by BILL GLAUBER – BALTIMORE SUN – March 3, 1991

Pre-game at the Baltimore Arena:

In a filthy locker room that smells like week-old cheddar cheese and looks like a rest stop from hell, 18 players sit listening to a school administrator-turned-coach.

Some of the players wrap tape around the handles of their lacrosse sticks. Others stare at the blackened carpet, which once upon a time might have been blue.

The coach, John Stewart, is writing numbers on a chalkboard. Once, he led Loyola High School to two Maryland Scholastic Association lacrosse titles. Now, he is struggling to decipher another game. With the patience that comes from being an assistant headmaster at Loyola, Stewart details the last 2 1/2 seasons of the Baltimore Thunder, a team on a .500 treadmill.

“I said at the beginning of the season that we wouldn’t be mediocre,” Stewart shouts. “That record right there is mediocre. Tonight, we’re asking for the ultimate sacrifice.”

The team gathers for a prayer. Stewart and his assistant coach, Paul Hoffman, then leave the locker room, and the players stand in a circle, chanting, cursing, clapping their hands, smacking their helmets.

This continues for two minutes.

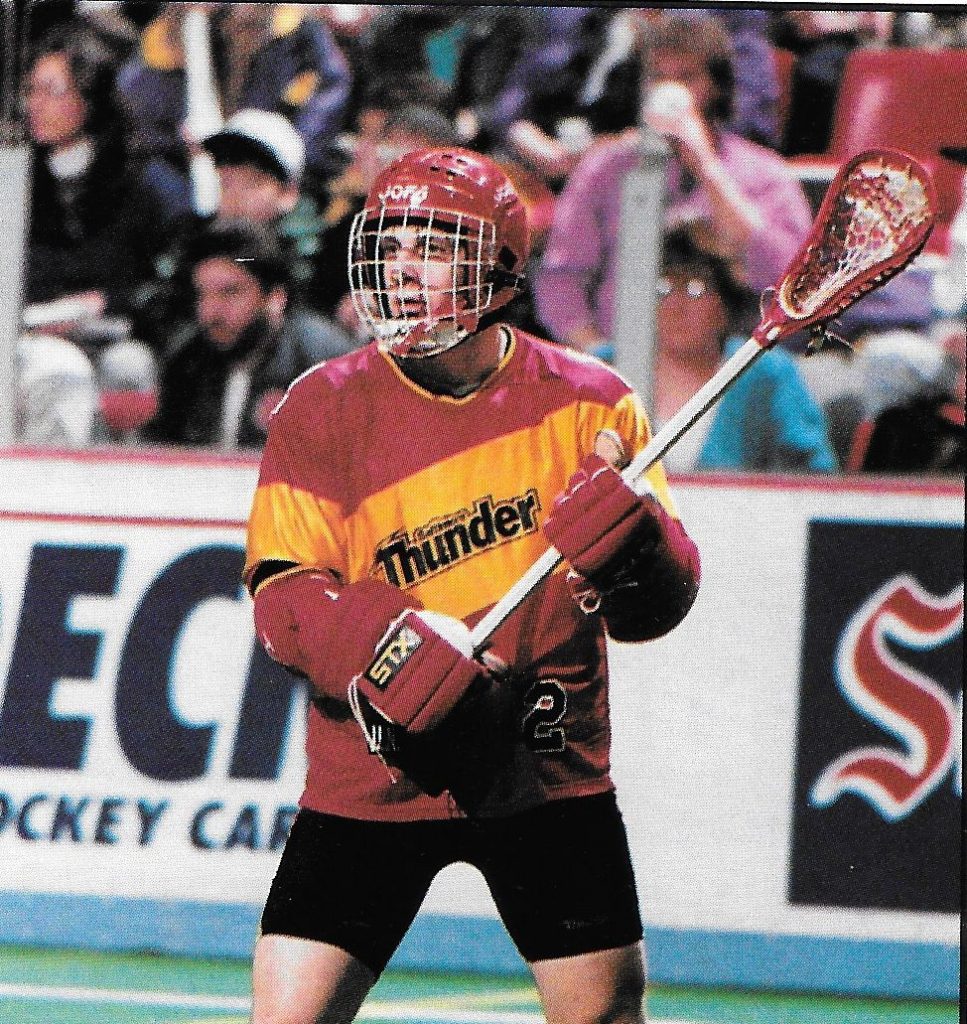

A harried attendant bangs on the metal door, shoves it open and yells, “You’re on. You’re on.” The players sprint through a hallway, down six steps and into the darkened arena. Music is playing. Names are blaring over a loudspeaker. The 8,109 fans shriek. In the midst of the noise, a 23-year-old rookie named Brian Kroneberger, who graduated from Calvert Hall and Loyola College and who works as a salesman, screams: “It’s the Dome. It’s the Thunder Dome. It’s our Thunder Dome.”

Welcome to the Major Indoor Lacrosse League.

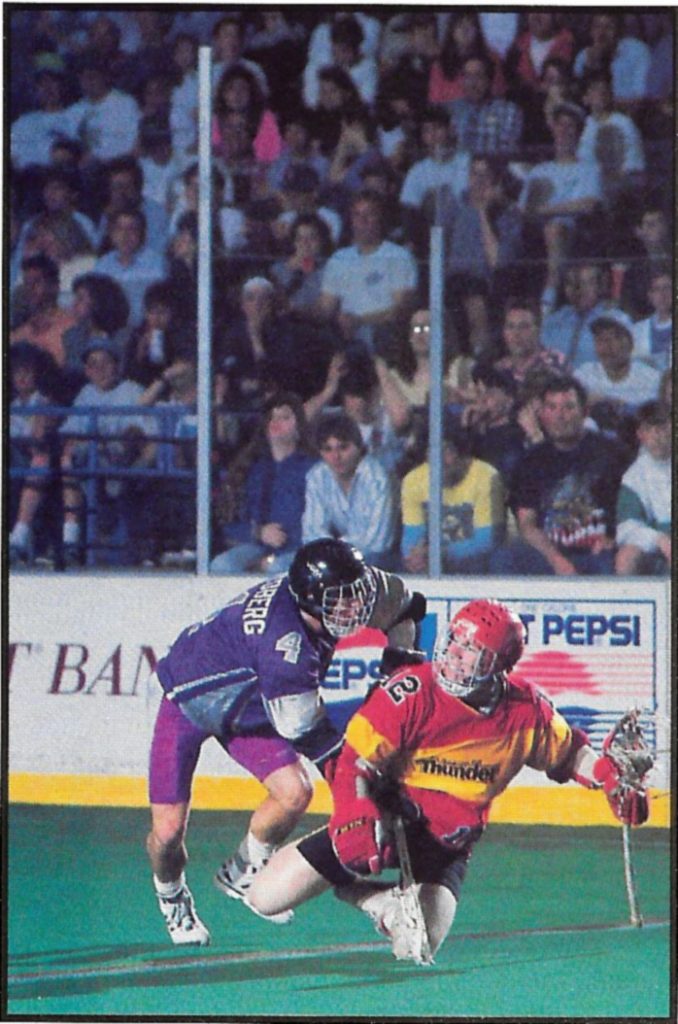

By day, they are teachers and insurance agents, stockbrokers and marketers, yuppies with car payments to meet, apartments to furnish, school loans to pay off. But on 10 weekends a year, they put on their helmets, lace up their shoes, squeeze into skin-tight Lycra shorts, pull over garish jerseys and emerge as professional players in a 5-year-old league.

The pay is awful, and the play is punishing. Broken noses, twisted ankles, pulled muscles and scraped knees are routine injuries. The rewards are few — friendship, eight complimentary tickets a game, 60 minutes in the limelight.

“Sometimes, I don’t even know why I do this,” said John Nostrant, who works days as a fifth-grade teacher at the St. Alban’s School in Washington. “It must be for the love of the game.”

The view from the bench: Baltimore vs. New York, Feb. 9, 1991. Second quarter. Tim Welsh bounces in a goal to give the Thunder a 7-5 lead. The crowd erupts. Tim and his brother Pat exchange high fives at midfield. Then, Tim performs his “Churn the Butter” dance. He grinds his hips like a stripper, jumps on the boards, grabs the Plexiglas with his left hand and raises his stick with his right hand.

Tim Welsh is 26 years old. He is a land developer.

Purists will tell you that this is not lacrosse. There are no grass fields, no definable positions, no long sticks, not even any golden retrievers to come stumbling out of the stands to interrupt play.

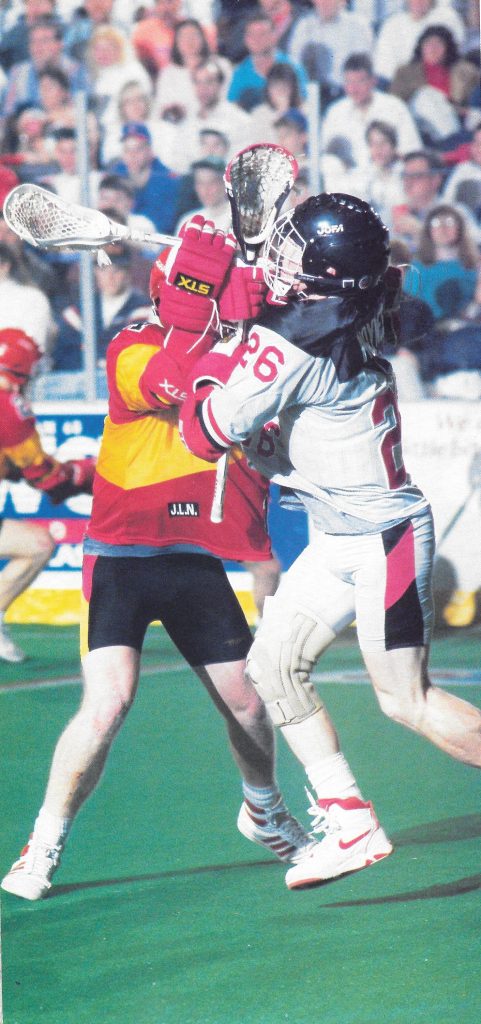

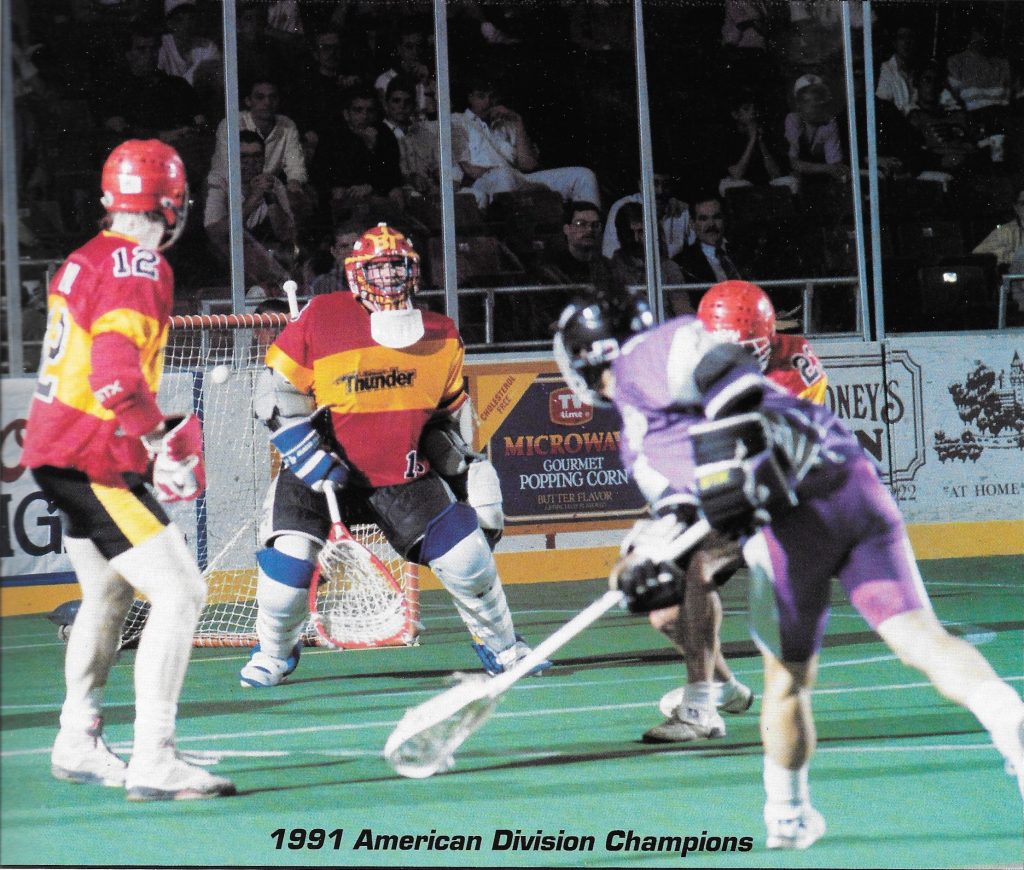

This is a mongrel game, one part hockey and one part lacrosse. Teams use five field players and one heavily padded goaltender who looks like a 300-pound Pillsbury Dough Boy and guards a 4 1/2-foot-by-4-foot cage. The field is the size of a hockey rink, with carpet substituting for ice, complete with dasher boards and Plexiglas. Games are divided into four, 15-minute quarters. Cross-checking is legal. Fighting isn’t. For some reason, there is a 40-second shot clock, but almost no one pays any attention to the time. Everyone is too busy shooting, running or body checking. Thirty-goal games are standard.

One more statistic: Two guys own the entire league.

Chris Fritz and Russ Kline, sports marketers based in Kansas City, Mo., run the operation. Back in the mid-1980s, they were looking to create the sport for the next century. They were about to plunk down their cash on some weirdo version of “Rollerball” — roller derby meets football — when someone suggested they go to Canada to watch a box lacrosse game. Entranced by the product, they decided to set up an indoor league in the United States, even though a previous indoor lacrosse league failed.

“We studied every league, and the one tying thread of failure was the inability to get owners you could tie together as a group,” Kline said. “We decided to own the league and the teams. We didn’t care who won. We won either way. Because we were able to control the salaries and get cooperation of the buildings, we had a chance to succeed.”

They set up shop in 1987 in four cities — Philadelphia, New York, Baltimore and Washington — and called their business the Eagle Box Lacrosse League. Because Fritz and Klein were the only two people who knew what EBLL stood for, they changed the league’s name before the second season, settling on the Major Indoor Lacrosse League.

There are six teams this season. The Detroit Turbos, Pittsburgh Bulls and New England Blazers comprise the National Division. The Baltimore Thunder, New York Saints and Philadelphia Wings make up the American Division. Teams play 10-game schedules, and, yes, there will be a playoff to determine a “world champion.”

The MILL splits its take with the arenas, keeping 60 percent of the gate after taxes. In Philadelphia, 16,000 fans routinely attend games at the Spectrum. Even league officials are happily baffled by high attendance there.

Players are on a pay scale. Rookies receive $125, and second-year players earn $150. From there, the scale rises by $50 for each year of service, up to $300 for fifth-year players.

Total player payroll: $200,000.

“We’re not asking people to quit their jobs, give up their careers and support their families,” Klein said. “We want to work around their career development. Without them, we wouldn’t have a league.”

The view from the bench: Third quarter. Vince Angotti of the Thunder and Tommy Towers of New York turn a scramble for a loose ball into a wrestling match. When Angotti’s helmet comes off, Towers takes the opportunity to rub the player’s nose into the carpet. Baltimore’s Todd Canby, a UMBC graduate who has invited to the game some of his clients from his sales rep job, jumps on the pile and is ejected.

Moments later, Angotti and Towers are sitting across from one another in the penalty box. They’re smiling.

“I went to Cornell, and he went to Brown,” Angotti would say later while looking down at his two scraped knees and rubbing his scraped nose. “We’ve known each other for years. Imagine, two Ivy League guys going at it. You know, my mother always said she didn’t like this game because it promotes violence.”

The game brings them back. They graduate from college, move into jobs and discover that they’re too young too give up sports. Playing indoors is a chance to prolong youth, to hold on to the joy of performing in front of fans, to feel the thrill that comes with each victory.

They would do this for free.

Why? It’s a ridiculous question.

“You feel like a star at the end of the game when all the little kids come up to you asking for your autograph,” Tim Welsh said. “That’s nice. You actually feel like a pro athlete, even though it’s more like a hobby.”

Or a release.

Jim Huelskamp, five-year veteran, lost his job when a round of layoffs was announced at USF&G; in January. He takes his frustrations out on the field. Bashing foes. Running free. Answering to no one, except his teammates and the referees.

“You look forward to the weekends,” he said.

Steve Beardmore, who tore his anterior cruciate ligament in his right knee in a water-skiing accident seven years ago, said he plays “because I didn’t get a chance to have a taste of the game in college.”

Even those who played four years in college want more. Rick Sowell, the assistant lacrosse coach at Georgetown University, broke a bone in his back after absorbing a hard check in a game last season. He is 27 years old, one of the oldest players in the league, and he refuses to quit.

“I laugh when people say I’m a pro athlete,” Sowell said. “I take it for what it’s worth. Great competition. Tough play. Good friends.”

This season, John Nostrant is playing for fun and for therapy. His father John Sr., died of cancer last fall. Father and son often argued about the game. Introspective and gentlemanly off the field, John Nostrant is a rambunctious player who drives opponents to fury.

“My dad said to me that I play out of character,” Nostrant said. “I said, ‘Dad, you have to play out of character for two hours.’ I don’t care if anyone likes me. They could take my head off. I’ll buy them a beer after the game. Everyone has a fear. You don’t want to blow a knee out. I mean, this isn’t your job.”

The constant refrain about life in the MILL is this: Don’t give up your day work. The pay barely covers transportation. One player who did leave his job to play is goalie Jeff Gombar, of Poor Moody, British Columbia, a town just outside Vancouver. After spending four years at Whittier College and working for a year as a sales representative, Gombar decided to give the indoor game a try. He wrote the Thunder asking for a tryout, purchased a round-trip air ticket and arrived in Baltimore in October lugging 60 pounds of goalie equipment.

“I’m living out a goal of mine,” Gombar said. “I wanted to play big-time lacrosse.”

One month ago, Gombar took a shot in the face that broke his nose in 11 places. He missed only one practice.

“Hey, we’re not making $1 million a year,” Gombar said. “But we’re pros. Most of us are used to playing in front of only a couple of hundred people. Do you know what kind of rush it is to play in front of 8,000, 10,000?”

The view from the bench: Fourth quarter. Organized disorganization. Water bottles and stick handles are strewn on the floor. Players are standing. Shifts grow shorter. The three lines — nicknamed Moe, Larry and Curley — work beautifully. The clock is ticking toward zero.

Gombar is stretching his legs, trying to get rid of leg cramps. He played splendidly in goal for three quarters, but fatigue finally forces him out of the game with the Thunder clinging to a two-goal lead. Gombar is screaming at his teammates to protect his replacement, Tom Manos, a former three-year starter at Towson State. Stewart is screaming at his players to freeze the ball. The crowd is cheering as Manos dips low to stop a flurry of shots. New York scores a goal at the buzzer, and the crowd is silenced. Players mill around the field waiting for directions from the officials. But Manos is hopping joyfully from his cage, shouting: “Big deal. Big deal. We win.”

Final score: Baltimore 15, New York 14.

Post-game at the Baltimore Arena.

The players gorge on hot dogs, sodas and cookies. They shower and dress quickly, trying to race out of the locker room to a post-game party.

Darrell Russell, a Baltimore County District Court judge who moonlights as the team’s general manager, distributes the paychecks and picks up the uniforms. Stewart, drained from nearly 2 1/2 hours of tension and yelling, sits in a corner, sips a soda and says, “They earned their money.”