By Jay Searcy, INQUIRER STAFF WRITER

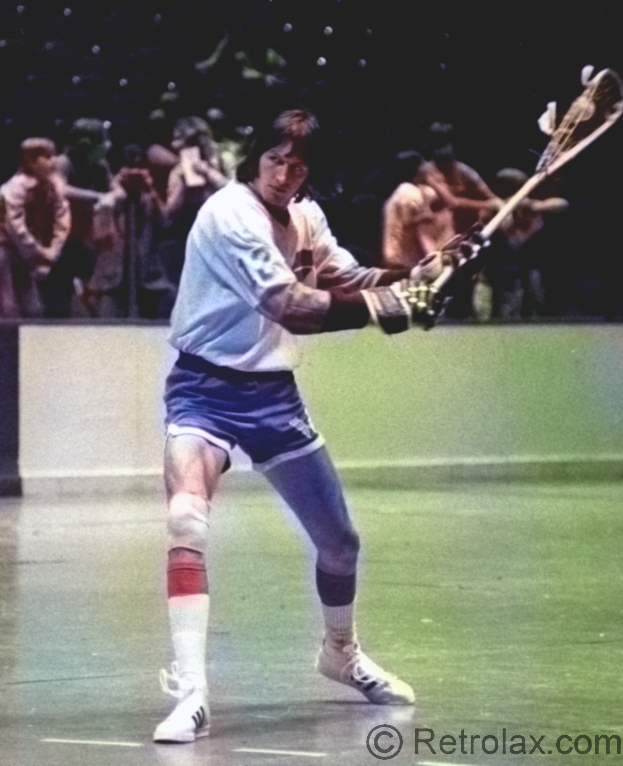

They will be playing Canada’s national game at the Spectrum tonight. You know, the game with the sticks and pads and gloves and helmets and goalies and body checks and penalty boxes and sneakers.

Sneakers?

Yeah, sneakers. You thought they used skates to play Canada’s national game, eh? You thought hockey was Canada’s national game?

It isn’t now and never has been. It’s lacrosse, the old Indian game that was played on the fields of Canada long before there were ice rinks.

True, lacrosse was overshadowed early this century by ice hockey, but as popular as hockey is now in Canada, Parliament has never bothered to change the books, so officially the national game is lacrosse and has been since 1867.

“Today,” said Dave Evans, coach of the Philadelphia Wings, “lacrosse in Canada is like soccer in the United States. Everybody grows up playing it, but nobody watches it.”

Well, almost nobody. They are expecting a near sellout crowd of more than 17,000 tonight when the 6-1 Wings of the Major Indoor Lacrosse League close out their regular season against the Pittsburgh Bulls. And a strange mix that crowd will be.

Because lacrosse is a rough-and-tumble sport, it attracts a blue-collar following. Because it is played mostly at private schools in the East and by Ivy Leaguers, it attracts the preppies. And because it is a relativly cheap night out – $12 to $17 a ticket – it attracts the young set.

The crowds at the Spectrum for three home games this season have averaged 16,358, and in six years, the Wings have had only one crowd under 10,000. All that with virtually no publicity.

There’s a Wings fan club with more than 700 members, and if Philadelphia and undefeated, top-seeded Buffalo make it to the playoff finals on April 3, about five busloads of fans will likely follow the Wings to Buffalo.

“The appeal,” said Evans, 43, a native of Vancouver, British Columbia, who has been the Wings coach for six of the seven MILL seasons, “is that it is nonstop action – no offsides to stop play, no icing. Virtually no fighting, because in field lacrosse fighting is taboo.”

But players break an armload of stick handles every game, flailing and whacking one another and whipping a hard rubber ball toward a net at blinding speeds. It’s like a pickup basketball game with sticks. If an opposing player is in your path, don’t go around him. Put a stick on him and shove him out of the way.

“Actually,” said Evans, “it’s not as bad as it looks. The heads of the sticks are plastic, and the handles are hollow aluminum, so you can’t really do a lot of damage. You chop a guy on the gloves or arms and the shock is absorbed mostly by the head of the stick. It may sting but . . . ” But not many broken arms?

“Right,” he said, “The arms, the back and kidneys are protected by pads. The worst injuries we have are rug burns. In six years we’ve never had a serious injury.”

The Wings have two attractions that other MILL teams don’t have – Paul and Gary Gait, 25-year-old identical twins from Victoria, British Columbia, who may be the best the game has ever seen. They were three-time all-Americans at Syracuse and led the Orangemen to three staight NCAA championships. They are to indoor lacrosse what Julius Erving was to basketball.

“They are probably the most skilled ever to play the game,” said Evans. ”A few others have done some of the things they’ve done, but they were probably 5-8, 160 pounds. No one with their skill and size has ever done what they do. They’re like two tight ends, 6-2, 215 pounds. They pass behind their backs, between their legs, reverse backhand. If they don’t go around you, they go over you.”

So the Gait twins are attracting large crowds and parlaying their skills into fortunes in pro lacrosse?

They wish. Actually, they get $200 a game, like every other third-year player in the league, superstars or not, and if they’re lucky in the playoffs, they may get another $400 in bonuses. Salaries are earned by seniority, no player makes more than $400 a game, and there are only eight regular season games a year. So no fortunes are being made in the MILL.

Evans, who makes $450 a game like all MILL coaches, actually loses money each season when he takes a two-month break from his job as greenskeeper at a private golf club in Vancouver.

But if you think players don’t make much in the MILL, consider what they do when the season is over.

“They play field lacrosse for nothing,” said Evans, “before crowds of maybe 50.”

(Philadelphia Inquirer, March 14, 1993)