by Steve Holroyd (laxmavn@aol.com)

Do enough sports history research, and you’ll learn that certain patterns get repeated over and over again.

For example: if I told you about a league where all the teams were owned by the same people, bringing a “new” sport to fans, you might think I was talking about the Eagle Pro Box Lacrosse League of 1987. If I added that the four teams—ostensibly from different cities—played all of their games at the same arena, you might instead think I was referencing the American Roller Derby League, where teams called “New York Demons” and “Chicago Pioneers” all played out of an arena in northern California.

However, the “single entity/single location” league concept first popped up fifty years earlier, when a group of Los Angeles promoters decided to form the third professional box lacrosse league in the United States: the Pacific Coast Lacrosse Association.

The brainchild of Los Angeles promoter Frank Sweeney, in late 1938 he announced plans for the creation of an indoor lacrosse league which would play games in the winter at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles. But why a box lacrosse league, given the rapid collapse of the American Pro Box Lacrosse League six years earlier and the similar failure of a Midwest league in 1934? For that matter, why California, which did not have a deep history with the game at that time?

It is tempting to think the promoters were looking to attract Canadians who had moved to the Golden State to support the sport…but, when it is recalled that the game of box lacrosse was only about seven years old at that point, it is not like there was yet enough “nostalgia” among that market to make such a venture viable.

A more likely reason was that Sweeney and his backers wanted to take advantage of the excitement generated by the Golden Gate International Exposition, which was going to take place starting in February 1939 over 288 days on Treasure Island, a new island in the middle of San Francisco Bay. Among the 300 sporting events to be held was box lacrosse, which had already acquired a reputation in the United States of being not only the “fastest game on two feet,” but also one of the most violent.[i]

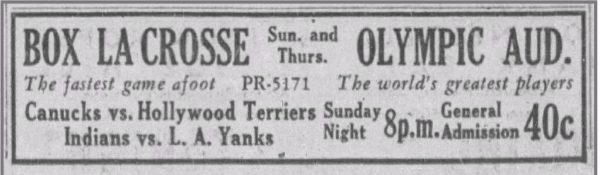

In any event, the PCLA was scheduled to begin play in January 1939, with teams playing twice a week—Thursdays and Sundays—and was slated to run for just over two months.

“California, here I come…”

To their credit, movers behind the new circuit made sure to acquire top talent to fill the rosters of the four teams, and enlisted the aid veteran British Columbia lacrosse referee Jimmy Gunn for that purpose. The Los Angeles Yankees, so named because the team was made up primarily of stickmen from the east coast, were coached by Cliff “Doughy” Spring, long-time star with the storied New Westminster (British Columbia) Salmonbellies, and included: Lou Robbins, an All-American from 1934-36 with Syracuse; Peter “The Great” Anthony, Bill Cook, and Beau Bradford.[ii] The Hollywood Terriers would be coached by Bill Curran, and made up primarily of players from the Orillia (Ontario) Terriers, three time box lacrosse “world champions”[iii]; the Canucks, who were actually the New Westminster Adanacs (“Canada,” spelled backwards), coached by Lloyd Steele, “one of the smartest men playing ‘the fastest game on foot,’” and featuring “Punk” Taylor, “the ‘Robert Taylor’ of lacrosse,” goalie Herb Delmonico, and 18-year old Garnie Carter[iv]; and the Indians, a team put together by Andy Paull and featuring top players from the Squamish, Caughnawaga, and Onondaga tribes.[v]

Not surprisingly, the Canadian Lacrosse Association did not appreciate the wholesale raid of talent from the north, and promptly suspended everyone who signed to play in the new league.[vi]

Why were these Canadian stars willing to face suspension to play in a league in the United States? Money—specifically, money during the Great Depression. Perhaps recognizing this reality, the British Columbia Lacrosse Association gave permission for its athletes to play in the professional league; the CLA was not so understanding.

New Westminster star Jack Hughes, slated to suit up for the Canucks, fired back at CLA officials, stating “I can’t live on air,” and adding:

Don’t you realize, gentlemen, I’ll be out of work for a period of six or seven months and no money coming in. It’s swell for you fellows to have nice, cushy jobs; you can afford to sit back and say don’t go away [to the United States for the winter] or you’ll be suspended. It’s just like dealing with a cop; you always come off second best.[vii]

Lloyd Steele also challenged the CLA’s business in the matter:

You’re holding a gun to our heads and you’ll pull the trigger in the form of a two-year suspension when we get home. The commission governs us here in the summer. We can’t play for the teams we want to in the summer. Why try to govern us between seasons. It’s silly little rulings like this that ruin the game.[viii]

Ultimately, the lure of a paycheck trumped the threat of suspension, and a number of Canadian players headed south for the winter.

The season

Upon arriving in California, all four teams gathered at Echo Park Playground in Los Angeles to get ready for the opening of the season.[ix]

Each team played with sevenon the floor instead of six—if you’re thinking “but isn’t boxla just like hockey,” recall that a seventh man (the “rover”) was a fixture in Western Canadian hockey for years, and bled over into box lacrosse—and periods were 12-minutes long instead of 15. In addition, there was a faceoff after each goal—a startling innovation at the time.

League play began on January 8, with doubleheaders starting at 8:00 p.m. There was genuine enthusiasm for the sport, particularly among the Hollywood cognoscenti, with Bing Crosby set to serve as honorary referee on opening night.[x]

Those doubleheaders—held on Thursdays and Sundays—would be held at Los Angeles’ famed Grand Olympic Auditorium, the largest indoor arena in the world when it was built in 1924.[xi] Seating 15,300, the Olympic had hosted a number of high profile boxing matches over the years. Located just south of the Santa Monica Freeway at 1801 South Grand Avenue, the Olympic was a place to see…and be seen at. Famed author Charles Bukowski wrote:

…even the Hollywood (Legion Stadium) boys knew the action was at the Olympic. Raft came, and the others, and all the starlets, hugging those front row seats. The gallery boys went ape and the fighters fought like fighters and the place was blue with cigar smoke, and how we screamed, baby baby, and threw money and drank our whiskey, and when it was over, there was the drive in, the old lovebed with our dyed and vicious women. You slammed it home, then slept like a drunk angel.[xii]

As with the American League of 1932—and would be repeated with pretty much every incarnation of pro box lacrosse since—the press tended to focus on the violence in the game. “This is something like legalized mayhem, except that the players have to hit each other with sticks instead of their fists,” reported an anonymous Los Angeles Times scribe on game day, “but you have to see the game to appreciate it, so try and get out to the Olympic tonight for the massacre.”[xiii]

Over 4,000 patrons—including movie stars such as George Raft and Boris Karloff—entered the auditorium to watch the Hollywood Terriers defeat the Canucks, 19-12 in the opener, followed by the Los Angeles Yankees beating the Indians, 23-16. Fan consensus was that box lacrosse was the roughest game they had ever seen. Offered one Times pundit, “Here in the West they just call it ‘unlicensed murder.’”[xiv] Another said that fans “who like their football rough, their wrestling wild and wooly, their basketball fast and their ice hockey highly competitive will fall in love with [box] lacrosse.”[xv]

More than a few southern Californians did. Crowds hovered in the 4,500 range in subsequent weeks, and every week the second match on Sundays was broadcast live on KFAC, going up against the evening news and Amos ‘n’ Andy.

These new lacrosse fans could have their choice of heroes. Alf “Dynamite” Davey was tiny at 133 pounds, but was a scoring dynamo with the Yankees. Red-headed “Shipwreck” Kelly was the hard-checking centerman for the Terriers, and Garnie Carter turned heads with his play with the Canucks.

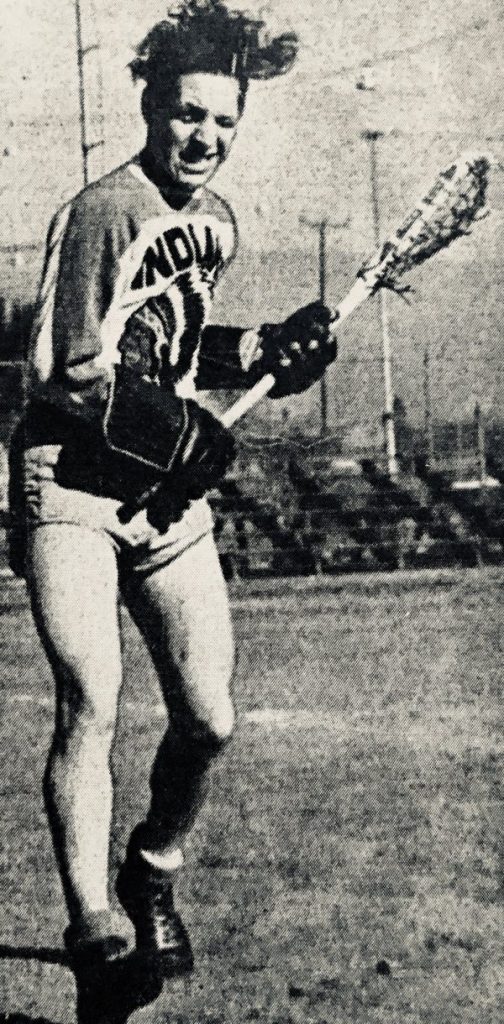

Then there was Harry Smith, the lightning-paced winger with the Indians. After scoring four goals against the Yankees in the opener, Smith would be a bright spot for the squad, which struggled in the PCLA, not winning their first game until January 19. Smith—nicknamed “Silverheels” because of his blinding speed—added a hat trick in the next match, a second win for the Indians.

The end

By the end of January, the Terriers were at the top of the table with a 6-1 record, followed by the Canucks at 4-3 and the Yankees and Indians at 2-5. Only 2,500 attended the January 29 games, however, and trouble was brewing in the league.[xvi]

The next day, the PCLA announced that it was dissolving. The reason given was not lack of funds, but issues with the Olympic Arena. League officials declared that the Olympic was unsuitable because of the seating facilities and the high overhead—rent was high, and only filling 4,000 of the just over 15,000 available seats could not have been a money-making proposition.[xvii]

Nevertheless, enthusiasm for the league was high enough that the Association initially announced it would resume play after securing an outdoor location (specifically, a softball park in Hollywood) where a box rink would be erected, a la the American Box Lacrosse League of 1932.[xviii] However, this never came to pass.

Even so, only two of the four teams were committed to continuing: the Los Angeles Yankees and Canucks. Plans were to have the two teams play a series of exhibitions which would be filmed by Pete Smith of MGM fame for a sports feature.[xix] Unfortunately, if this feature was ever made, it has been lost to time.[xx]

Of the other two teams, the Terriers returned to Ontario, although not to open arms—many had to serve the two-year suspension imposed upon them for bolting to the PCLA in the first place. The suspended players had a backup plan, though: Gunn announced plans to form a professional league in British Columbia.[xxi] In fact, in March 1939 it was reported that a circuit featuring teams from Seattle, Vancouver, New Westminster, and a Vancouver Indian team had been organized.[xxii] This attempt was subsequently abandoned, perhaps because the CLA lifted the suspensions on June 15, 1939.[xxiii]

The Indians also returned home—except for Harry Smith, who, for the previous two years, had been performing bit parts in movies at the suggestion of famed comedian (and avid lacrosse fan) Joe E. Brown. He remained in southern California and, over the years, he appeared alongside Humphrey Bogart in Key Largo; Maureen O’Hara is War Arrow; Glenn Ford in Lust for Gold; and Bob Hope in Alias Jesse James. In 1949, Smith landed his signature role: playing Tonto in The Lone Ranger television series and subsequent films. His stage name was taken from the epithet he was given for his lacrosse play: Jay Silverheels.

In less than ten years, three professional box lacrosse leagues had been tried in the U.S., and two had collapsed within a month. It would be almost another 30 years before there would be another attempt. By then, however, the Great American Sports Explosion made an attempt viable.

FINAL STANDINGS

| W | L | T | TP | GF | GA | |

| Hollywood Terriers | 6 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 113 | 93 |

| Canucks | 4 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 124 | 104 |

| Los Angeles Yankees | 2 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 116 | 135 |

| Indians | 2 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 105 | 126 |

[i] “Lacrosse Teams Fair Attraction,” Oakland Tribune, December 25, 1938

[ii] “Box Lacrosse Team Named ‘Yankees’,” Los Angeles Times, December 25, 1938

[iii] “Lacrosse Champions to Perform Here,” Los Angeles Times, December 30, 1938

[iv] “Lacrosse Squad Checks in Monday,” Los Angeles Times, December 31, 1938

[v] “Lacrosse Stars Gather Here; Teams Clash Soon in Big Carnival,” Los Angeles Times, January 1, 1939

[vi] “B.C. Boxla Men Start Long Trek Into California,” Nanaimo Daily News, January 1, 1939

[vii] Shillington, Stan, “Lights, Camera, Action!” https://bclaregistration.com/general/memory-lane/lights-camera-action.cfm (retrieved November 22, 2018)

[viii] Id.

[ix] “Lacrosse Foes Hold Workout,” Los Angeles Times, January 5, 1939

[x] “Fastest Players To Start For Yank Lacrosse Club,” Los Angeles Times, January 6, 1939

[xi] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Olympic_Auditorium (retrieved November 22, 2018)

The Olympic is still in use today, serving as a place of worship for the Glory Church of Jesus Christ.

[xii] Bukowski, Charles, “Goodbye Watson,” from Erections, Ejaculations, Exhibitions, and General Tales of Ordinary Madness (City Lights Books, San Francisco, 1982), p. 315

[xiii] “Box Lacrosse,” Los Angeles Times, January 8, 1939

[xiv] “Terrier, Yank Teams Win Box Lacrosse,” Los Angeles Times, January 1, 1939

[xv] “Double-Header For Lacrosse Fans At Olympic Tonight,” Los Angeles Times, January 15, 1939

[xvi] Somewhat ironically, this disappointing crowd occurred on a “Canadian Night,” when 275 sailors from the HMS Ottawa were honored. “Lacrosse Rivals to Honor Canadians at Olympic,” Los Angeles Times, January 29, 1939

[xvii] “Box Lacrosse Tilts Dropped,” Los Angeles Times, January 31, 1939

[xviii] Id.

[xix] Id.

[xx] A Library of Congress search did not reveal any evidence of the film being made.

[xxi] “Boxla League In California Thing Of Past,” Nanaimo Daily News, January 31, 1939

[xxii] “Box Lacrosse League,” Los Angeles Times, March 19, 1939

[xxiii] Shillington