by Steve Holroyd (laxmavn@aol.com)

Women’s lacrosse has been invited back to the World Games in 2021. The success of women’s lacrosse at the 2017 edition in Poland resulted in not just a return invite for the ladies, but also the inclusion of men’s lacrosse as an “invitational sport” at the 2021 games in Birmingham, Alabama (in addition, wheelchair lacrosse is also being added as an “invitational sport.”)

With the news came repeated calls for lacrosse to return to the Olympics as an official sport. While lacrosse has been contested in the summer games, it has not appeared in the Olympics since 1948—as a mere “demonstration sport”—and has not been an “official” sport at the Games since 1908.

With 41 countries playing in this summer’s FIL World Lacrosse Championships, and with an increased presence at the 2021 World Games, there is a feeling of inevitability that the Creator’s Game will return to the Olympics, sooner rather than later.

When that time comes, there should be renewed interest in the history of the sport at the Games. Fortunately, the sport’s appearances at the 1908, 1928, 1932, and 1948 editions of the Olympics are fairly well documented.

Its first appearance in 1904, on the other hand, is a bit of a mess.

Look at the official record, and you will find Canada won gold at the 1904 games, with the United States taking silver and Canada (again) taking bronze. You will also learn Canada Gold (actually Winnipeg Shamrocks) defeated the U.S. (actually the St. Louis Amateur Athletic Association) in a final…and that is pretty much where accuracy ends. Many official records indicate that the U.S. tied the second Canada team—made up of Mohawk Indians—2-2, yet somehow advanced to the final.

As it turns out, that latter result is incorrect…along with much of the rest of what has been reported about lacrosse at the 1904 Olympics. As we’ll see, however, this is in keeping with the rather shambolic nature of the 1904 Games themselves.

Meet me in St. Louis

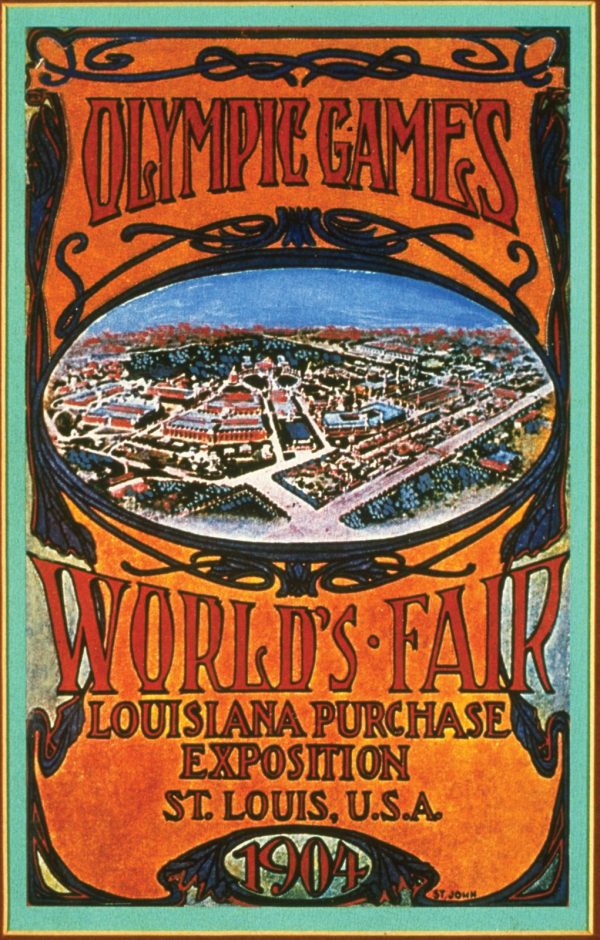

The modern Olympic Games began in 1896, and were held in Athens—the ancient home of the competition. In 1900, the Olympiad was held in Paris, which was also hosting the World’s Fair; as a result, the games ran from May through October, as sporting competitions were mixed with cultural events.

The 1904 games were slated to be held in Chicago. However, St. Louis was hosting the Louisiana Purchase Expedition—more commonly referred to at the time as the St. Louis World’s Fair—and the organizers of the expedition did not want any competition. As a result, the Expedition began scheduling its own set of athletic events to eclipse the Chicago Olympics. Ultimately, Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympic movement, stepped in and awarded the Games to St. Louis.

Many press reports did not notice, however—much of the reporting of the era focused on “world championships” being held at “the World’s Fair.” Traditional events (like track and field) tended to be considered “Olympic,” while team sports were considered part of the World’s Fair.

Given this chaos, it is understandable that historic reporting of lacrosse at the 1904 Games has been erratic, at best.

Lacrosse joins the games

Against this backdrop, it is likely that lacrosse’s inclusion in the 1904 Olympics was almost “accidental,” as it was really carried over from the schedule of events for the World’s Fair. Nevertheless, today there is no doubt that it was an official Olympic sport in 1904.

As early as January, plans were being made for lacrosse teams from across North America to participate at the Fair/Olympics. Unfortunately, international interest in the sport—and, indeed, in participating in the Games at all—was considerably dampened by the Russo-Japanese War. Ultimately, only 62 of the 651 competitors came from outside North America, and only a baker’s dozen or so countries participated.

(Lacrosse could have ended the war early, at least according to E.J.K. from Buffalo; writing a letter defending baseball to the Buffalo Evening News, Mr. K lamented the brutish nature of lacrosse, adding, “I should advise the Russians to engage a few Canadian lacrosse teams and get at the [Japanese] in the same style as I witnessed Saturday at Olympic Park [in Buffalo], and the war would be ended.”)[1]

Initially, at least, domestic interest in the lacrosse championship was high. As the host city, it was expected St. Louis would field a team, and the St. Louis Amateur Athletic Association (usually referred to as the “Triple A” club) entered the competition. In February, the St. Paul Lacrosse Club stated it would participate,[2] and, in March, it was reported that noted clubs like the Chicago Calumets, Buffalo Bisons, and Detroit A.C. and lesser teams from Boston, Pittsburgh, and Denver—along with Johns Hopkins University—had applied to participate.[3]

In the U.S., however, the Games would not be complete without the inclusion of the Crescent Athletic Club of Brooklyn. In 1893, lacrosse joined the list of sports offered by the club, and the team quickly positioned themselves in the role of missionaries for the sport. In 1897, the Crescents toured England, and upon their return took on all comers in the United States. As they usually defeated American opponents, the Crescents soon invited Canadian teams to Brooklyn. Crowds in excess of 4,000 were not uncommon for these matches.[4] In many ways, the Crescents were American lacrosse, and a tournament without their presence was unthinkable. Fortunately, in March the team’s participation was reported to be “probable.”[5]

One would have also expected a host of Canadian teams to participate, including powerhouses like Montreal Shamrocks and Toronto Lacrosse Club. However, the winter of 1903-04 found the bane of professionalism creeping into the ranks of many clubs, which summarily disqualified them from play.[6] While Montreal was still amateur, it was being dissuaded from attending by the fact that no allowance for travel or expenses was being made by the tournament organizers, and the trip was simply too expensive to make.[7] After some hemming and hawing, the Winnipeg Shamrocks announced they would make the trip to St. Louis. No other Canadian teams indicated they would attend (although a second Winnipeg team briefly considered going).[8]

“Olympic lacrosse matches may not result in a fizzle”

A lot of the initial interest in the competition quickly dissipated as a result of an utter lack of organization on the part of Olympic officials. Although the Olympic matches were slated for July 5 through 7, as late as June 25 there was no set list of teams to compete.

At that point, the Crescents began to balk about attending. “Olympic lacrosse matches may result in a fizzle” was an excuse offered, but it appears the Brooklyn team was looking for reasons not to attend.[9]

Specifically, it was revealed that the Crescents were the one team insisting that organizers not pay the travel expenses of the Canadian teams.[10] The Brooklyn team was afraid that anything less than a gold medal would threaten its prestige as “America’s Team”; a recent series of losses to Toronto University and the famed Orillias team left them fearful of having to face other Canadian teams, the Minto Cup champion Montreal Shamrocks, in particular, so the Brooklyn club decided any means to discourage these teams from competing would help the Crescents cause.

When rumors of the chicanery broke, other Canadian teams—again, only one of whom had actually committed to attending the Games—insisted that Brooklyn be barred from the competition. Another piece of evidence was offered—having played the now-professional teams of Fergus and Orillias in the months leading up to the event, the Crescents themselves were deemed “tainted.”[11] Whether the Crescents jumped or were pushed remains an open question, but this much is clear: they did not participate in the Olympics–although, even then, event organizers were not made aware of the fact until the very last minute.

Neither did anyone else. While Triple A would play—after all, it was already in St. Louis and had nothing better to do—none of the other American teams committed to traveling to the Fair. Winnipeg finally committed to attending on June 26, and began its trip to the States on July 1. Ironically, it would play a number of American teams who had bailed on the competition on the way. On July 3, the Shamrocks tied St. Paul, 6-6, before 2,500 in St. Paul, and the Winnipeg team defeated Chicago Calumets a day later, 14-5.

Still, a two-team competition would be rather anticlimactic.

Enter the Indians…or were they already there?

And here is where things get really muddled…

Apparently, completely independent of the Olympics, a team of Mohawk Indians had been permanently encamped at the World’s Fair, playing lacrosse games as part of a demonstration of “indigenous sport.” Other tribes participating included the Cayuga and Iroquois.

While hyping a game between the Mohawks and Calumets, a Chicago paper indicated that the Indians “have been playing during the entire season at the St. Louis World’s Fair, with remarkable success.”[12] However, it appears this “season” consisted of a series of games against Triple A.

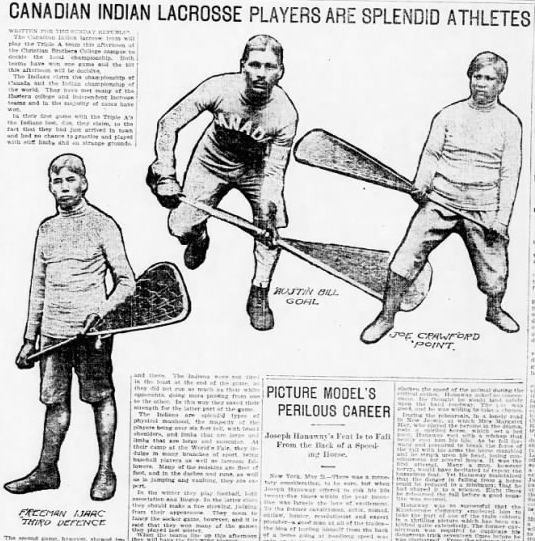

For the record, the Calumets thumped the Mohawks on July 2, 10-4. It is from this press report that the colorful tribal names reported by Bill Mallon in his The 1904 Olympic Games: Results for All Competitors in All Events, with Commentary were gleaned. As it is, these athletes also had Christian names, which were reported in the games against Triple A.

By all accounts, the Olympic lacrosse competition was scheduled for July 5 through 7. However, the Mohawks were supposed to play a 5-game series with Triple A to decide what was described in St. Louis newspapers as the “local lacrosse championship,” starting in May.[13] So was the Mohawk team in a local St. Louis league, given this turn of phrase and the Chicago paper’s reference to playing an “entire season”? Or was the “local championship” simply a reference to the series of games being played as part of the World’s Fair…but not the Olympics?

Adding to the confusion is the fact the team is occasionally referred to as Iroquois, although it is clear the team playing in this series are Mohawks.

Triple A defeated the Mohawks on May 8 (no score is available). The Mohawks defeated the St. Louis side a week later, 5-2. On June 26, St. Louis defeated the Indians, 4-0, in what was reported as the fourth game of the series, with each team having won two games (it is not clear when the third game was played). Is this the source of the “2-2” score line in the Mallon book (in that no fifth game was ever played)?

Of course, a week later—with the “official” Olympic competition days away—the Mohawks left town to play the Calumets of Chicago. This is not what one would expect from a team participating in the Olympics. Given the utter absence of any reference to a Mohawk team in the months leading up to the tournament, the fact it was playing in St. Louis as part of a World’s Fair “demonstration,” and the fact it left town prior to the actual Olympic competition (one, it should be recalled, that was starved for teams), there really is a question whether the Mohawks were an Olympic team at all, which means the ex post facto awarding the team a bronze medal would be in error. In fact, as late as 1984 the Canadian Olympic Association was questioning whether a medal had actually been awarded: “We tried four sources, and no one came up with any medalists.”[14]

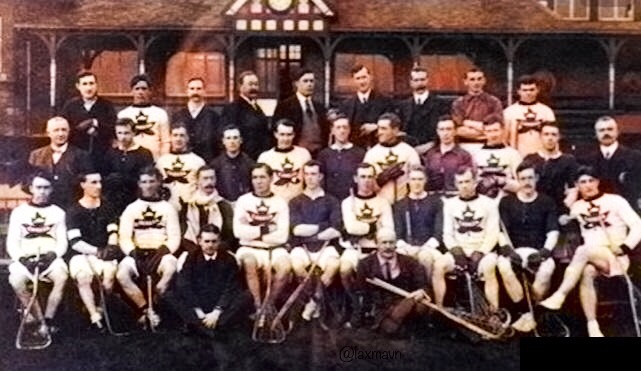

On the other hand, as the team was in St. Louis, and did play one of the competing teams, it can be fairly stated the medal was earned. In addition, there are pictures of the team wearing “Canada” jerseys, which would also indicate that the team was there as part of the international competition.

Ultimately, over 100 years later, the confusion should be chalked up to the chaos surrounding the Games.

The Final

On July 7, the Winnipeg Shamrocks defeated Triple A, 8-2, at Francis Field. “The most noticeable weak point of the locals was the fact of their being slow to pick up the ball off the ground,” wrote a St. Louis Republic scribe. “This the Shamrocks could do with the greatest ease and would scoop up the ball while going at full speed.”[15]

While for months it was reported that the Olympic lacrosse competition would run from July 4 to 7, it appears this was not originally intended to be a one-game final. Game reports indicate that the final was to be best-of-three, with the second game set for July 8. In keeping with the chaotic nature of the lacrosse tournament, however, this was quickly abandoned—presumably, the St. Louis team knew they were completely outclassed by the Canadians and felt enough was enough, although contemporary reports also lament the awful condition of the field as a reason. Winnipeg left town as “world champions.”

Once again, the official record gets confusing. Canadian newspapers report that the Shamrocks defeated Triple A 6-1 in one game, and then defeated “St. Louis” in the final, 8-2.[16] Of course, as Triple A and St. Louis are one-and-the-same, and there is no evidence of anything other than a one-game final, the first game appears to be a myth (indeed, Winnipeg papers make it clear the 8-2 result was against Triple A). A Manitoba sports history site suggests the 6-1 game was against the Mohawks[17]–and, in fact, a headline in a Vancouver newspaper suggests this was the case. However, the article itself states it was the St. Louis (Triple A) team that defeated the Mohawks, not Winnipeg.[18]

Interestingly, reports also suggest that Winnipeg was to play the Crescents in a semi-final, but that the Crescents simply did not show up.[19] Again, all part of the utter chaos surrounding the event.

When all is said and done, it appears “Olympic lacrosse” in 1904 amounted to a single game. Given the matches Winnipeg played against St. Paul and the Calumets on the way to the Fair, along with the “series” between Triple A and the Mohawks, it is clear a rather entertaining tournament was possible, but for the disorganization of the event organizers and (allegedly) the underhandedness of Crescents A.C. Instead, the event was a dud. Lacrosse would return in 1908 in London–and be similarly underrepresented–and has not returned as an official sport since.

The Mohawks again

As noted, the Mallon book references the “wonderful Indian names” gracing the Bronze medal winners. And it is true—these names are wonderfully evocative, bringing to mind a Western frontier that was still wild a mere 25 years earlier.

As little is known about the team otherwise, I have decided to add the Christian names that appeared in game reports from St. Louis.[20] I will line the Indian names and Christian names side-by-side, based on the positions played. While there is no guarantee that the names are actual matches, it is hoped this information will help other researches trying to learn more about the first Olympic lacrosse bronze medal winners.

| TRIBAL NAME | Position | CHRISTIAN NAME |

| Black Hawk | G | Joe Crawford |

| Black Eagle | P | Austin Bill |

| Almighty Voice | C.P. | Jacob Jamison |

| Flat Iron | 1st D | Eli Henry |

| Spotted Tail | 2nd D | Amos Abida |

| Half Moon | 3rd D | Freeman Isaac |

| Lightfoot | C | Beerman Shoro |

| Snake Easter | 1st H | Frank Seneca |

| Red Jacket | 2nd H | Sandy Turkey |

| Night Hawk | 3rd H | Eli Martin |

| Rain In Face | OH | Joe Clark |

| Man Afraid Soap | IH | Philip Jackson |

(At the same time as this list was compiled for an earlier

article, a similar effort was published by Hilary Evans at OlympStats.com. According to Evans, research by Swedish

athletics historian Tomas Magnusson has revealed that “Man Afraid Soap” (also

reported as “Man Afraid of the Soap”) was Freeman Joseph Isaacs, father of

Canadian Lacrosse Hall of Fame inductee Bill Isaacs.[21] The remainder of the names are the same as

reported above.)

[1] Buffalo Evening News, July 5, 1904

[2] St. Paul Globe, February 20, 1904; Winnipeg Tribune, February 23, 1904

[3] Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 20, 1904. Apparently, there were also tentative plans for a team from England to also participate in the Games; however, the team decided to postpone its trip to the United States until the following summer.

[4] Fisher, Donald M., Lacrosse: A History of the Game (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), pp. 75-81

[5] see note 3

[6] see generally Winnipeg Tribune, April 18, 1904

[7] Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 23, 1904

[8] Winnipeg Tribune, May 28, 1904

[9] Brooklyn Life, June 25, 1904

[10] St. Paul Globe, June 23, 1904

[11] Id.

[12] Chicago Inter Ocean, July 2, 1904

[13] St. Louis Republic, May 15, 1904

[14] Cleary, Martin, “If Morris makes it to medal he’ll salute Indian heritage,” Ottawa Citizen, August 9, 1984

[15] St. Louis Republic, July 8, 1904

[16] see Hawthorn, Tom, “Shamrocks were golden 100 years ago today,” The Globe and Mail, July 7, 2004

[17] see http://honouredmembers.sportmanitoba.ca/inductee.php?id=304(retrieved October 30, 2018)

[18] Vancouver Daily World, July 16, 1904

[19] Manitoba Morning Free Press, July 8, 1904

[20] St. Louis Republic, May 16, 1904

[21] http://olympstats.com/2018/05/07/the-truth-behind-man-afraid-of-soap/ (retrieved October 30, 2018)