by Steve Holroyd (laxmavn@aol.com)

Even though the 1930s found the United States in the midst of the Great Depression, the worst economic crisis it has ever faced, enterprising individuals insisted on starting up professional leagues in a number of sports.

Why? Perhaps it was to discover the “next big thing”—major league baseball had done well, but it was an exclusive club, not accepting any new members. And, as the folks behind the Federal League found out, challenging the baseball status quo was an exercise in futility. As a result, plundering other sports was the only viable option.

Even though the highly successful original American Soccer League had collapsed directly as the result of the Depression, a second version with the same name started up in 1933; although this league survived until 1983, it was barely professional for most of its history and, in any event, was far from a success.

As soccer was not the most “American” of games even then, others turned to profit from team sports that were already very popular in college. Although the National Football League started in 1920, it, too, was a largely chaotic, semiprofessional league for its first decade, as gridiron fans were slow to embrace professionalism in what was considered a “pure” sport in college. The signing of Red Grange in 1925 by the Chicago Bears finally gave the league some legitimacy, and by the 1930s it had finally abandoned its Midwestern roots, as teams from Decatur, Portsmouth and Canton were replaced with major cities like New York, Philadelphia, and Detroit (in fact, Green Bay is the only remaining vestige of those early cities). Pro football would be here to stay, even if it did not become the de facto national pastime it is today until about 1960.

As the other major college team sport of the era was basketball, a number of pro basketball leagues rolled out in the 1930s, as well. The first attempt was in 1925, with the original American Basketball League, but it collapsed in 1931. It returned in 1933, however, but never rose above minor league status even as it survived until 1955. In the interim, the National Basketball League formed in 1937, and merged with the Basketball Association of America (which formed in 1946) to create the National Basketball Association in 1949. However, even the NBA did not hit its stride as a stable, profitable league until the 1980s, with the arrival of Larry Bird, Magic Johnson, and Michael Jordan.

Lacrosse was not left out of the rush. While field lacrosse had been around for decades, there was little thought to professionalizing the ancient Native American game—presumably because no one wanted to compete against baseball. However, the indoor game of box lacrosse was invented in 1931—and, apparently, for the sole purpose of having a new professional sport to market. No sooner had the new sport been minted than the International Lacrosse League had formed in Canada, only to fizzle out after a season and a half.

This failure did not deter American sportsmen, however. In 1932, the American Box Lacrosse League was formed; played outside in boxes erected in baseball stadiums during the late spring, the league collapsed in about a month. In 1939, the west coast got into the act with the Pacific Coast Lacrosse Association. This time the sport was played indoors, and in the winter; it, too, collapsed within a month.

In between these two leagues was a third attempt. Given the fact that the other leagues covered the east and west coasts, respectively, it is only fitting that this circuit was set primarily in what was then considered the Midwest.

In late 1933, the North American Professional Lacrosse Association was formed. The backers of the league had seen box lacrosse’s indoor debut at Madison Square Garden in New York in May 1932 and loved what they had seen. While they also had the chance to watch the ABLL collapse, they decided that the failure of that league had nothing to do with the sport, but with the decision to hold the season outside, in the summer. “Box lacrosse is the sport of the future,” one can easily see them thinking, “and we’re the ones who can market it correctly.”

In what would be a common theme in pro boxla history, the primary movers behind the league were people looking for extra dates for their hockey arenas. The original movers and shakers behind the league were from St. Louis, and the original franchises were reported to be in Chicago, Milwaukee, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Buffalo, Toronto, Pittsburgh, Detroit and Rochester. All of the teams had “leased the biggest and best halls in these cities in order to have plenty of space for the indoor game, as well as to handle large crowds.”[1] The season was scheduled to begin on November 15 and run until April 1.

Looking long term, the new league molded itself on major league baseball in the sense that the “North American Professional Lacrosse Association” was the umbrella organization for two other “leagues” (in reality, divisions): the National Lacrosse League and the American Lacrosse League. The inaugural season would find three teams in each division, but initial interest was such that a third league—the International Lacrosse League—was slated to begin play in 1934-34.

Unfortunately, all of these names led to rampant confusion in the press, who would refer to the league by each of those names, or combination thereof (“American & International Lacrosse League”). This confusion was foreshadowing for how the league would soon operate.[2]

Games would be one hour long. In the event of a tie at the end of regulation, teams would play two ten minute “sudden death” periods; if the game was still tied after the conclusion of those overtime periods, the game would be declared “no contest.” Teams would receive two points per win in the standings.[3]

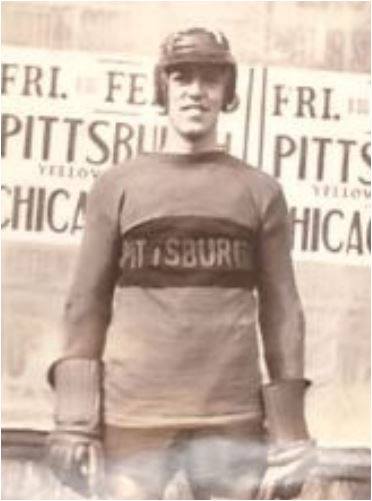

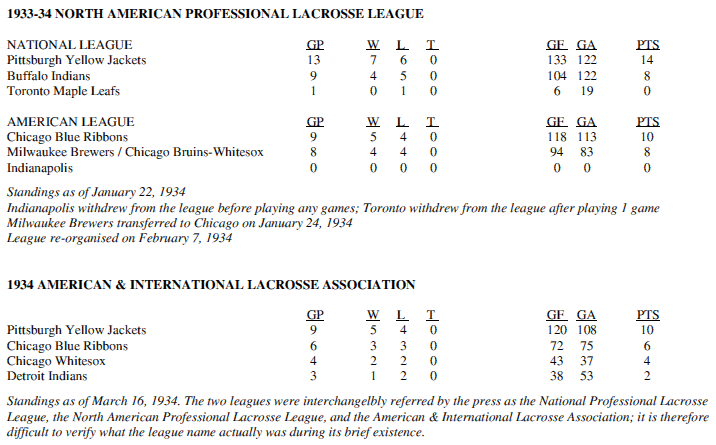

Notwithstanding earlier reports, the league did not start until mid-December, and with only six teams: in the National League were the Pittsburgh Yellow Jackets, Buffalo Indians, and Toronto Maple Leafs, while the American League consisted of the Chicago Blue Ribbons, Milwaukee Brewers, and Indianapolis.

Pittsburgh was a relative late-comer to the circuit, but made up for lost time by simply importing another team to represent the city: the Montreal Canadiens box lacrosse team, described in local papers as “world champions” by virtue of their having won the 1931 International League.

With its first few weeks, however, the league was down to four teams: Toronto bailed after one game, and Indianapolis not only folded before playing a match, but apparently never even got around to getting a nickname. Now just the “National League,” the circuit soldiered on.

The four remaining teams were highly competitive, at least. Given their pedigree, it was no surprise that Pittsburgh would rise as the best team, featuring the likes of Al McLean, Norm Langevin, and Leo Boulaine. Steel City natives appreciated the effort, as the Yellow Jackets were by far the most supported team in the league. Indeed, Pittsburgh games were regularly broadcast on the radio.

The other three teams were also competitive. The Buffalo Indians had players who were listed as “Silver Heels,” “Chief Tecumseh,” and “Little Elk”—in some cases authentic tribal names, but many mere nicknames adopted for publicity purposes—but who were actually players who had starred on the Atlantic City Americans team that toured the United States and Canada successfully in 1932, and included familiar faces like goalie Judy “Punch” Garlow and Harry Smith.

Chicago Blue Ribbons were owned by the irrepressible sports promoter Mike “Mique” Malloy, and played out of the Arcadia Gardens, located on 4444 Broadway Street in the Windy City. Featuring for the side was former Penn State football and lacrosse star, Bill House, along with Leonard “Fat” Plummer, Toots White, Piper Bain, and goaltender Bill McArthur. Former Chicago Black Hawk Corbett Denneny was tabbed to coach the side.

A promoter by trade, Malloy worked hard to generate excitement for lacrosse, offering:

“Why, this game has all the thrills of the rest of the sports put together. You’ve got to be able to take plenty of abuse, and they don’t have any padding on those lacrosse sticks. and one of the first things I’m going to try to find out is how far those fellows run during the course of a game. Why, I bet their mileage, straightened out, would carry from here to there.”[4]

Notwithstanding such efforts, other than in Pittsburgh, crowds were hard to come by. By late January, the Milwaukee franchise relocated to the south side of Chicago, giving the Windy City two teams. The second Chicago team was also operated by Malloy, who promised to fill the side with players from Baltimore, the “lacrossest city in America.”[5] In the end, he stuck with Milwaukee holdovers goaltender Tillie Stokes, forward Chuck Davidson, and player-coach Kelly DeGray. Known alternatively as the “Bruins” or “Sox,” this side would give Pittsburgh the strongest opposition in the league, playing out of Dexter Park Pavilion. Michael Agazin assumed control of the Blue Ribbons.

With the transfer of Milwaukee to Chicago, and the Buffalo team dying from lack of fan support, the league abruptly declared that the season to date would be a “first half,” and that a second half—with Detroit replacing Buffalo, would begin on February 16. Pittsburgh, as winners of the first half, would face the second half winner in a championship, if necessary. Confusingly, the “second half” league was often referred to as the “American & International Lacrosse League,” giving the impression of a new league.

The utter chaos was best described by an anonymous scribe in Chicago:

The la crosse [sic] situation in Chicago is as clear as a glass of river water…[T]he Milwaukee team now plays for Chicago, but…the former Chicago team is going to play for Chicago, too. Milwaukee is still in the league, but does not have a team. Detroit is going to place a team in the league, but it hasn’t hired any players. Last night the Chicago [Bruins] players wore Milwaukee uniforms.[6]

The three holdovers continued right along. However, Detroit had difficulty starting its schedule, as U.S. Customs would not let the natives who made up the Buffalo team (and were from Canada) cross the border until certain issues were resolved.[7] In the end, Detroit formed a team from scratch, and proved to be respectable—even defeating Pittsburgh. However, “crowds” of 200 for games in the Motor City did not bode well.

(Rare video footage of the Pittsburgh and Detroit teams practicing can be viewed here)

After a month, the second half ended, with Pittsburgh again at the top of the standings, followed by the Chicago Sox.

While there was no formal announcement that the league was folding, its death knell was effectively rung on March 15, when the Motor Street Arena announced it was evicting “minor” sports like box lacrosse and boxing by April 1 so it could free up dates and seek “major” touring events like the circus. With the league’s most successful team without a home, there was little incentive to reorganize for the following season.

Although there

would be a third attempt at pro boxla five years later, by the end of the

decade there would be three professional leagues that had come and gone within

the space of a few months. It would be

almost thirty years until there would be another attempt.

[1] “Indoor Loop of Pro Stick Teams Makes Debut This Winter,” Baltimore Evening Sun, October 13, 1933

[2] Id.

[3] “Form National La Crosse Loops,” Bristol (PA) Daily Courier, December 30, 1933

[4] “Malloy Tells Of Thrills In Lacrosse Game,” Chicago Tribune, January 26, 1934

[5] Dwyer, Patrick, “Blue Ribbon Lacrosse Team Wins, 14-4,” Chicago Tribune, January 6, 1935

[6] “New Chicago Lacrosse Team Wins, 11 to 7,” Chicago Tribune, January 29, 1934

[7] “Lacrosse Game Off; Immigration Trouble,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 21, 1934