Area’s newest pro team looking for recognition, respect from sports fans

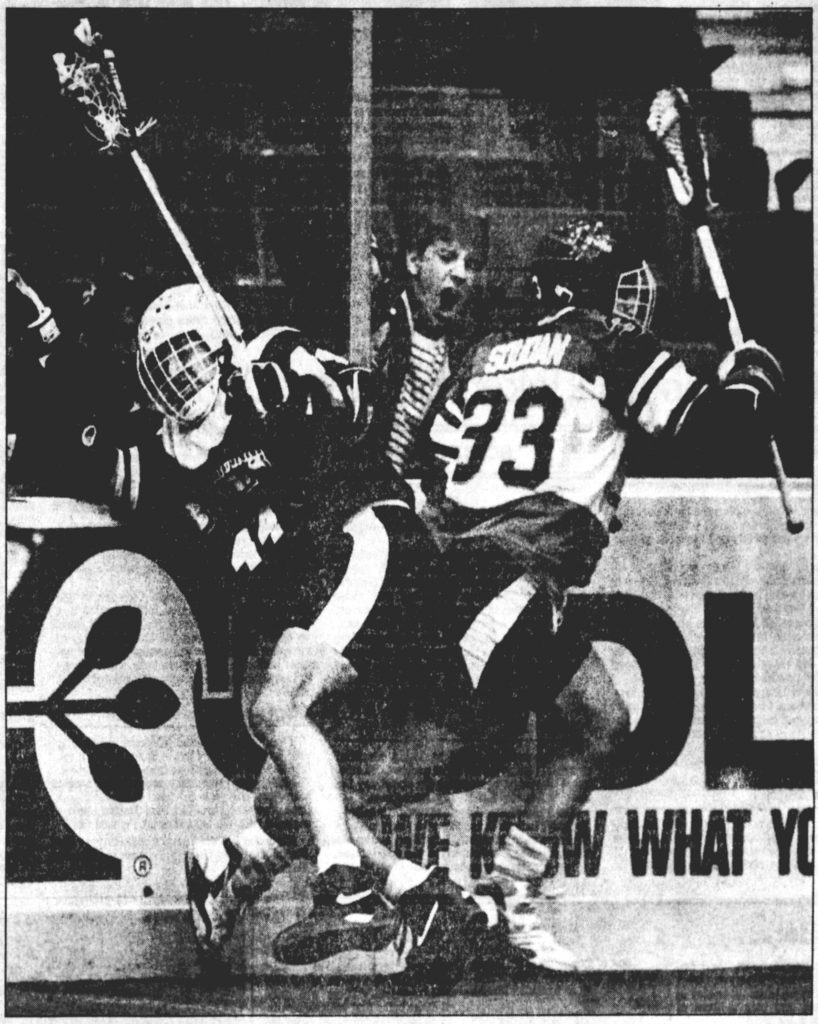

Tim Hormes of Pittsburgh battles Randy Fraser of Boston in game action from the Civic Arena

WHENEVER the Pittsburgh Bulls face off against a Major Indoor Lacrosse League opponent, they are struggling as much for acceptance and respect as they are for a victory.

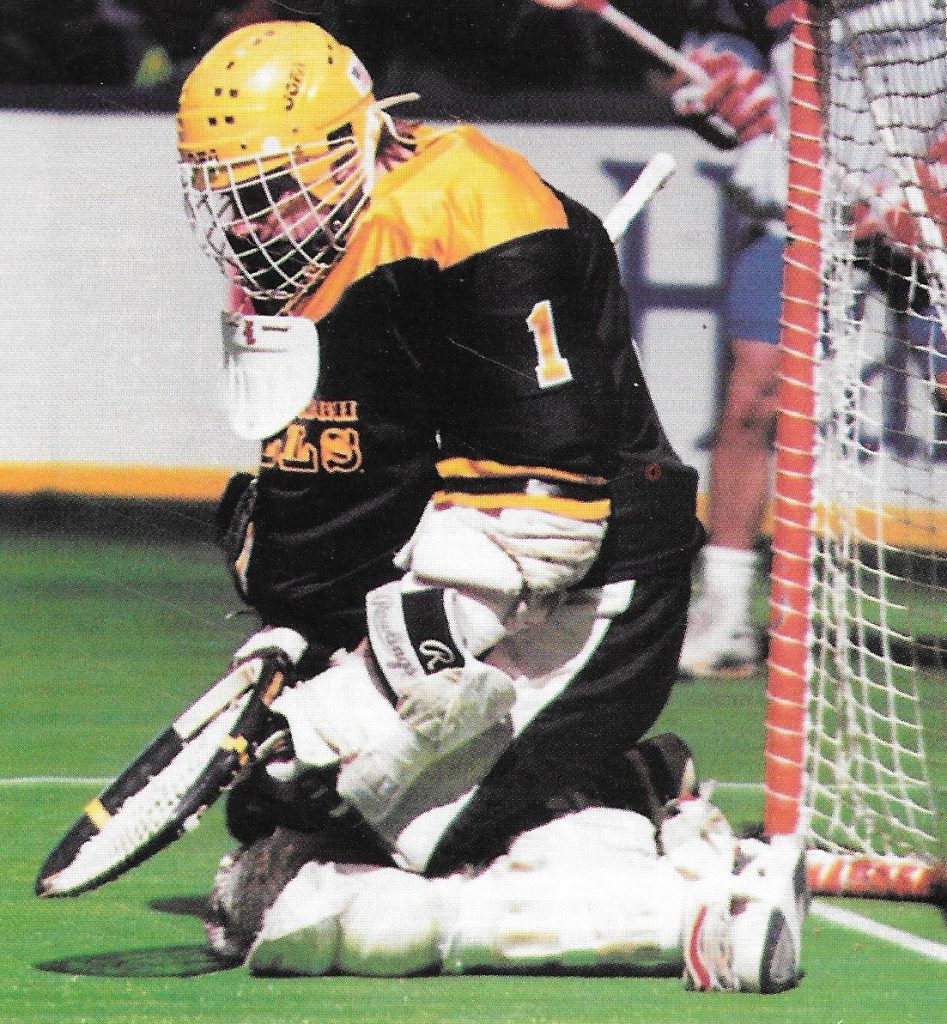

Indoor lacrosse has developed a reputation as hard-hitting and practically violent, which has attracted fans as well as detractors. The Bulls players say the physical play is as integral to lacrosse as it is to hockey or football.

At the same time, the Bulls team members are trying to demonstrate they are more than just hard-hitting goons in shorts, shoulder pads and helmets. Finesse, skill and speed are critical in their game, and they want the world to know about it.

“We’re trying to introduce the sport of lacrosse,” said Bulls forward Joe Gold. “I feel like a pioneer in some ways. I feel like I’m on a mission to expand the sport.” “We are the pioneers of a potentially successful league,” said Bulls forward Butch Marino.

But, like other pioneers, the Bulls face many obstacles. One of the most basic is monetary. The Bulls rank with the best lacrosse players in the country and nearly all came out of successful college programs, but now they’re earning between $1,250 and $3,000 apiece for the 10- game season, based on seniority. Rookies, for instance, have a base salary of $125 per game. Nearly all the Bulls support themselves with other full-time jobs — in software programming, marketing, coaching, landscape design and so forth.

“It feels more like a professional hobby,” said Marino, who works as a sales representative for a medical/pharmaceutical company. “Until the bucks are paid, I don’t refer to myself as a professional athlete.”

The Bulls would like to be paid more, yet money is not their bottom line. “I just love the sport,” said forward Bill Wyker. ‘‘To play on a team with that much talent … to play in other cities and play in front of crowds is a big thrill.”

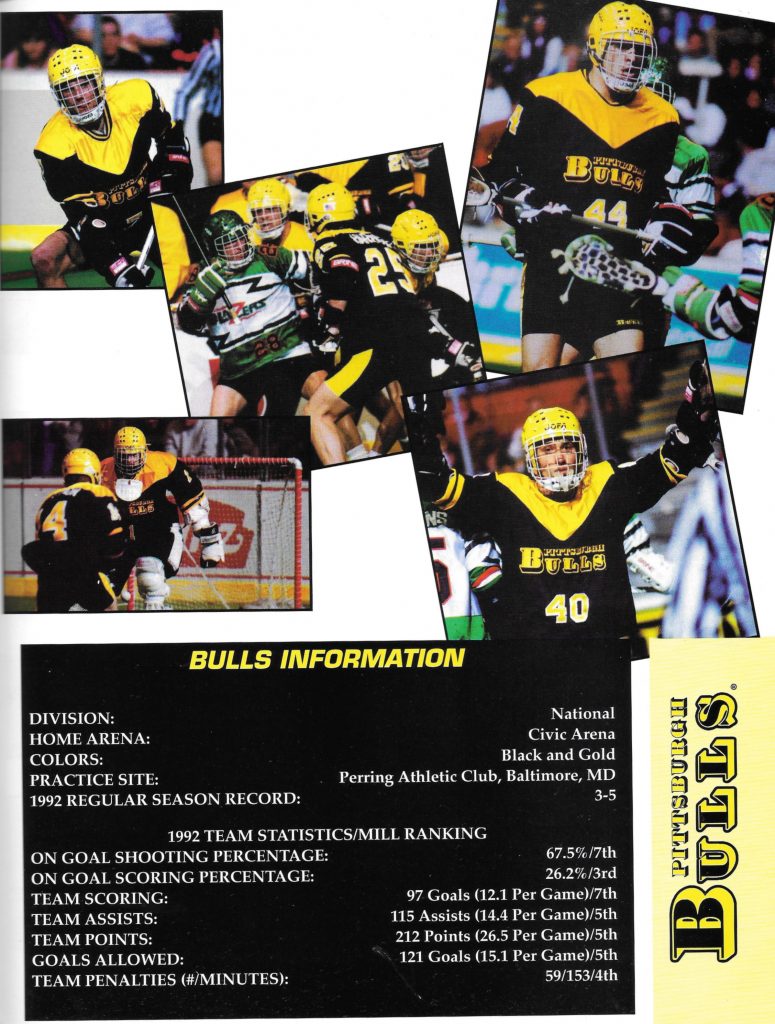

The Bulls, now 2-3, play at the Civic Arena. This season, their second, they have averaged more than 8,600 fans for the first three home games. The indoor game (also called box lacrosse) is an adaptation of field lacrosse, which is played in an area slightly larger than a football field. Because the indoor game is played in the more compact dimensions of a hockey rink, it is faster- paced, more intense and more physical than the outdoor version.

‘‘I like the fast pace… the up and down action all the time,” said Bulls forward Tim Conway. “It’s a physical game, too, which I enjoy.”

Every week Conway proves just how much he enjoys the game. He works as an assistant lacrosse coach at Pennsylvania State University and lives in State College. Each Thursday he makes a 2 6-hour drives to Baltimore, where the team practices. When he gets home at 2 a.m., he’s not ready for bed.

“I’m so wound up from practice I’m not tired,” he said. “I usually stay up for half an hour after I get home.’’

The Bulls are not to be confused with casual lacrosse players. Several college All-Americans play for the Bulls, and defensive standout Dave Pietramala, a Johns Hopkins graduate, was named MVP of the 1990 World Games, an international lacrosse competition held every four years.

“Some of the players in the league were just steps away from professional baseball or football,” Marino said. Speaking of pro baseball, Marino’s sidearm shot has been clocked at 102 mph, speedier than Nolan Ryan’s fastball or Paul Coffey’s best slapshot. And Marino’s shot is not the fastest on the team.

The Bulls come in sizes as large as 6-foot-4 and 210 pounds and have undeniable athletic abilities, starting with stick-handling skills comparable to those of hockey players. Working the stick with both the right and left hands is a must, and behind-the- back passes — and even shots — are not uncommon.

Indoor lacrosse, popular on the amateur level in Canada, is believed to have sharpened the skills of future National Hockey League players, including Wayne Gretzky.

In lacrosse, “How individual you are is related to how good you are with the stick,” Gold said. “I played baseball, football, track, soccer and basketball on organized teams in all those sports. Lacrosse is a sport that challenged me in every aspect: physically, mentally and emotionally.”

So what do the players think of indoor lacrosse’s reputation, in some quarters, as a circus of hard-hitters with a sideshow of violence-loving fans?

“I’m offended by that,” said Pietramala. “I know how hard we’re working for so little money to spread the popularity of the sport. When you criticize the game and say it’s not a pro sport, I think that’s wrong.”

“When the league first started, they were advertising it as violent,” said Wyker, a veteran of all five MILL seasons. “There was more violence in the first year, especially. Each year they’ve toned down the violence.”

The play is physical, but fights are less common than in the NHL. Like other athletes, the lacrosse players make a distinction between a hard hit and a cheap shot. Gold acknowledges, however, “There is an element in the league of goon-style players.”