by Steve Holroyd (laxmavn@aol.com)

In between 1968-72, three separate attempts at professional lacrosse had been attempted; each were “one-and-done” after a single season.

Nevertheless, the Sports Boom of the 1970s was such that would-be moguls were inclined to think that they could build a better mousetrap, and succeed where their predecessors failed. One such dreamer was Daniel Snyder, head of Maryland-based Main Event Sports.

Snyder, a former All-America lacrosse player who was also co-captain at the University of Maryland, had gone on to graduate from University of Baltimore Law School.[1] But he had little interest in practicing law. Instead, he was drawn to sports promotion.

Earlier in 1973, he defied the odds and successfully staged high school basketball at a major level in Baltimore, drawing 8,500 fans to the Civic Center to watch a clash between two undefeated teams. This success no doubt whetted his appetite for more: a professional league in the sport he loved.

Rumblings

In April 1973, Snyder, along with former United States Club Lacrosse Association president Matt Swerdloff, was actively trying to establish a professional lacrosse league. This time, however, the focus would not be on the indoor game, but field lacrosse. Current USCLA president Joe Harlan encouraged the move.

Not surprisingly, there was a fair amount of skepticism among the men who were stewards of college lacrosse. For instance, Towson State coach Carl Runk offered, “To me, pro lacrosse is a dream at least for the present. I can’t see it happening for at least another 10-15 years.” “When we can sit back and see 20,000 at Navy-Marine Corps Stadium, 11,000 at [Johns] Hopkins and 15,000 somewhere else in the area over the weekend, that’s when you can start talking about pro lacrosse,” added Navy coach Dick Szlasa. “The people in lacrosse are stone optimists,” scoffed Runk.[2]

Unable to break the college stranglehold on the game, a pro field lacrosse league was a non-starter. But Snyder was not going to give up so easily.

A Summer Series

In June 1973, Snyder—along with co-promoter Larry Levitt—announced a summer box lacrosse series featuring a team of U.S. field collegiate and club stars facing teams from Canada.

Why box lacrosse, after previously making noise about a pro field league? Snyder pointed to a recent survey. “There are several reasons why box lacrosse was a more marketable product [than field lacrosse],” he said, and cited several factors:

1. it offers more fan appeal on a national basis;

2. there are already semi-professional teams in Canada;

3. many big city arenas are looking for tenants after ice hockey season;

4. playing indoors provided security against inclement weather;

5. advantageous for television coverage

Noting that crowds from 3,000 to 8,000 regularly attended box lacrosse matches in Canada between May and September, Snyder was hopeful similar interest could be generated in the eastern United States to start a professional league in 1974. Snyder claimed that Toronto, Syracuse, New York, Chicago, Detroit, and Minnesota had already expressed interest in such a league.[3]

The series would find the U.S. Select Team going to Brantford to play the 1971 Mann Cup champion Brantford Warriors on July 29, with a second game against the Warriors to be staged in Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens on July 31. The two teams would then meet a third time, on August 14, at Baltimore’s Civic Center.

As fate would have it, Brantford was helmed by a man well-acquainted with professional lacrosse. Morley Kells was a key driver behind the National Lacrosse Association of 1968, and his Warriors were the champions of the latest stab at pro boxla, the National Lacrosse League of 1972. Kells attended a meeting with Snyder in Washington, D.C. on July 7, along with 20 other groups said to be interested in pro box lacrosse. “I agreed to be part of the exploration,” said Kells, who also claimed to own the right to pro lacrosse in Toronto. “But I’ll be very blunt with them.” Kells also indicated he was attending as part of a “fact finding” mission, not only on his own behalf, but on behalf of Detroit Red Wings owner Bruce Norris (who owned the NLA’s Detroit Olympics) and Buffalo Sabres owner Seymour Knox.

For his part, Snyder was sure any league could avoid the problems of the NLA. “In 1968 it just wasn’t the right type of promotion,” said Snyder, who primary aim was to convert field lacrosse players to the indoor game. “We’ll have to build heroes and villains…we’re looking for people interested in promotion, very solid groups.”[4]

Team America

While all this was going on, the United States “All-Star” lacrosse team began to prepare in earnest. Coach Buddy Beardmore and assistant Jim Dietz invited 28 trialists to the Bowie Ice Rink, from which a squad of 18 would be selected.

Beardmore was coach at the University of Maryland, and had just led his squad to the 1974 NCAA championship. Not surprisingly, the squad he ultimately selected was pretty heavy on Terps. Half the squad came from Maryland, including Frank Urso, Doug Schreiber (father of “Captain America” Tom Schreiber), and Bill O’Donnell. Rounding out the squad two players from Johns Hopkins; two from Mount Washington, and one each from Virginia, Washington College, Carling, Maryland LC, and Cornell. Cornell’s representative, incidentally, was Bruce Arena.

It should be recalled that box lacrosse was virtually non-existent in the United States, outside of cities along the Canadian border like Buffalo and Rochester. For most of the American players—and for its coach—boxla would be a brand new experience.

The series

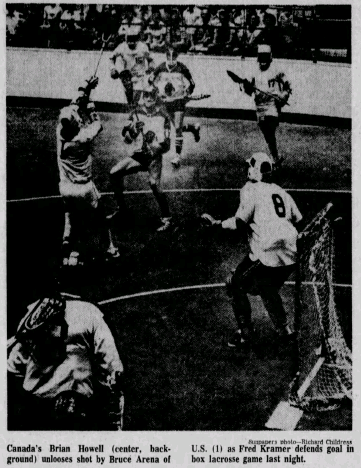

On July 29, the U.S. team trudged up to Brantford to face one of the best teams Canada had to offer. Not surprisingly, given the vast difference in experience, the Warriors toyed with the U.S. team en route to a 26-11 pasting.

The second game—originally set for the held in Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens—was instead moved to Syracuse. In addition, the opponent was changed—instead of facing Brantford, the U.S. faced the local Syracuse Warriors, a team made up of players from the Onondaga tribe of the Iroquois nations.

To their credit, the Americans quickly adjusted to the differences in the box game, and put together a much better showing in a 27-21 loss.

But an adjustment it was. For his part, Beardmore was close to a state of shock.

“I can’t believe what I saw up there,” said the former Maryland All-America midfielder. “I wish we had these two games on film so the people back home would know what we were talking about when we try to describe box lacrosse to them…You use a round ball and a stick, that’s the only similarity [to field lacrosse.] This box lacrosse is vicious. It’s ten times rougher than our field game, and our game [against Syracuse] was rougher than any hockey game I’ve ever seen…You don’t even have to be near the ball for somebody to come along and knock you on your tail. We had the feeling we were getting cheap shots all night, but we weren’t. That’s just the way you play this game. It’s all legal.”[5]

The physicality of the indoor game was not the only thing to which American field players needed to adjust. “The biggest adjustment is for the goalies,” Beardmore continued. “The goal is only 4 feet by 4 feet, instead of the six by six we use in field lacrosse. Syracuse had a good goalie who was 5-8 and weighed 260 pounds. He practically filled up the whole goal, but in this game they shoot from right in close.”[6]

“We had all these plays set up but they were worthless because of all the cross-checking in the game. A check to the ribs or onto the boards ended our plays quickly.”[7]

For Snyder and Levitt, though, the results in Canada were not important. Rather, their eyes would be on whether the game would prove popular at home.

American games

On August 14, Kells’ Brantford Warriors trekked to the Civic Center in Baltimore, and delivered a 29-11 whipping on the U.S. All-Stars. Paul Suggate—a name that would one year later become well-known to Maryland lacrosse fans—scored 5 goals and 6 assists on the evening. John Kaestner managed a hat trick for the home side. The Canadians were so dominant that they twice scored shorthanded goals with two men in the penalty box.

Getting crushed three games in a row was tough for the Americans to take. “Frankly, after being psyched for the first two games, there were a lot of fellows who couldn’t get up for tonight’s game,” said Kaestner. “It’s been a long summer. Most of us want to go to the beach and relax.”[8]

Not every American was deterred, however. Although Frank Wittelsberger said “I’ve had enough of box lacrosse for the present,” the Johns Hopkins alum quickly added that he would play if the rumored professional box lacrosse league came to light.[9]

The result was expected. The crowd, however, was a pleasant surprise: 5,140 fans came to watch the exhibition. Despite predictions of a crowd of less than a thousand, 4,044 paid to see the game, and everyone in attendance was said to have been impressed by what was an exciting, spectator-pleasing game.

Emboldened by the crowd, Snyder began to push the idea of a professional league. Claiming to have “some big money men” in Detroit ready to purchase a franchise, Snyder offered that, if he could secure arenas in Baltimore, Buffalo, Syracuse, and New York, “we’re on our way.”[10]

Ever the optimist, Snyder distributed an 8-page prospectus to the media. One section, entitled “Example Of A Schedule For A Six-Team League,” envisioned Baltimore playing at Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) on May 31, 1974, with other teams in New York, Long Island, Syracuse, and Buffalo. “The biggest obstacle right now is the travel expense,” said Snyder. “That, and the schedule. If we get those things ironed out, we’ll have a league in operation by December.” Snyder also claimed there as interest from a cable TV company to broadcast games.[11]

Snyder was hopeful for an even bigger crowd for the second game on September 9, against the Syracuse Warriors. This was especially so because the Syracuse team had just been featured in that week’s Sports Illustrated in an article entitled “Murder Ball in a Box”—Snyder must have thought that the stars were in alignment for his pro lacrosse league.

His enthusiasm took a hit when only about 2,000 fans came to watch the U.S. All-Stars rip the visitors, 23-10. Alas, some of the glow comes off this result when it is revealed that the Onondaga did not bring a full squad to the game. Perhaps bored by the lack of competition in the first meeting, or at the request of Snyder himself, especially after reading Kaestner’s remarks about players growing weary of the series, the Warriors roster consisted primarily of Native American high school and college players.[12] Kaestner, Frank Urso, and Pat O’Meally each scored hat tricks for the Americans.

Aftermath

Chided by the fact that the crowd for the second match was less than half of the first, Snyder’s zeal for a professional boxla league seems to have disappeared overnight. Indeed, even though a pro box lacrosse league would arrive less than six months later, Snyder was not a part of it. Apparently, Morley Kells and the “proxies” he referenced during the July 7 meeting took good notes, as all of the individuals mentioned there would be a part of the National Lacrosse League. But not Snyder.

The Baltimore promoter regretted his decision, apparently. As a result, in September 1974, Snyder was linked with Sean Downey, Jr.—the man behind a planned World Baseball League and World Team Boxing—as the men behind the American Box Lacrosse League, a west coast rival to the NLL. A number of cities were mentioned for the league, including Minneapolis, Chicago, Houston, Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Diego, Denver, Phoenix, Winnipeg, and Edmonton. Talk had Vancouver industrialist Jim Pattison owning the British Columbia team, while Jack Kent Cooke and Peter Graham would own the San Diego team. “Most of the people involved in [the World Hockey Association] are also interested in gaining a lacrosse franchise,” said Dave Fishman, the National Director of the Canadian Lacrosse Association, who was approached to be ABLL Commissioner.[13]

“The ABLL isn’t about to get into a bidding war with the NLL for players,” said Fishman, even though it appeared the new league was rushing its announcement to keep some western-based NLL players from re-signing for the 1975 season. “But we’re confident of getting our share of top players from the east and west. Our minimum salary will be $6,500.”[14]

The ABLL was to be formally announced on October 22 at the O’Hara Inn in Chicago. The press conference was cancelled, however, and the idea of a western league died as quickly as it came. Apparently, Downey was too deeply involved in getting his World Team Boxing project off the ground to devote sufficient time to the ABLL.[15]

While Downey was

surely busy, the fact that there was another

rumored west coast rival may have scared the ABLL off. At the same time as the ABLL rumors, it was

reported that Al Salviano—well-known for his efforts at spreading the sport of

lacrosse throughout California—had registered the name “International Lacrosse

Association” in California, and was hoping to start the ILA with teams in

Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego.[16] Of course, this effort also did not get off

the ground.

[1] Confusingly, other reports say he was a merely mediocre Maryland-area player. In fact, there may be two prominent “Dan Snyders” in Baltimore during the era, both with lacrosse experience (and one of whom was the basis for a character in the film Diner). In any event, one thing is clear: the Dan Snyder here is not the current owner of the Washington NFL team.

[2] Ibach, Bob, “Lacrosse Pro League? Rumors Are Premature,” Baltimore Evening Sun, April 19, 1973

In fairness, Runk was pretty accurate in his prediction: it would not be until 15 years later that a pro field lacrosse league was attempted, the American Lacrosse League of 1988.

[3] Ibach, Bob, “Box Lacrosse On Display With Eye To Pro League,” Baltimore Evening Sun, June 27, 1973

[4] Feser, Dennis, “‘Pro lacrosse? Show me cash’ says Morley Kells,” Vancouver Sun, July 7, 1973

[5] Tanton, Bill, “Box Lacrosse Called Rougher Than Hockey,” Baltimore Evening Sun, August 2, 1973

[6] Id.

[7] Free, Bill, “Box lacrosse tougher than U.S. stars thought,” Baltimore Sun, August 10, 1973

[8] Ibach, Bob, “U.S. Lacrossers Put In A Box By Canadians,” Baltimore Evening Sun, August 15, 1973

[9] Id.

[10] Attner, Paul, “Promoter Finds Calling in Box Lacrosse,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 23, 1973

[11] Janofsky, Mike, “Snyder Is Intent On Selling Game,” Baltimore Evening Sun, September 6, 1973

[12] As reported by Alvin George in a comment on the RetroLax Lacrosse Facebook page, December 28, 2018. George was one of the Warrior players that day.

[13] Jukich, Roy, “West pro boxla in works?,” Vancouver Sun, September 24, 1974

[14] Id.

[15] Downey managed to get World Team Boxing off the ground; the league debuted on January 16, 1975, in Portland, Maine, with the Montreal 76ers defeating the Maine Nor’Easters, 13-4. The scoring: 3 points for a KO, 2 points for a decision, and 1 point each for a draw.

After initially announcing a goal of 50 teams in 48 cities, Downey eventually scaled down to an eight team league: Montreal, Maine, Boston Boxers, Providence (RI) Pistols, San Jose Prunes, Buffalo Rainbows, New York Pets, and—justifying the “world” theme—Virgin Island Caribs. (Minneapolis Belters and Trenton (NJ) Wolverines were around long enough to be named, but were dropped before the league’s January 1975 debut.)

Boxers earned a $100-per-week minimum. Teams had 10-man rosters; any boxer below “main event” level was eligible to be signed. Bouts would be 6 rounds, with six weight classes contested. The season would run from January to June. The league champion would be awarded the Muhammad Ali Cup; the Joe Walcott Trophy (named for the league’s commissioner) would go to the most gentlemanly boxer; and the Rocky Marciano Award would go to the league’s MVP. Ali himself was a proponent of the team boxing, as were many other legends of the sport.

The league folded right after its first match.

Notably, only 235 paid to attend the event. This inauspicious debut was not the reason for the league’s demise. Rather, it was the fact that, immediately after the match, the league suspended three teams owned by Boston lawyer Frank Opie (Maine, Providence, and Boston) for “conduct detrimental to boxing”—specifically, failure to pay league assessments and the $10,000 franchise fee, as well as a failure to pay the fighters. While some last-ditch efforts were made to keep the concept alive, those failed.

By the way, you may know Sean Downey better by the name he took in the 1980s as a talk show host: Morton Downey, Jr.

[16] Fedoruk, Ernie, “Lacrosse Blossoms,” Victoria Times Colonist, September 27, 1974