the lights.[38]

The league opened with a splash on June 2, when approximately 10,000 fans went to Yankee Stadium to watch New York defeat Toronto, 11-9.[39] Toronto’s Jack McGill scored the first goal in league history. The next day, about 8,000 fans went to Ebbets Field to watch the Dodgers win their opener, defeating the Yankees, 14-4.

While these opening crowds were respectable, they were still far less than league owners envisioned…and subsequent attendance figures were well below those of the openers. Even Baltimore, stocked with local stars and the most dominant team in the league, could draw only about 3,000 per game.

Within two weeks, the Yankees and Maple Leafs were dropped from the league. Teams from Philadelphia and Atlantic City were considered as replacements; the Atlantic City team would have had to play indoors, however, which was viewed by the league as less than optimal.[40] Ultimately, the ABLL opted instead to continue as a four-team league.

Fans were clearly having trouble embracing the new sport. Again, the perceived gratuitous violence continued to be a distraction. As one particularly cynical columnist noted after viewing the league’s debut tilt:

Box lacrosse is the newest of the college games to be commercialized. We don’t think it will amount to much, either, but then we’ve been wrong before. As one who wouldn’t know a game of box lacrosse from a track meet, we tootled up to the Yankee Stadium the other night—they play it at night, it seems—and watched the New York Yankees play against a team from Toronto. We think it was Toronto, but it may have been Montreal. THAT’S what we think of geography. Anyway, we had been warned that lacrosse was just about the roughest sport this side of a Great War, and we looked for ambulances to be piled kneedeep outside, waiting alertly for the casualties to be rushed forthwith to the operating rooms.

However, there weren’t any real casualties, and we came away with the idea that the game wasn’t nearly as rough as it was dumb. We mean, in football when a man gets hurt it is purely accidental, but lacrosse when a man gets hurt it is because some member of the opposing team has spent the last half hour whamming him with a lacrosse stick, for some reason we weren’t able to figure out in the length of the evening. There certainly doesn’t seem to be much sense to that. Lacrosse is a lot like ice hockey, only they use sticks that look a lot like snowshoes instead of the usual hockey clubs, and the ball is tossed instead of lammed. The idea, as in most games, is to get the ball over the line into the goal box. The Yankees were pretty good at it, too; got it over about a dozen times. When the ball lands in the goal net a little red light flashes, the referee tweets his whistle and eight old grads in the audience cheer.

But the punishment part of lacrosse seems senseless. All of a sudden, for no apparent reason, a whole team will take a dislike to one man on the opposing team and pile on him. The referee will them punish the battling team be sending a couple of its members to the bench for a couple of minutes. When they get back in the game they begin belaboring each other with the sticks again, which is the way it goes, and which isn’t terribly spectacular or thrilling….[41]

One might think that “violence” would still be palatable, as long as there was competition. Alas, it probably did not help that Baltimore was annihilating the remaining three teams. By way of example, the Rough Riders’ final three games had scores of 12-3, 13-7, and 17-10. In 9 games, Baltimore scored 112 goals (41 more than Boston, the next highest team) while yielding only 47 (12 fewer than next-best Brooklyn). Featuring future Hall of Famers John Boucher, Ed Lotz, Phil Lotz, Bobby Pool, Bill Evans, Andy Kirkpatrick, and Averly Blake, the Rough Riders were a team for the ages.[42]

While Baltimore was dominant, the remaining three teams were evenly matched. However, their relegation to also-ran status so early in the campaign was a deterrent—even to fans in Baltimore. “The majority think the competition must be closer. Four teams are not enough and Baltimore is too strong for the other three.”[43] One suggestion:

When Ban Johnson was building the American Baseball League he took the strong players of one team, shifted them around and built up other franchises to make the competition even…Maybe that’s what’s needed in the American Box Lacrosse League.

It might be a good idea to divide the Baltimore squad into three parts, leaving one here, sending another to Atlantic City and a third to Philadelphia…Thus, a six-club league would be developed and Baltimore’s superiority reduced.[44]

Although the skeptical Henry McLemore was joking when he said the league would be defunct in a month, it turned out he was nearly right. On July 8, the league folded. Baltimore was undefeated in 9 games at that point; to make matters worse for the rest of the league, it had also been reported that the team had signed future Canadian Lacrosse Hall of Fame inductee Chuck Davidson to join the already potent attack.[45]

The Rough Riders soldiered on, forming a four-team league in the Baltimore area.[46] It also appears the New York Giants continued through the summer, playing exhibitions against box lacrosse teams that had formed along the Canadian border.

Baltimore also played some exhibitions and, given the fact that lack of competition was one of the reasons the ABLL folded, it is ironic that it lost two exhibition games to a team that was not admitted to the league.

In the summer of 1932, the Atlantic City Americans played a series of games against teams from the United States and Canada in preparation for representing the United States in the 1932 Summer Olympics. Made up exclusively of Native Americans, the Atlantic City side played a dozen games that summer, winning all of them.[47]

Two of those games were against a team called the “Baltimore Orioles,” but made up primarily of Rough Riders. Atlantic City won both games in convincing fashion, 13-6 and 14-5.

While it cannot yet be determined whether the Atlantic City team that was denied entry into the league in mid-June was the Americans, if it was it was a missed opportunity for the league to have some balance. Maybe the league would have survived its inaugural season, re-grouped, and continued through the 1930s and beyond.

Then again, success may have never been a real possibility. As noted, the United States was still deep into the Great Depression in 1932. At a time when even professional baseball was struggling (and a major professional soccer league, the American Soccer League, had just collapsed), starting a new pro league may not have been the best move, as fans did not have the disposal income necessary to allow them to come watch—especially a new sport with which they had no familiarity. Any such money was better spent on “tried and true” baseball.

In just over a month, the ABLL was gone—and it would be another 35 years before professional lacrosse returned to the eastern seaboard.

| FINAL STANDINGS | W | L | Pct. | GF | GA |

| Baltimore Rough Riders | 9 | 0 | 1.000 | 112 | 47 |

| Boston Shamrocks | 5 | 5 | 0.500 | 75 | 70 |

| Brooklyn Dodgers | 4 | 4 | 0.500 | 61 | 59 |

| New York Giants | 2 | 5 | 0.286 | 62 | 70 |

| New York Yankees* | 1 | 4 | 0.200 | 28 | 73 |

| Toronto Maple Leafs* | 0 | 3 | 0.000 | 21 | 40 |

| *–dropped from league June 16 | |||||

| league disbanded July 8 |

[1] The management of the Cornwall Colts team had sold the franchise and the rights to its players back to the league in December, 1931, claiming that the league’s intention to expand into the U.S. made remaining in the league cost prohibitive. Fisher, Donald, “ ‘Splendid But Undesirable Isolation’: Recasting Canada’s National Game as Box Lacrosse,” Sports History Review, 2005, p. 123; Cornwall Freeholder 12/12/31

[2] Lafayette (IN) Journal and Courier, January 8, 1932

[3] Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, January 30, 1932

[4] Detroit Free Press, January 31, 1932.

[5] Montreal Gazette, February 4, 1932

[6] Montreal Gazette, February 5, 1932

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Fisher, Donald, “ ‘Splendid But Undesirable Isolation’: Recasting Canada’s National Game as Box Lacrosse,” Sports History Review, 2005, p. 125—see also Cornwall Freeholder 12/12/31; Toronto Mail and Empire 8/28/31, 9/19/31

[10] Press reports referred to the league as “American Lacrosse League,” “American Professional Lacrosse League,” and “American Box Lacrosse League.” Ultimately, the last reference was the one most frequently used.

[11] Actually, at the same time the American League of Professional Football (“ALPF”) was formed, there was another group announced as a professional league—the American Association of Professional Football Clubs (“AAPF”). However, there is some question as to whether the AAPF was an actual league, or simply an ad hoc tournament by several existing teams unwilling to cede the professional landscape to interlopers from the world of baseball. In any event, the AAPF appears to have quietly disappeared after the demise of the ALPF. For more on the crazy fall of 1894, see Farnsworth, Ed, “Philadelphia and the Other First Professional Soccer League in the U.S.,” Society for American Soccer History, http://www.ussoccerhistory.org/philadelphia-and-the-other-first-professional-soccer-league-in-the-u-s/

[12] Holroyd, Steve, “The American League of Professional Football, 1894,” Soccer History, Issue 14, Spring 2006

[13] Wangerin, David, Soccer In A Football World (Temple University Press, 2008), p. 96

[14] In 1932, the New York Giants (Polo Grounds) and Brooklyn Dodgers (Ebbets Field) of the NFL were playing in their respective stadiums; in 1933, the Boston Redskins would begin using Fenway Park for its NFL games. Yankee Stadium hosted college football teams; it was also the site of the Army Navy Game in 1930 and 1931, but the game would move to Philadelphia—on a largely permanent basis—in 1932.

[15] Vorel, Lauren M. (2010) “The Great Depression: Catalyst for Change in America’s Game,” Constructing the Past: Vol. 11 : Iss. 1 , Article 6 at p. 41

[16] Baltimore Sun, March 19, 1932

[17] Id.

[18] Baltimore Sun, May 10, 1932

[19] Id. $20 is the equivalent of approximately $357 in 2018 dollars (https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm).

[20] “Portable Box to Be Set Up For Lacrosse Work At Oriole Park,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 27, 1932.

[21] Fisher article at 121

[22] The first night game in the history of major league baseball occurred on May 24, 1935, at Crosley Field in Cincinnati. However, the temptation to play baseball under the lights arrived almost immediately after the invention of the light bulb; an experimental game between two department store teams took place as early as 1880, one year after the invention of the light bulb. By 1930, the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues and various minor league teams were playing under lights with some regularity.

[23] Burns is perhaps best remembered as the only white heavyweight champion of the era willing to give Jack Johnson, an African-American, a shot at winning the title. The two fought on December 26, 1908, in Sydney, Australia. Johnson won the title after police—fearing a riot if a black man knocked out a white, which Johnson was on the verge of doing—ended the fight after 14 rounds. Highlights of this historic bout can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oZ_Dguh9hEE

Burns remains the only native-born Canadian to be heavyweight champion.

[24] Ottawa Journal, April 23, 1932

Burns may be overstating his ability as a lacrosse player, however. In 1909, shortly after being dethroned by Johnson, Burns was persuaded to suit up for Vancouver in a match against New Westminster Salmonbellies. “One of the [Salmonbellies] swing his trusty stick, and knocked Tommy cold, and that terminated the latter’s lacrosse career.” Weyland, Alexander & Milton Roberts, The Lacrosse Story (H&A Herman, 1965), p. 50

[25] Philadelphia Inquirer, April 24, 1932. Burns also stated he was looking for Philadelphia investors to add a team to the league, playing at Shibe Park.

[26] St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 2, 1932. (Obviously, this is a recycled wire service article, as the league had folded by the time this remark was published.)

[27] New York Times, May 2, 1932

[28] Baltimore Evening Sun, May 2, 1932

[29] Baltimore Sun, May 5, 1932

The reference to “major-league stuff” is significant. In 1932, Baltimore did not have a major league baseball team, and was still chafing over the loss of its American League franchise after the 1902 season. Previously, it had lost its National League team—which won the pennant on three consecutive occasions (1894-96)—in 1899. It also had a team in the failed attempt at a third major league, the Federal League, in 1914-15. Baltimore suffered from an inferiority complex as a result of not having a major league baseball team (it would not get a pro football team until 1947, the original Baltimore Colts (which folded in 1950 and was replaced with an expansion team of the same name in 1953)); in 1954, Baltimore returned to major league baseball when the St. Louis Browns were purchased and relocated to the Charm City.

[30] Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 9, 1932

The reference to putting basketball “into a net” may be lost on modern readers–at the time, basketball courts were encircled by nets or, in some instances, fences. Hence the coining of the term “cagers” to refer to basketball players, which is still in use today.

[31] Lincoln Journal Star, May 10, 1932

[32] This incident, along with other highlights, was captured by British Pathé for a newsreel. The footage can be viewed here.

[33] Nichols, Joseph C., “Maple Leafs Lose To Montreal Team,” New York Times, May 11, 1932. Interestingly, Nichols states this was a regular IBLL match.

[34] McLenore, Henry, “Expert Foresees Failure For Box Lacrosse League,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 30, 1932

[35] Montreal Gazette, May 4, 1932

[36] Id.

[37] This was not the same Maple Leafs team that played in the exhibition at Madison Square Garden. In that era, it was not uncommon for teams from the same city to share the same nickname: in Toronto, for example, “Maple Leafs” applied to an NHL team, an IPLL box lacrosse team, the ABLL team, and the minor league baseball team backing that team. New York, at various times, had professional baseball, football, and soccer teams called either “Yankees” or “Giants” in the 1920s and 1930s.

Presumably, the habit took hold because fans were used to various sports teams from the same college sharing nicknames. In any event, with the rise in revenue gleaned from sports apparel and memorabilia merchandising in the late 1980s, teams are much more vigilant about enforcing trademarks; as a result, one is not likely to find teams from the same city sharing nicknames again any time soon.

[38] No game reports indicate one way or the other whether playing under the lights was an impediment; indeed, as Major League Baseball would introduce night games three years later, one may assume the experiment was a success.

Of interest, however, is a comment on night box lacrosse (played indoors) from April 1932. The Parkdale Lacrosse Club of Ontario staged several practices under the lights of the Ottawa Auditorium. It was reported that the players, “in their first drill under the electric lights, found it difficult following the ball and it is thought the lighting will have to be improved in order to stage games at night.” Ottawa Journal, April 19, 1932

[39] Jones Jr., Arthur F.“Box Lacrosse Starts; Yanks Halt Toronto,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 3, 1932. It should be noted that Jones’ crowd figure may be wildly optimistic; other reports state only 4,000 attended the opener. See “Last Period Drive Subdues Toronto,” New York Times, June 3, 1932

[40] Baltimore Evening Sun, June 17, 1932

[41] Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 8, 1932

[42] Notwithstanding the league’s earlier pronouncement that it would be responsible for signing players and distribute them equally among the teams, it appears this approach was quickly abandoned. Given Baltimore’s deep field lacrosse tradition, it is not surprising to see the Rough Riders were able to compile such a formidable squad.

[43] “Fans Want Skillful Play,” Baltimore Evening Sun, June 28, 1932

[44] “Speaking of Box Lacrosse,” Baltimore Evening Sun, June 25, 1932

[45] “Davidson May Join Rough Rider Team,” Baltimore Evening Sun, June 29, 1932

[46] “Box league Disbands; Form Muny Loop,” Baltimore Evening Sun, July 9, 1932

[47] See http://wampsbibleoflacrosse.com/newstats/Atlantic-City.txt (retrieved November 5, 2019)