John Davis has done a lot for lacrosse — now it’s lacrosse’s turn to do a lot for him... BY ROY MacGREGOR

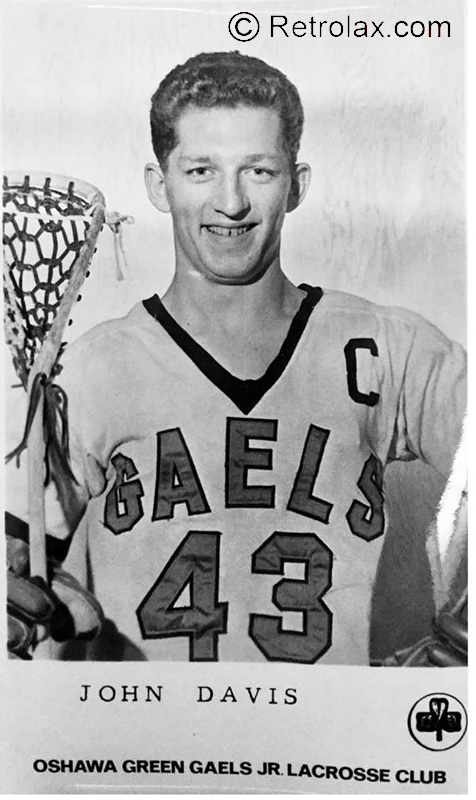

Certain things they held in common. Both came from small Ontario centres, one from Parry Sound, the other from Peterborough. Both came as teenagers to Oshawa. Ont., where each was the very best at his sport, one at hockey, the other at lacrosse; and they were stars in the same arena, one all winter, the other all summer. Both were the best known young men in town. For three years, 1963 through 1965, they shared equally the glory that was Oshawa.

Each dreamed that one day he would be at the top. not just the best in Oshawa. and since the boys played different games, there was room for both dreams to come true, and they did. The truth that was in the dreams, however, was not the same: for one it was better than expected, for the other it was what he expected — nothing.

The hockey player, Bobby Orr, traded Oshawa for Boston and the world, traded the $60-a-week junior hockey stipend for the untold millions that his game and advertising will ultimately bring him. The lacrosse player. John Davis, did some trading as well: one town for another. He went home to Peterborough. There was nowhere else to go.

Right from age 6, when Davis first played lacrosse, he’d been the finest of his age group. In towns like Whitby and Hastings, and in small cities like Peterborough and Oshawa he got his picture in store windows and never paid for his own coffee. Not much else. While Orr collected his $60 a week, Davis never received a penny. Davis left school early, as did Orr. but Davis barely got out of grade 9, which left him with nothing but his hopes.

“I had my dreams like anyone else,” he remembers of those years in Oshawa. when he starred for the Canadian champion Green Gaels. “Orr and I knew each other, and I could see what was happening to him, and I’d dream that it was lacrosse, not hockey, and me, not him. I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t so.”

Anything lacrosse in Oshawa ever returned to Davis came out of his own ingenuity. One season he bought dozens of white running-shoe laces, worked evenings writing his name in ballpoint on each lace, and had his fan club sell them to local girls to wear in their own sneakers. In one seven-game stretch he sold 160 pairs, netting some $20 profit. “I used to think my eyes would about pop out, writing on those thin laces, trying to hold them steady. I only kept it up because my name was short — thank God for that.”

Aware that he’d never make a living out of shoelaces, Davis worked the General Motors assembly line, and in 1966, when he went back home to Peterborough to play senior lacrosse, he got work in the stockroom at Outboard Marine, moving on later to selling cars and finally landing a job he stuck with, clerking in a sporting goods store owned by two of his teammates. The hometown team came up with some money, too, $8 a game to begin with, rising later to $14. But it hardly helped, any more than the baby bonus did, with the raising of three boys. In all his years, from 6 through 31, which he is now. Davis was top scorer for his team. Only a half dozen times did he fail to be top scorer for his league; then he was usually second. For most of that quarter century of lacrosse he received next to nothing.

To understand why a boy and then a man would continue down such a road, all the time knowing the bridge at the end was washed out, you have to first see and understand the small-town athlete. He plays, and continues to play, because the ethos demands it: he is not just himself, he is also the town, and he is not playing a game, he is defending the town’s honor. There is no winner like a small-town champion — the free beers, the waves, good car deals, hero worship from the children — nor is there a bum like a small-town loser. But it is because they all imagine themselves winners that they keep at it, usually far too long for their own good. They see nothing but glory to come, a nd it is this promised glory that is at the roots of the small-town hero’s set of values.

All that time Davis clung to his crazy dream that even if he didn’t have the chances Orr got, at least lacrosse would one day pay him back. In 1968 he actually thought it was going to happen. The National Lacrosse Association (NLA) was formed and Peterborough, along with such larger centres as Montreal and Toronto, received a franchise. Unfortunately, the league went broke almost immediately, and the Peterborough team, which had been one of the more suecessful, dropped $30,000. Davis, who had received $50 a game for the season, found out the next year, when Peterborough went back to senior status, that there was not even enough money to pay him $14 a game, it I seemed then that his one chance had come and gone.

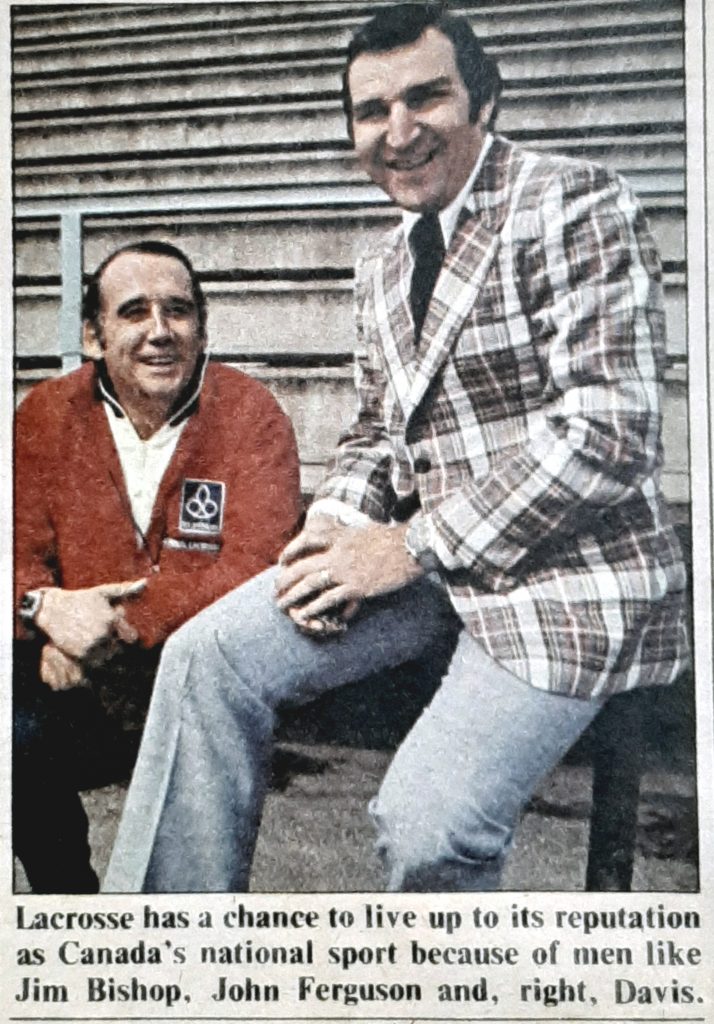

But last year came a second chance. Somehow, the indoor style of box lacrosse played in Canada got big money backing and launched an all-out campaign to sell itself as a big-league indoor sport, mainly in the United States where field lacrosse (played outdoors) has long been popular. With big name promoters like John Ferguson and financiers like Bruce Norris,franchises were established in Philadelphia, Syracuse, Rochester and Maryland, as well as in two Canadian cities, Montreal and Toronto. They called it the National Lacrosse League to ensure no one thought of it as a revived NLA. In places like Philadelphia and Maryland, where they sold the violence of the game, it went over very well. In places like Toronto, where they sold it on corn ball ideas such as getting people to come out to support Canada’s national game — which it is by decree, but certainly not by faith — and where they had no air-conditioning in the arena, the game failed miserably.

Had the game also failed in Montreal, our national game would today be played professionally only in the U.S. And it should have failed there if it failed in Toronto, Ontario, after all, has a rich history of the game, and along with B.C. produces its best players. Quebec has a patchy tradition, and Montreal had been the biggest loser in the ill-fated 1968 attempt to professionalize lacrosse. Yet it caught and held. One reason would be the exciting play of the team’s first draft choice, John Davis, but the main reason is undoubtedly another John, the club’s president John Ferguson.

Ferguson succeeded because the people refused to let down the only English Canadian ever to attain folkhero status in French Canada. The people weren’t quick to forget the decade Fergie skated and slugged for the Montreal Canadiens (he retired in 1971). And there may even have been some who knew that John Ferguson had been a far better lacrosse player than hockey player and, had the money been there, would gladly have played the summer sport over the winter one. So if Fergie liked it, it must be good.

By the end of last summer, the Montreal Les Quebecois franchise was fairly solid. The Toronto franchise and two others were crumbling. Toronto was moved to Boston, Rochester to Long Island, and when the time came to move the Syracuse franchise, i someone suggested Quebec Cty: if it would work in one French community it could work in another. And there was another element that lacrosse people knew would also help — the rivalry between Quebec Cty and Montreal, the intense hatred that is, in fact, the essential reason why lacrosse has always been a successful small-town sport in Canada.

By the early stages of the NLL’s second season it had begun to look less like an illusion to Davis. There was already league talk of expansion and TV contracts. As for Davis, he was off to the very best start of his playing career and his own teamwas keeping near the top of the league, and both were probably due to the coaching of Jim Bishop, the controversial executive of the Detroit Red Wings hockey club who is also recognized as the most successful coach in lacrosse.

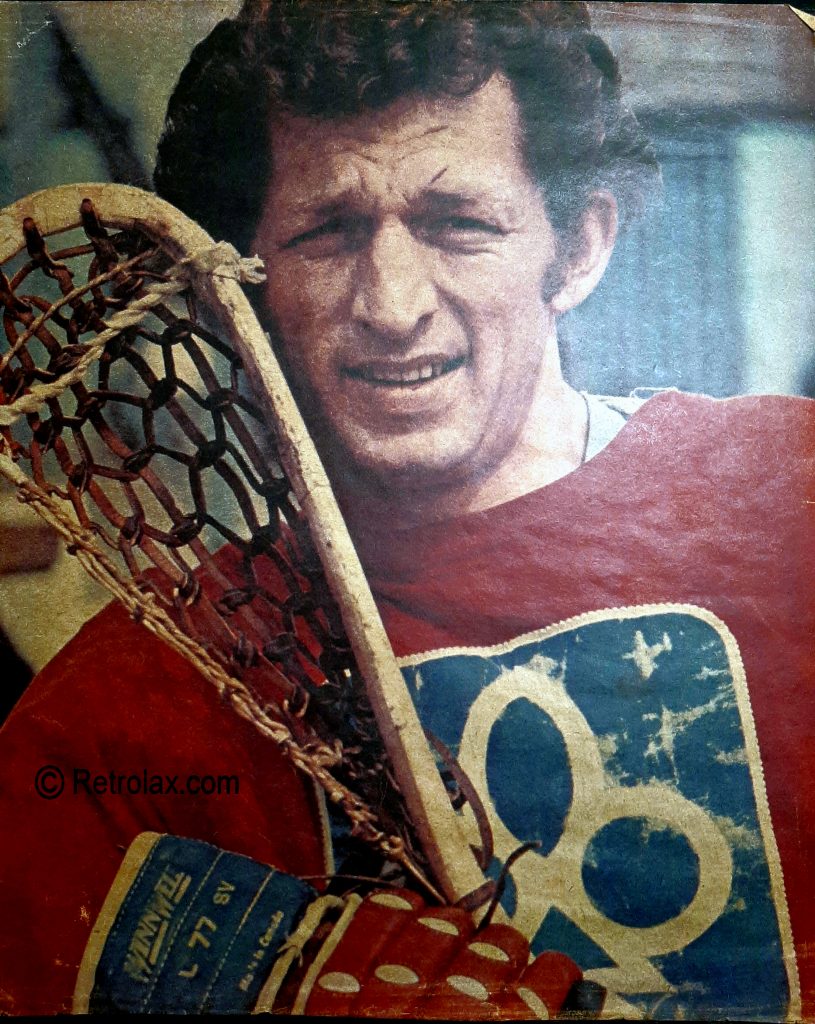

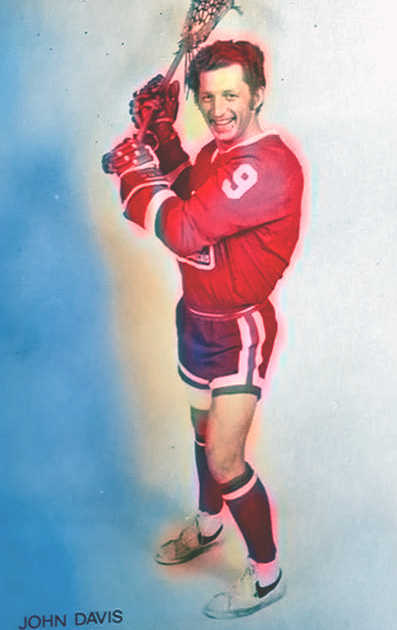

Davis’ salary had been hiked to around $15,000 per season, one of the highest in the league, and the team had also given him an off-season job, promoting Les Quebecois around the city. For the first time, he was going to work in suits. And even though he was 31, he was still at the top of his league. He was playing for money as well as he had played in all those younger years when he’d been a star for nothing. He looked, as a pro, much as he had looked even when he played in Oshawa, far smaller than you’d expect, with closely cropped hair on the sides that rises high, blonde and curly on top, combed straight back. He appears somewhat out of time, as if plucked from an old regiment photograph from the Second World War. Like the soldiers, his look is open, shy, full of hope and very rural. Like them, too, he feels he’s setting out on an adventure.

Outside the Quebec City Coliseum there are four figures cast in concrete, each representing a sport — boxing, figure skating, hockey and lacrosse. The arena is a quarter of a century old, and a great many of the people arriving this evening have no idea why the lacrosse player was ever cast. The older ones know, though, and can still remember the glory years of lacrosse in Quebec City, when Punch Imlach coached the game and Jacques Plante was a hotshot young goaltender.

John Ferguson, in a tailored blue and white sports jacket, leaned one meaty hand on the wall of the exit behind his team’s bench. “You know, it’s a funny thing. I played my first pro hockey game in this arena. And I can still remember getting out of the car in the parking lot, looking up and what’s the first thing I see? — that cement hockey player. And I wished I was coming to play lacrosse. I’d like to have played lacrosse here. The French used to love this game, you know. And they’ll love it again.”

The more than 6,000 who showed up this night loved it. The script was perfect. Ferguson was there acting in a manner wholly unbecoming to a team president,’ cursing the referees, advising his Montreal team who they should hit, signing a continuous daisy chain of autograph books. There was a first-period fight, won by Quebec. There was a 10-4 hometown lead that dwindled steadily until Montreal’s Michel Blanchard, who is thought of as The Great French Hope in lacrosse, tied it up with two minutes remaining, only to have the home town steal victory in the dying seconds. Quebec City won this battle, but there would be other meetings between the two, all played in the same essential atmosphere of hatred, the atmosphere that’lacrosse breathes best. You got the feeling that night that Quebec City and Montreal had long been waiting for the day when they would have professional teams competing in the same league.

The game had long since ended. The bus had slipped quietly, through the starlit Quebec night into Montreal. Il had emptied as it had come, quietly, and most of the losers went sadly home.

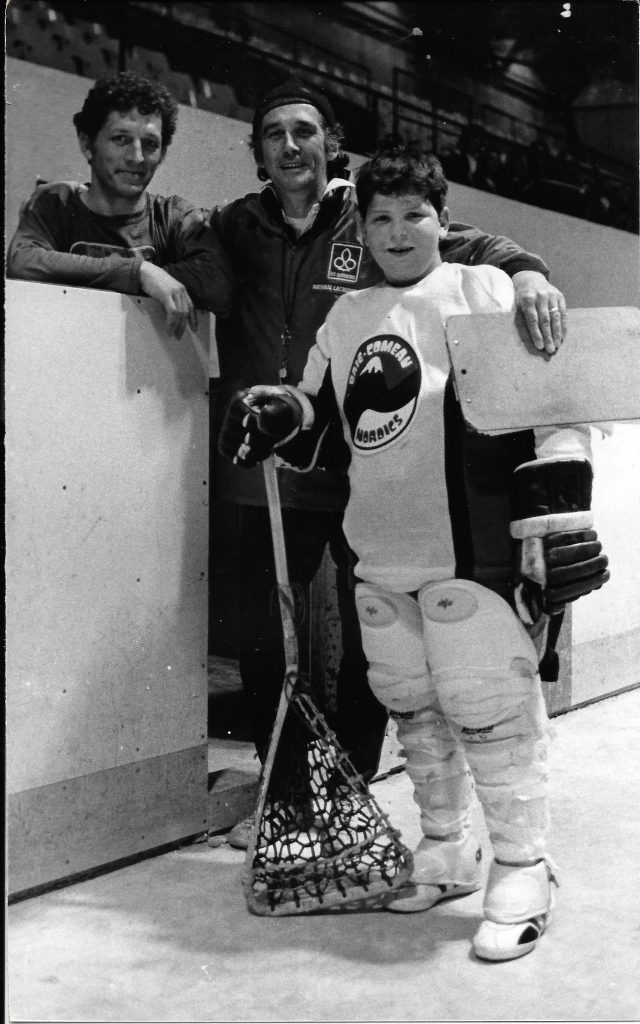

Later, on St. James West, John Davis sat sipping a beer in the South Seas Chinese restaurant. To the east the Montreal skyline was pinking over. It was dawn. He had sat there all through the night. It was his privilege, one of his new ones — just as they now hang his picture in the restaurant. The manager is a lacrosse nut the way other Montrealers pray to hockey. Davis sits there talking about his coach, Jim Bishop, whose insistence on fitness has put Davis into the best shape of his career. Bishop, 46, has probably the best record of any coach in Canadian history, having one time acquired 19 championships in 19 seasons, and in the mid-1960s he took his Oshawa Green Gaels to seven consecutive Canadian junior championships (of which Davis played for three). We are talking about

insistence on fitness has put Davis into the best shape of his career. Bishop, 46, has probably the best record of any coach in Canadian history, having one time acquired 19 championships in 19 seasons, and in the mid-1960s he took his Oshawa Green Gaels to seven consecutive Canadian junior championships (of which Davis played for three). We are talking about how it’s sometimes difficult to embrace the Bishop philosophies (he will, for instance, say things like “If you’re going to be an open-heart surgeon, do you have any right to be anything but the best?” and expect you to apply it to lacrosse). But it works. I can personally attest to it, having played several years ago for one of Bishop’s provincial champion teams, and 1 still have memories of 12- and 13-year-old kids being pushed to the point where they would actually vomit over the boards. But, as Davis and I agree, it works and works well. And he, at the tail end of his career, is thankful Bishop is there at this time. If anyone can give him a longer lacrosse life. Bishop can.

“Maybe I’ve got five years left, that’s all. My days are numbered and I know it. But just maybe before these five years are up lacrosse will break through and I’ll make 40, maybe 50 thousand out of it. And maybe my three boys will.get something out of the game. ” I’m just glad it didn’t completely pass me by. I’ve dreamt of this ever since I started playing. . . .”

It is the little things that have told him the dream is here finally. Little things like the standing ovation he received last year when he hit the 50-goal mark (he ended up with 78), and little things like the afternoon before when he’d been waiting for the team bus and a truck had pulled up alongside him: the fat, baldish driver had stared a moment, smiled and saluted. The recognition is coming, slow but sure, and John Davis has been waiting as long as he cares to.

“You know, it’s hard to believe it now,’’ he says taking another swig from his beer. “But I actually used to pray for rain when I sold laces back in Oshawa. Rain made the ink run. Then they’d have to buy replacements.”