Players’ passion is the fuel for Major Indoor Lacrosse League

By BRAD HERZOG Journal Staff

The game is part field lacrosse, part hockey. The team nicknames are part USFL, part American Gladiators. The players are part- time.

But the Major Indoor Lacrosse League is full of excitement this week. It is, after all, championship weekend. Or didn’t you know?

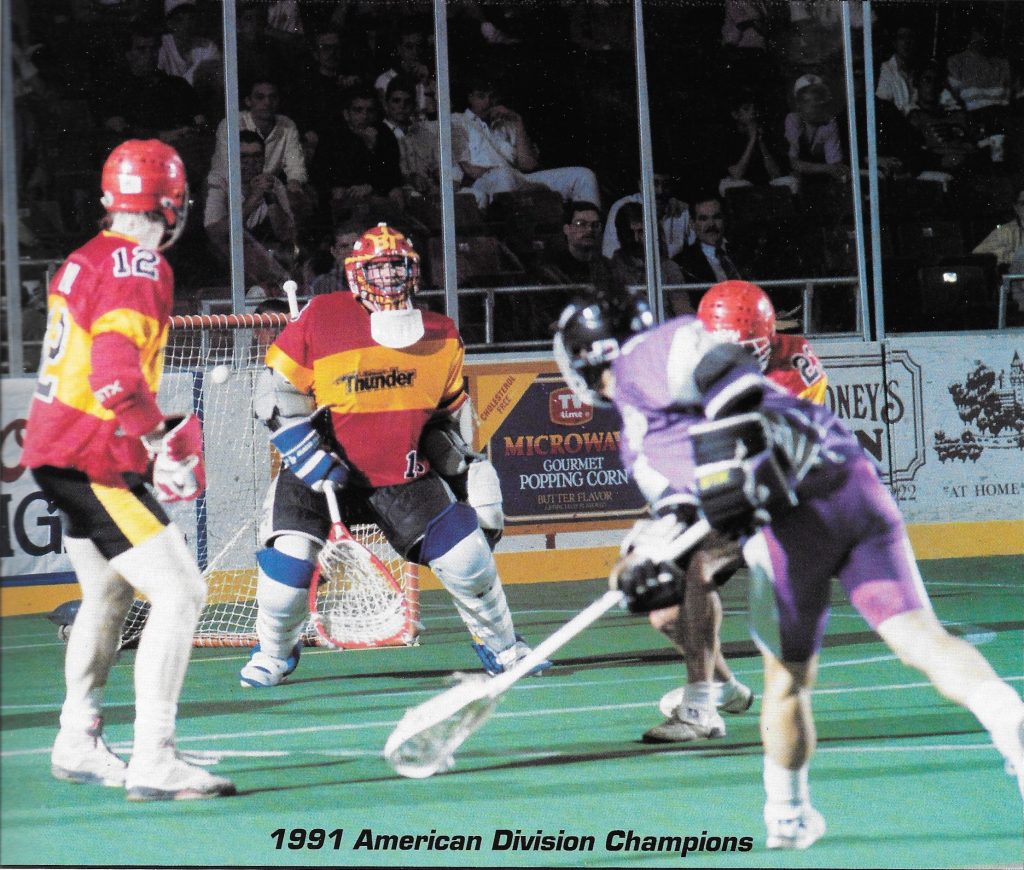

The Detroit Turbos, winners of the National Division, will meet the Baltimore Thunder, champs of the American Division, in the World Championship game at 8 p.m. Saturday at the Baltimore Arena.

Pretty heady stuff — considering four teams didn’t even make it to the finals.

Alright, it’s not the NFL. It may not even be the WLAF, but playing in the Major Indoor Lacrosse League are many of the best athletes in the sport. Can the World League say the same?

Indoor lacrosse has its roots in Canada and, on an amateur level, it is still primarily a Canadian summer game played in iceless hockey rinks. Today’s professional league began in the winter of 1987, as the game found its way into Northeastern American cities.

Four teams — the Baltimore Thunder, the Washington Wave, the Philadelphia Wings and the New Jersey Saints — comprised the Eagle League, which was renamed the Major Indoor Lacrosse League (MILL) one year later.

One assumes the word “Major was added because the acronym for Indoor Lacrosse League would have negative connotations.

In 1989, two more teams — the Detroit Turbos (playing in Joe Louis Arena) and the New England Blazers (playing in the Centrum in Worcester, Mass.) were added. Also that year, the New Jersey team moved to Long Island’s Nassau Coliseum, becoming the New York Saints — an oxymoron, perhaps?

Last year, the league merged the Washington and Baltimore franchises and added the Pittsburgh Bulls to the fold.

In 1991, the six teams played the league’s most expansive schedule to date. Five home and five away games per club amounted to a 30-game regular season.

Two three-team divisions were established, with the respective winners competing for the sacred North American Cup.

Hence, Saturday’s game. The Turbos versus the Thunder. The nicknames may not inspire, but the big-name players do.

The teams are a collection of American and Canadian college stars from powerhouses such as Syracuse, Hobart, Maryland, North Carolina and Virginia.

“You meet guys you’ve read about in your college days. Every guy was the star of their team,” said John Heil, one of eight former Cornell players in the MILL. “It elevates your play that much more.” Heil and former All-American Vince Angotti, both members of last year’s Big Red team, have started for Baltimore in each of the Thunder’s 10 games this season.

Six other former CU stars play for New York, including league All-Star Mike Cummings, his ( brother Bob, the Cook brothers (Ed and Kevin) and Matt Crowley. Former CU defenseman Todd Francis competes for the New England club.

In all, there are approximately 180 competitors in the MILL. Though it is a professional league, it is more of a hobby for the players, who are paid per game about what Michael Jordan makes per breath.

“It comes in handy,” Heil, a rookie, said of the nominal salary. “It gets a lot better for the veterans. They may make three or four hundred dollars a game.”

The salary scale is indeed based on seniority, with players receiving anywhere from $150 to $350 per game, plus travel expenses that amount to about $50 per contest.

The competitors do receive some benefits. For example, they fly to every game and stay in first-class hotels. But that is the extent of it — with two notable exceptions.

Lacrosse living legends Paul and Gary Gait, who led Syracuse to three straight national titles, are rookies on the Detroit Turbos and the league’s top players.

Though the Gaits receive rookies’ salaries, they also have promotional contracts with Coors Light, a big sponsor of the MILL, and STX, a major manufacturer of lacrosse equipment.

For the rest of the league, professional lacrosse is a part-time experience. Angotti is a salesman for a pharmaceutical company. Heil is preparing for graduate school.

“Most of the people would probably play for free, but the opportunity’s there, so we gladly take it,” said Heil. “It’s a way to keep the competitive juices flowing after the college days are over.”

The league’s type of game isn’t run-of-the-mill lacrosse of the outdoor variety. Indoor or “box” lacrosse is distinctively different from its outdoor counterpart.

Heil was an attackman at Cornell. Angotti was a midfielder. Both are forwards in the indoor league. In fact, just about everyone is a forward, as a starting lineup consists of five forwards and a goaltender, with an occassional defensive or faceoff specialist thrown in.

Collegiate defensemen are less prepared than forwards for the MILL unless they have quite a bit of offensive talent. By the same token, offensive players have to be able to defend. “Everyone’s pretty much a midfielder,” Heil said. “It’s like fullcourt basketball with five shooting guards. The key to scoring is fastbreaks, running and gunning. Five- on-five offense makes it difficult to score because everyone is compressed in a very small area.”

Though there are the familiar 15-minute quarters, there is also a shot clock in indoor lacrosse. In addition, the net is smaller and the goaltender’s job is not to catch tlie ball, but to block it.

The goalies are outfitted like hockey netminders, except they wear baseball catchers’ shinguards — a good thing since they face far more shots from stronger shooters than in the college game. In fact, Baltimore goaltender Jeff Gombar set a new league single-game record with 60 saves against New York this season.

“You have to put a show on for the fans,” said Heil. “That’s what they’re there for.”

On the average, league teams played about three games a month this season, usually on Saturday nights. The average attendance at a MILL game was more than 9,300 per contest, mostly due to the Philadelphia team. The Wings averaged more than 15,500 spectators in their five games at the Philadelphia Spectrum, home of the 76ers and the Flyers. Even 76ers forward Charles Barkley found his way to a couple Wings games and became the only person to get an honorary Wings jersey.

“He appreciates what a lot of these guys do, and the fact that they don’t get paid much for it, ” said Mike French, a three-time All- American at Cornell and the National Division I Player of the Year in 1976. French played for Philadelphia in the league’s inaugural season (1987) and has been the team’s general manager since 1988. “It’s part-time. It’s a labor of love,” said French, who also heads a hospitality industry consulting services group in Philadelphia.

Fan support varies according to : the team and the arena. At 6,826 fans per game, the New England franchise drew the least support this season. Baltimore, with an average attendance of just under 9,000, was the league’s second-best draw.

“There’s a pretty big following in Baltimore because they’ve made an effort to get all the top players from the Baltimore area,” Heil said.

In general, Heil finds mixed reviews when gauging the public’s interest in the league.

“Once in a while, people will say that it’s some sort of a freak show,” he said. “But then there are other people who are so into it that they come to watch us practice.”

However, French believes the players need the game as much as the fans do.

“The Gait brothers are two of the greatest players who ever played, but they need the league because their ability to get further endorsements and to be recognized depends on them playing,” he said. “If you don’t have a place to play in lacrosse, your popularity dries up very quickly, and the fans remember the next guy.”