by Steve Holroyd (laxmavn@aol.com)

Notwithstanding the failure of the National Lacrosse Association in 1968, and the similar failure of the Western Lacrosse Association and Eastern Professional Lacrosse League the following year, Jim Bishop remained committed to his dream of making box lacrosse a viable professional sport.

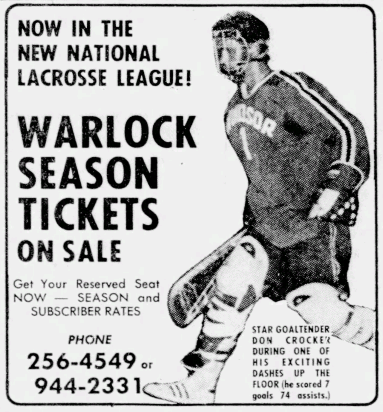

Even after Bishop’s fine work with the NLA’s Detroit Olympics landed him a job as an executive with that team’s parent organization, the National Hockey League’s Detroit Red Wings, he continued to coach box lacrosse teams. His Windsor Warlocks were Canadian Lacrosse Association Senior B champions in 1970 and 1971.

Bishop had a storied career in the game—prior to the Warlocks, he had founded the Oshawa Green Gaels in 1946, turning them into a national power in junior lacrosse, with seven consecutive Minto Cup wins from 1963 to 1969. No, success was no stranger to Bishop. Still, he longed for more.

Thus, in November 1971, Bishop announced plans for a “super” lacrosse league, consisting of top teams in Ontario and British Columbia. Bishop’s new league would include an eastern division, and a western division made up of teams from the Western Lacrosse Association’s Senior A League—Vancouver, Victoria, New Westminster, and Coquitlam. Plans further called for separate standings and playoffs for each division, with a 30- to 32-game schedule, including interlocking games between the two divisions, a format not unlike that being employed by the Canadian Football League at the time.

Unlike with the NLA, however, this new league would be semi-professional at first. “In a truly professional league, the players don’t have to work as well as play. Obviously, our players will have to work,” explained Bishop. However, Bishop made it clear that full professionalism was the league’s ultimate goal: “It has to come whether it takes three years, four years of whatever. To say professional lacrosse failed before is being negative. The product is there, it has just never been presented properly.”[1]

As to the product, a salary limit of $25 per game was set for players.[2] As far as presentation, Bishop reported that the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation had a proposal to offer a national television package involving prime time broadcasts. Bishop hoped that a CBC broadcasting deal, along with sponsorship from a major tobacco firm, would help provide some of the start-up costs.

Finally, Bishop explained that the league would work in cooperation with the Ontario Lacrosse Association and Canadian Lacrosse Association, but would employ its own owners’ council and commissioner.[3]

Birthing pains

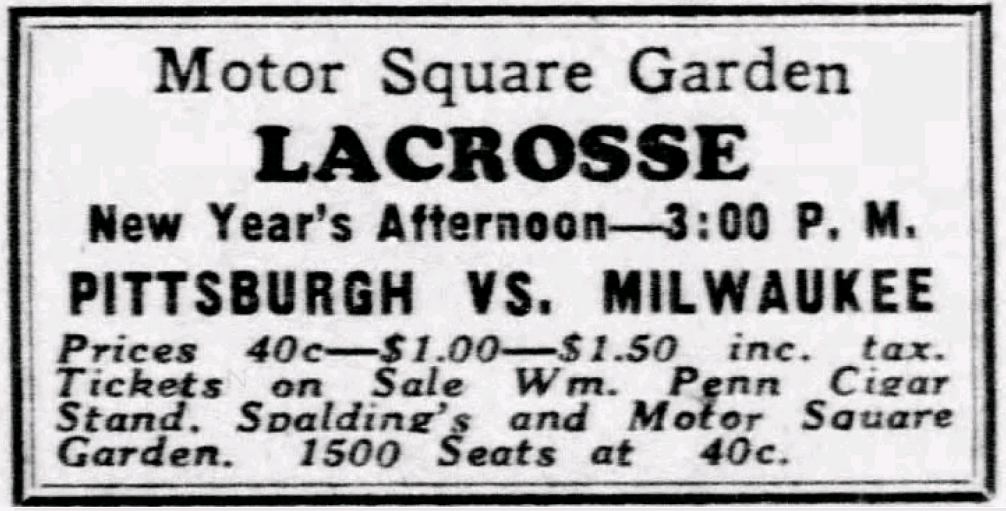

As the Western Lacrosse Association was well-established—all of its teams had played professionally in the NLA in 1968, and operated as “professional” in 1969—Bishop’s proposed new league had the Pacific coast covered. The east, however, proved to be a more difficult task. Seven cities initially expressed interest in the new circuit—Toronto, Peterborough, Windsor, Brantford, Aurora, Oshawa, and Brampton—and the rubber was to meet the road at a meeting on December 1 at the Seaway Beverley Hills Hotel in Toronto, when franchises would be expected to post a $10,000 performance bond. At the meeting, however, only Bishop’s Windsor Warlocks, Peterborough Lakers, and defending Mann Cup champions Brantford Warriors posted a bond—even after it had been reduced to $5,000. Apparently, an Aurora group was willing, but lacked both financial backing and a suitable building for the project.

Bishop and Brantford coach Morley Kells—like Bishop, a key figure in the NLA—endeavored to find a fourth team for the east. “I’m not going to let this thing die now,” said Bishop. “I think we all realize that this is a last-ditch effort to save the image of major lacrosse in Eastern Canada. If we have to go into a town and finance a franchise ourselves or with financial help from the [Ontario Lacrosse Association], we will do it.”[4]

Kells’ boss, Brantford president Keith Martin, had no intention of helping to finance a fourth team, however. “Regardless of what people think of our financial status, we are not that well off. We have enough trouble putting our own package together. As far as we’re concerned, if a fourth team cannot be found which will finance itself, the league is off.”[5]

Options for a fourth team included relocating the Aurora group to Orillia or Kitchener, or placing a team in Rochester, Syracuse, Flint (Michigan), Ottawa, Cornwall, Barrie, Owen Sound, or Collingwood.

In reality, though, any hope for a professional, “major” league would require a Toronto franchise. By early January, a group to back a franchise—the Toronto Shooting Stars—had been secured.

While the western teams’ rosters were already established, the eastern teams—one of whom (Toronto) was brand new, while another (Windsor) had only operated at Senior B—needed a draft to fill out their rosters. This draft was held on January 29, with each team drafting 35 players while protecting 14 players each. In the case of Toronto and Windsor, the protected lists consisted of desired players on other teams. For instance, Bishop’s Warlocks selections were a combination of players who had starred for his Senior B champions, along with a number of individuals who had played for his Green Gales and Detroit Olympics sides.

The new league—dubbed the National Lacrosse League—appointed Canadian Lacrosse Association second vice-president Gord Hammond as commissioner.

Unfortunately, the “national” part of the National Lacrosse League received a body-blow in early February 1972, when the WLA teams rejected a fully-interlocking schedule as being not economically feasible. Instead, NLL Commissioner Hammond and WLA Commissioner Tom English agreed to a partial interlocking schedule, whereby two touring teams from the west would play one game each against the four Ontario Lacrosse Association teams, while two teams from the east would go west and do the same against WLA sides. Both leagues anticipated an entirely integrated schedule “in a few years.”[6]

The result of interlocking games played in the east would count in the Eastern Division standings, but not in the WLA’s. Similarly, the games played by the two eastern teams out west would not count in the standings—in this way, balanced schedules in the two leagues would be maintained.

What was the “National Lacrosse League”?

The lack of a fully-integrated locking schedule was not the only blow to Bishop’s plans. The WLA—having already suffered through professionalism as the Western Division of the NLA, and as an independent league the following year—was in no hurry to start paying players again. “[T]he close-knit, four-team loop enjoyed considerable financial success last year. They were in no rush to disturb mining that gold to entertain some speculative digging in new fields.”[7]

As a result, 1972 was simply business as usual for the western league; other than hosting two eastern teams, and having two teams make a trip east, nothing would be different.[8]

The east, however, would play as “professional,” even if, in reality, it was a semi-professional circuit at best.

In the east, the Ontario teams were typically referred to as the Eastern Division of the NLL, while standings published in papers like the Windsor Star listed the circuit as “National Lacrosse League”; out west, when the NLL was mentioned at all it was often referred to as the “Ontario Lacrosse Association” or “Eastern Lacrosse Association,” perhaps to emphasize that the NLL was actually a loose confederation between the long-established WLA and its eastern counterpart. Western papers did use “NLL,” but only when describing the interlocking games.

(Because the WLA was, for all intents and purposes, still operating as an amateur circuit, this article will focus on the “professional” aspects of the NLL: the Eastern Division, and the interlocking games.)

Eastern Division

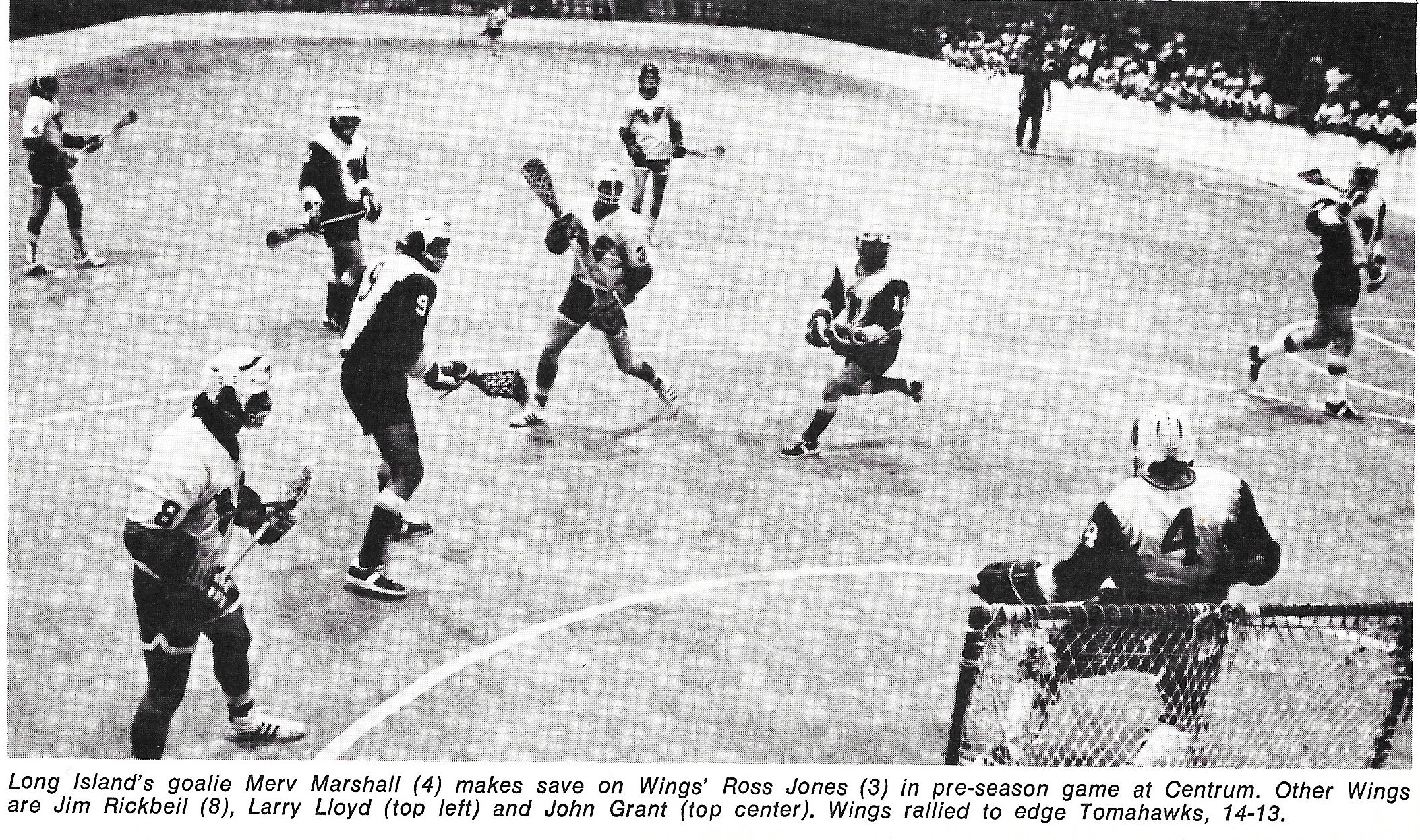

The four Ontario teams dutifully put together their 23-man rosters for the season. The teams would make up a mix of players who had starred in the NLA in 1968, and would go on to star in the second version of the NLL, in 1974-75.

The NLL opened play on May 4, with Brantford Warriors defeating Peterborough Lakers, 20-16 in Peterborough. Gaylord Powless scored five goals for the winners, while Wayne Grainger and Bill Coghill added hat tricks. John Davis scored four for the Lakers, while Joe Todd and Cy Coombes scored three each for the losers.

Not surprisingly, the prospect of $25 per game did not result in an exodus of players from the WLA. The only major defector was Bill Bradley, who jumped from Coquitlam Adanacs to join Bishop’s Warlocks. Coming off an impressive 117 point season in 1971, Bradley was expected to give Windsor some experience and scoring punch as it made the jump from Senior B to professional. Unfortunately, the 32-year old Bradley got off the a slow start with the Warlocks, first battling food poisoning and then suffering a broken jaw during a game on June 12. Adding insult to injury, Bradley was the victim of mistaken identity. “Powless (Brantford Warriors’ Gaylord) was hit pretty hard by somebody,” Bradley explained. “(Ron) McNeil thought I did it, and said he was going to get me.” McNeil ran Bradley down from behind late in the game, and Bradley sustained the injury. Bradley was sanguine about it, however: “You can’t let something like that bother you, or you shouldn’t be playing.”[9] Bradley would eventually turn in a solid campaign, scoring 36 goals and 85 points in 30 games.

Nevertheless, Windsor struggled. There was a big difference between Senior B and professional, and—notwithstanding complementing stars from the two-time Senior B champions like Merv Marshall, Don Crocker, Jim Hinkson and Thom Vann with veterans like Bradley and new stars like Jim Higgs—the Warlocks were plagued by inconsistency all season long.

No small amount of blame was directed at Bishop. Given his remarkable success at the junior level, one could understand why Bishop was fully committed to his system—a high-press, up-tempo style of play that owed a lot to basketball strategies. However, it became clear to observers that the 1972 Warlocks were a team too committed to the system—and that Bishop had grown too in love with his own style to appreciate that he was holding his players back. “They’re a machine out there and he’s the control box,” offered Ron Liscombe, who began the year under Bishop before being traded to Peterborough in July. “If one object in that machine isn’t working, he replaces that object. I wasn’t playing my game [in Windsor]; I had no freedom. I could go for periods playing well, then have a bad period and I’d be on the bench. It got so every time I went out on the floor, I’d be thinking of making a mistake.”[10]

While it might be easy to dismiss the criticism as merely the sour grapes of a discarded player, the media was inclined to agree. “In their loose ball pursuit, their passing, their catching and their shooting, Warlocks have often resembled men playing in straight jackets,” wrote beat reporter Alan Halberstadt. “To question the techniques of a coach as successful as Bishop might be heresy but then again Bishop has only coached once before in the best lacrosse league in the country. That was 1968 with the Detroit Olympics and Bishop didn’t win.”[11]

For all of Windsor’s issues, it was nothing compared to those suffered by the Toronto team. The NLL was counting on the Shooting Stars to make an impression in Canada’s leading market. Unfortunately, after winning their first two games, Toronto went on an unbearable 15-game losing streak. Recognizing that a competitive Toronto team was essential to the league’s growth and survival, the NLL held a special draft to allow the Shooting stars to bolster their lineup. Among the players obtained by Toronto was Earl MacNeil, who had not played a game with the Windsor Warlocks.

Toronto also obtained some less-conventional help in the form of super-fan Marianne Jespersen, who embarked on a pole-sitting campaign above Bloor Street in Toronto on June 23, resolving to stay there until the Shooting Stars won a game. Fortunately, she was only there four days before Toronto finally broke the streak, edging Windsor, 16-14.[12]

It also turned out that Bishop’s tactical abilities may not have been the only thing abandoning him in 1972; his ability to evaluate talent may have also been slipping. Earl MacNeil got off the Warlocks’ bench and proceeded to light the NLL on fire with Toronto, scoring 52 goals in 17 games—a remarkable 3.06 goals per game.[13] The Shooting Stars went a respectable 8-6-1 the rest of the season.

During the season, NLL Commissioner Gord Hammond stated that the league expected to expand in 1973, with plans to admit Ottawa, Montreal, and Buffalo. The reality, however, was that each of the four current teams was looking at closing the season with sizable deficits. Peterborough, with several home games drawing less than 1,000 people despite the fact the Lakers were one of the best teams in the league, announced that it would likely relocate to Ottawa for the 1973 season. Meanwhile, Windsor—whose arena was not ready in time for the start of the season and whose crowds were also disappointing—were exploring a move to Flint, Michigan for 1973.

Brantford Warriors won the regular season title, but not without some drama of its own. On June 19, Hammond suspended the entire team because the Warriors had used players who were under suspension in a game. Complicating matters was the fact that the suspension was levied just before Brantford was scheduled to begin its swing of games out west—where the Warriors, as defending Mann Cup champions, were sure to be a big draw. Later, only coach Morley Kells and general manager Bill Wallace were suspended, and served the suspensions until August 5, after the other three teams in the Eastern Division voted to reinstate them.

On a lighter note, Linda Shepley won the Miss National Lacrosse League beauty contest in Toronto. Previously winning the title of Miss Windsor Warlock, the Windsor native won the crown in competition with seven other girls “from cities where the NLL had teams.”[14]

The final regular season standings:[15]

| W | L | T | TP | GF | GA | |

| Brantford Warriors | 22 | 10 | 0 | 44 | 553 | 447 |

| Peterborough Lakers | 19 | 12 | 1 | 39 | 415 | 416 |

| Windsor Warlocks | 14 | 18 | 0 | 28 | 508 | 474 |

| Toronto Shooting Stars | 10 | 21 | 1 | 21 | 414 | 524 |

With only four teams, each were eligible for the playoffs. The top-seeded Warriors swept Toronto, and Peterborough took its series with Windsor in six games.

The Eastern Division finals were a classic series, with Brantford finally winning in 7 games.

Although only playing half a season with Toronto, the Shooting Stars Earl McNeil was named Most Valuable Player. The 24-year old was also named a first team all-star, along with Brantford Warriors Bob McCready (G), Paul Suggate (D), and Jerry McKenna (D); the other first team forwards were scoring champion Jim Higgs (Windsor) and John Davis (Peterborough). The second team: GOAL—Pat Baker (Peterborough); DEFENCE—Bill Bradley (Windsor), Carm Collins (Peterborough); FORWARD—Gaylord Powless (Brantford), John MacDonald (Windsor), Ron MacNeil (Brantford—and older brother of Earl).

Toronto’s Bill Sheehan, with 56 goals, was named Rookie of the Year. McKenna was named defenceman of the year, and Peterborough’s goaltending duo of Baker and Wayne Platt had the division’s best goals against record, with 415 in 32 games.

LEADING SCORERS (regular season):[16]

| NAME | TEAM | GP | G | A | TP |

| Jim Higgs | WIN | 32 | 54 | 99 | 153 |

| Paul Suggate | BRA | 31 | 58 | 85 | 143 |

| John MacDonald | WIN | 32 | 51 | 79 | 130 |

| John Davis | PTR | 29 | 61 | 67 | 128 |

| Gaylord Powless | BRA | 29 | 47 | 79 | 126 |

| Brian Wilson | BRA | 27 | 58 | 52 | 110 |

| Larry Lloyd | WIN | 31 | 59 | 48 | 107 |

| Bill Coghill | BRA | 28 | 56 | 45 | 101 |

| Ron MacNeil | BRA | 23 | 60 | 40 | 100 |

| Bill Sheehan | TOR | 31 | 56 | 38 | 94 |

| Cy Coombes | PTR | 31 | 66 | 23 | 89 |

The “National Lacrosse League”

While the concept of a “professionally run” league in the east was important, the idea of a truly national lacrosse league was of much more interest to lacrosse aficionados. Thus, the interlocking schedule—even watered down from its original concept—was eagerly awaited.[17]

Windsor and Brantford committed to making the trip west, each playing four games against the WLA teams with a guaranteed $8,000 each for expenses. New Westminster Salmonbellies and Vancouver Burrards would venture east; those teams received $10,000 each, the difference being additional travel required by the western teams.[18]

As Brantford were defending Mann Cup champions, interest in that club in British Columbia was high. A record crowd of 7,492 turned up at Pacific Coliseum on July 11 to watch the Warriors defeat the hometown Burrards, 14-9. The games in the western were generally well-attended.

Crowds back east were less impressive. Only about 1,700 turned up for a game between Vancouver and the Toronto Shooting Stars. However, it should be noted that Varsity Arena in Toronto did not have air conditioning, and the temperatures were in the 80s that week of July.

Even bearing in mind that the touring teams could afford to take the games easy because the games did not count in their standings, the interlocking series was pretty competitive.

“NLL” Standings:[19]

| GP | W | L | T | Pct | GF | GA | |

| Victoria Shamrocks | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1.000 | 32 | 44 |

| Toronto Shooting Stars | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1.000 | 24 | 18 |

| N. Westiminster Salmonbellies | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0.714 | 88 | 76 |

| Brantford Warriors | 7 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0.571 | 111 | 101 |

| Peterborough Lakers | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.500 | 22 | 23 |

| Windsor Warlocks | 6 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0.333 | 81 | 81 |

| Vancouver Burrards | 6 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0.167 | 68 | 92 |

| Coquitlam Adanacs | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.000 | 35 | 48 |

“World Series”

Unlike in 1969, the champions of the Eastern and Western Divisions did not face off in a separate national finals series. Instead, it was agreed that the respective winners in 1972 faced off in the Mann Cup finals.[20] The series was a repeat of the 1971 Mann Cup, with Brantford Warriors defending their title against the New Westminster Salmonbellies. Salmonbellies won the title in a sweep by scores of 13-8, 13-11, 20-9, and 18-16.[21]

The end

Back in November, Bishop had stated that an average attendance of 2,000 or better would be required to attain financial solvency. In Windsor, he fell short of that mark—which meant problems were setting in.

Averaging about 1,500 for the season, the Warlocks took a beating financially. “It hurt when we lost to Peterborough (in the division semi-finals),” said Dick Dinnes, an executive director of the Windsor franchise. “We may have broken even, or at least approached that mark, in a series against Brantford.”[22]

Not helping matters was the fact that neither the CBC television deal nor corporate sponsorship ever materialized.

The NLL also realized it had competitive issues that needed to be corrected in 1973, draft “equalization” issues among them. But finances remained the primary concern.

To that end, the league was looking for two changes in 1973. First would be a “five-year plan” from each franchise, reflecting a commitment to professionalism. A second was a rather forward-thinking concept: incorporating a separate entity called “National Lacrosse League Properties” which would be responsible for things such as programs for the teams, national advertising, and promotion.

In the end, it was all moot: in December, the Winsdor Warlocks withdrew from the league. Toronto soon followed after initially putting the team up for sale. Down to two teams, the eastern division of the NLL was defunct. As a result, so was the NLL concept itself. There was one last-ditch effort to preserve the NLL, even after it folded. Morley Kells offered to leave Brantford and take over the Toronto franchise, provided he could protect 10 players from the roster and take two Warriors (Ron MacNeil and Al Gordaneer) with him. Kells said he could secure new ownership under those conditions. He also suggested relocating Windsor to Oshawa, since most of the team was from that area. Finally, he indicated that there was interest from the Buffalo-St. Catherine’s area on a franchise.[23] Ultimately, there was too little interest in the concept. The NLL was dead. Instead, all of the Eastern Division teams except Windsor returned to a new concept, Ontario “Major Series” lacrosse, for 1973.

Bishop and Kells would not give up on pro lacrosse,

however. In less than two years, they

would both be on the ground floor of a new

National Lacrosse League—one which would have a much more lasting impact on the

sport.

[1] Halberstadt, Alan, “‘Super’ boxla loop in embryo stage,” Windsor Star, November 10, 1971

[2] By way of comparison: adjusting for inflation, $25 in January 1972 is worth $152.82 in December 2018 dollars. $25 in January 1972 was worth $67.64 in January 1987, when the Eagle League started (calculations via https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl)

[3] Halberstadt, “‘Super’ boxla loop….”

[4] Halberstadt, Alan, “Missing link in lacrosse plans,” Windsor Star, December 2, 1971

[5] Id.

[6] “National boxla league joins east and west,” Vancouver Sun, February 17, 1972

[7][7] Nelson, Jim, “Warlocks face new foes but west tests reduced,” Windsor Star, April 20, 1972

[8] Which is not to say the WLA was not anticipating a fully-integrated NLL sooner rather than later. In order to strengthen the weaker teams in the circuit, the WLA instituted its first common draft for juniors. “Boxla Draft for Juniors,” Nanaimo Daily News, April 19, 1972. In addition, the Vancouver Burrards also anticipated a future in a fully-integrated NLL, moving from Kerrisdale Arena (capacity: 3,000) and entering into a two-year agreement to play games at the Forum on the PNE grounds (capacity: 4,000) with games against the eastern teams held at the Pacific Coliseum (capacity: 15,000). Feser, Dennis, “Boxla Burrards move across town,” Vancouver Sun, April 13, 1972

[9] Feser, Dennis, “Bradley finds happiness as Warlock,” Vancouver Sun, July 26, 1972

[10] Halberstadt, Alan, Untitled Column, Windsor Star, August 18, 1972

[11] Id.

Halberstadt is being a bit unfair with his last point; Bishop’s Olympics won the NLA’s Eastern Division crown rather easily, and advanced to the league finals before losing to New Westminster, 4 games to 2.

[12] “Pole Sitter Off The Hook,” Nanaimo Daily News, June 28, 1972 (CP report)

[13] By way of comparison: 1974 NLL leading goal scorer Paul Suggate (Maryland Arrows) scored 115 goals in 40 games (2.875 per game). That same year, Rochester’s Rick Dudley—limited to only 28 games due to his NHL commitments with the Buffalo Sabres and various NLL suspensions, scored 81 goals (2.89 per game).

[14] Windsor Star, August 10, 1972. The fact that the WLA teams were apparently more committed to an integrated beauty contest than a full-national league is amusing.

[15] Stewart-Candy, Dave, Canadian Lacrosse Almanac (2019 edition)

[16] Compiled from the “Bible of Lacrosse” database, http://www.wampsbibleoflacrosse.com/newstats/players.txt

[17] Although apparently not so much that it warranted a mention in the 1972 WLA Yearbook—neither the NLL nor the interlocking schedule is referenced.

[18] “Warlocks to go west,” Windsor Star, April 11, 1972

[19] Stewart-Candy

[20] See Nelson, “Warlocks face new foes….”

[21] It should be noted that the fact Brantford was able to vie for the Mann Cup—a strictly amateur competition at the time (hence the need for a separate “world series” in 1969)—begs the question of whether the NLL was in fact “professional” or “semi-professional,” as opposed to being “professionally run.” Given numerous reports of the significant amounts of money lost by NLL teams, there is a strong inference that players were being paid. It is possible that, like the Olympics in later years, the amount earned per game was considered too de minimus to disqualify the NLL teams. Another thought: the CLA did not wish to water down the tournament by disqualifying the top eastern teams, including the defending champion, and was willing to look the other way during the NLL “experiment.”

[22] Nelson, Jim, Untitled Column, Windsor Star, October 27, 1972

[23] “Lacrosse Saviour Has Plan,” Victoria Times Colonist, December 20, 1972 (CP report)